Saturday, January 27, 2018

Herriman Saturday

June 12 1909 -- Frank "Cap Dillon, manager of the Angels, makes his appearance in Herriman's "Guess Who" series.

What I found of curiosity value in this cartoon is that apparently even in 1909 baseball caps had those neat little circular air holes in them. Wonder when they originated? I googled "evolution of the baseball cap" and got only a bunch of half-assed links, none of which explained much of anything. So hey, you researchers out there, is there an opportunity to make a rare *new* contribution to the history of baseball here?

Labels: Herriman's LA Examiner Cartoons

Comments:

Here's a link to the Baseball Hall of Fame, and a discussion of the evolution of the baseball hat. You'll note that a 1903 advertisement for a "Philadelphia style" hat has the air holes; older ones don't seem to have them.

http://exhibits.baseballhalloffame.org/dressed_to_the_nines/caps.htm

http://exhibits.baseballhalloffame.org/dressed_to_the_nines/caps.htm

Also worthy of note: the Library of Congress has a large collection online of the Spalding Baseball Guides from 1889 on, which have advertisements for hats.

https://www.loc.gov/collections/spalding-base-ball-guides/

Post a Comment

https://www.loc.gov/collections/spalding-base-ball-guides/

Friday, January 26, 2018

Wish You Were Here, from Kin Hubbard

In 1907 the International Postcard Company issued a set of Abe Martin postcards. Hubbard's feature was only three years old at this time, running in the Indianapolis News. Unlike most of their cards, which seemed to be existing Abe Martin sayings, this one seems to be self-aware that it is a postcard.

Labels: Wish You Were Here

Thursday, January 25, 2018

King News by Moses Koenigsberg: Chapter 16 Part 1

King News by Moses Koenigsberg

Published by F.A. Stokes Company, 1941Chapter 16

Genius Rides the Lone Wolf (part 1)

link to previous installment link to next installmentIf W. R. Hearst had a Kismet—if Fate pressed upon him a gift from Pandora’s box—it was to “shuffle the cards.” He played no game for stakes. But he was an inveterate dealer of solitaire, at the most unexpected times and places. And he continued the deal throughout his waking hours. The pasteboards displaced by whatever came to hand, he ruffled his deck of chain newspapers, magazines, motion pictures, interiors of medieval castles, Gobelin tapestries, silver antiques, gold mines and other items interspersed between what grew into his major collections of $30,000,000 in curios and $40,000,000 in real estate.

Reshuffling of the cards at solitaire before the deck was exhausted betrayed the same impatience with which Hearst repeatedly shifted a policy of business operation sometimes before the current method had been fully installed. His handling of his syndicates and news services had typified the practice. Consolidation and segregation shifted back and forth over the years. In March, 1911, a series of memoranda from Hearst were pieced together by Farrelly and their gist put into this form:

My idea now ... is to sell things separately and get more money. The syndicate ought to be divided up into a morning news service, an afternoon news service and morning feature service, an afternoon feature service and a Sunday service; and then we can sell any one of these five things, or we can sell two, three or four or five of them, provided the amount paid for them is sufficient. ... I think I will divide the services in the morning field and the evening field at least and put separate people in charge of each service and let them see how much each responsible manager can get out of his particular lines of articles. I have found this to work very well with the newspapers and it might be entirely beneficial with the news services.

Before Farrelly had acknowledged these directions, Hearst wired him, “Why not give Koenigsberg the evening service and you keep the morning service?” Then, still without a reply from Farrelly, he ordered the incorporation of National News Association. To that organization was assigned the distribution of all Hearst features and telegraphic matter prepared for release to afternoon newspapers. Under Hearst’s instructions, Farrelly formally tendered to me all the books and affairs of National News Association. I persuaded him to delay the transfer.

The set-up was utterly unattractive to me. It meant a traffic in elements originating with and under the control of other Hearst lieutenants. To manage such a unit would be to violate the resolution that prompted my resignation as publisher of the Boston American—the decision never again to assume managerial responsibility to anyone except the owner. Moreover, the new project was unfeasible. It would start with a deficit much more likely to distend than diminish.

A stratagem enabled me to evade this undesirable assignment. The ruse was based on Hearst’s yearning for new links in his newspaper chain—a passion so absorbing that it frequently diverted him from other purposes. I notified him that opportunities to acquire two different dailies were maturing concurrently. Both engaged his lively attention. One was the Omaha Bee, owned by Victor Rosewater and his brother, Charles. The other was the Louisville Herald, a knot in the string of John C. Shaffer publications.

W. J. Langdon, chief auditor of the New York American, was detailed to assist me in Louisville. Harmon Campbell, head of the auditing department of the Chicago Examiner, helped me in Omaha. They supplied material enough to keep Hearst’s interest engaged for a couple of months. Finally, I advised against the purchase of either property. Prospects for the acquisition of other newspapers were meanwhile developed. In Hearst’s engrossment with these negotiations, the program to saddle me with National News Association was forgotten. It is noteworthy that Hearst did buy the Omaha Bee sixteen years later—to his great regret.

|

| W.H. Johnson |

It was decreed that International News Service—Feature Department be placed under my management in conjunction with Newspaper Feature Service and King Features Syndicate. Bradford Merrill was instructed to work out the arrangement. Following Carvalho’s resignation, Merrill’s letterheads bore the legend, “Office of the general manager of the Hearst newspapers.” This designation was recognized by all except Arthur Brisbane. He ignored it. But friction was not visible to the naked eye because Brisbane confined his working duties to the evening papers, which Merrill skillfully sidestepped.

Merrill relayed to me Hearst’s request that I take over the syndication of all his newspaper features. My first response was a question. What would happen to the outgoing manager? More than twenty years of observation had left me with an abundant wariness about superseding a Hearst executive. Merrill assured me that a satisfactory place would be provided for Johnson. It would be entirely apart from the syndicates. That, I told Merrill, was one of two conditions prerequisite to consideration of the proffered job. The other proviso was complete independence from anyone save Hearst himself. “That’s exactly what Mr. Hearst wants,” he answered.

Within a week word came from Hearst advising that Johnson be retained in the syndicate. The message was delivered by Julian Gerard. Brother of J. W. Gerard, who was recalled as United States Ambassador to Berlin at the outbreak of hostilities with Germany, Julian was one of the most likable lambs ever jostled in the Hearst fold. He sat at the desk that Carvalho had vacated. He never found the sitting comfortable. His chat with me resulted in this letter:

April 30 1918

Dear Mr. Hearst:

It has been my understanding that you desired to consolidate the operations of your syndicate enterprises, first, to reduce expenses and, second, to increase revenues.

Except as to the retention of those artists and writers whose work you reserve for the exclusive use of your own papers, I have assumed that the syndicate management would have a free hand to effect economies and to expand sales. Mr. Gerard apprises me of your desire to appoint an expensive sales manager.

Such an appointment would preclude the programme of economy I have worked out. It also would impair seriously my freedom of action in prosecuting my own selling plans and would thus impede my efforts to increase revenue.

Mr. Gerard has mentioned the name of a man who has been in control of one of your syndicates. I submit that his appointment to an important position in the consolidated syndicate might hamper revisions of selling methods.

If Mr. Gerard understands correctly your wishes in this matter, I must assume that you have altered your intention to charge me with responsibility for your syndicate operations. If, however, Mr. Gerard has misapprehended your desire in this respect, I am prepared immediately to take personal charge of all your syndicates.

Faithfully, M. Koenigsberg

Hearst received this memorandum in Chicago. He telegraphed his financial manager, Joseph A. Moore, one of my close friends, to “bring Koenigsberg into line.” But the understanding with Merrill having been broken, there was no valid reason to alter my resolution at Moore’s urging. Hearst’s insistence on what was to me a most unwelcome condition had made the proffered job unattractive. If he had revised his decision to detach Johnson from the syndicate, why make any change? Why not keep Johnson on as general manager?

Moore, after transmitting this advice, blamed me for putting him “in bad with the chief.” On a plea of friendship, he persuaded me to accompany him west for another talk with Hearst. It has been impossible to find anything but self-reproach for the weakness of capitulating under their joint suasion. But this humiliation was poulticed by amusement over the sequel.

Johnson never officiated as sales manager. A month was to ensue before his induction into the position. It was agreed that he take that time for a vacation. He had been gone three days when a snarl in the syndicate’s records made it necessary to summon him to the office for a conference. It was not an amiable session. Johnson chose to be bitterly contumacious. At the end of an hour we reached an abrupt impasse. Johnson had raised a couple of points about which it might be prudent to consult counsel. Interrupting the argument for that purpose, I telephoned from an adjacent room to Louis B. Eppstein. He was attorney for King Features Syndicate. He was also one of my cronies.

My first query was: “What, if any, liability devolves on a corporation when its general manager uses violence to eject a subordinate from its headquarters?” The choking sound that delayed Eppstein’s reply might have been either a gasp of sympathy or a healthy snicker. “If the man is annoying you and he refuses to leave peaceably,” Eppstein said with the unctuous tone of a patient instructor in etiquette, “you may employ such force as is necessary to expel him from the premises.”

Johnson relieved me of the need for pursuing this advice. On the way to the elevator, he shouted, “I resign as of May first.” That was the date fixed for the end of his vacation. During the next ten years, Johnson was my competitor as manager successively of the World Color Printing Company of St. Louis, the New York Tribune syndicate and Editors’ Feature Service. Afterward, he became publisher of the Tucson Citizen. Then he sought me out to extend assurances of his friendliness.

|

| Marion Davies |

We were getting up to leave when Hearst said to me, “I understand you stage boxing bouts at your office every afternoon at five o’clock. Why haven’t you invited me?”

The fact that Hearst had learned of the scuffle with Johnson was more disconcerting than his banter. He found a keen relish in my confusion. He was too much amused to listen to my explanation. No other reference passed between us concerning the defeat of a program to which he had given considerable of his own time, beside the recurrent attention of his general manager, Bradford Merrill, his business manager, Julian Gerard, and his financial manager, Joseph A. Moore, to say nothing of the waste of my energies. And it is my guess that Hearst got more fun than vexation out of the episode.

Assuming management of the consolidated syndicates meant straddling the divide along which the Hearst organization writhed in internal conflict. On the one hand was the agency responsible for the acquisition and development of features for the whole chain of morning, afternoon and Sunday publications. On the other hand were the newspapers fuming over arbitrary assessments for copyrighted materials in the selection of which they had no voice. Some of them suspected that the rates were disproportionate. Their suspicions were well grounded. Hearst, himself, fixed the levies. They were not based on the value of the service delivered. They were scaled according to ability to pay. This was in harmony with the policy of an institution in which logic gave way to expedience.

Under such a regimen, friction was unavoidable. Its persistence was the subject of an elaborate analysis by Bradford Merrill eight years after the syndicates were placed under my management. Copies were transmitted to all the publishers and editors in the Hearst organization. They were accompanied by an identical note from H. O. Hunter, secretary to W. R. Hearst, under date of July 12, 1927. Hunter relayed a sharp comment from his chief. It pointed out Mr. Hearst’s feeling that his “newspaper folk” did not appreciate what they were getting. Merrill translated his report into an institutional lecture, which he delivered, with variations, as a “get-together” exhortation at several meetings of Hearst executives.

“The feeling prevalent among our editors that our features cost our papers more than the features they buy from outside syndicates,” he said, on one occasion, “has no basis in truth. Lists have been supplied showing the estimated value—the assessment—for every item furnished to each of our newspapers. Comparison with what they pay to outside syndicates is therefore easy. Every editor should be instructed to make this comparison. The proof will be before him that our own most conspicuously displayed and most popular features cost our papers from 60 to 70 percent of the price that they are actually paying to outside syndicates for less valuable features.

“Competition among the syndicates is intense and destructive. Very few are making any profit. Changes of managers are of almost daily occurrence in consequence. [E. H.] Harriman’s daughter [Mrs. Rumsey] has already sunk $300,000 in backing the [W. H.] Johnson syndicate, still losing money and hopeless. The management of our syndicate is the only one in the United States that has not been changed in the last eight years.

“The gross income of our combined syndicate services has increased nearly threefold. While the Hearst papers formerly paid more than half the whole operating cost, now they pay only $2,100,000 out of a gross revenue of approximately $6,000,000.”

It is pertinent here to recall that in the year prior to my assumption of control, International News Service—Feature Department suffered a loss of approximately $79,000. On May 17, 1918, it was separately incorporated as International Feature Service, Inc. It came under my management as of July 1, 1918. There were no deficits after that date.

A highly practical consideration led to the premiership of King Features Syndicate in the Hearst syndicate line-up. Its name was less objectionable to a large number of prospective clients than the title of International Feature Service. The word “International” was a Hearst label. It stirred antipathies engendered by apprehension. As told earlier in these pages, scores of publishers lived in dread of an invasion of their fields by the Hearst colossus. That fear was kept alive by a definite threat. It was a clause, inserted at Hearst’s insistence, in every contract under which features were supplied to any community with more than 75,000 population. It provided that “this agreement may be canceled on six months’ notice in the event that W. R. Hearst decides to acquire or establish a newspaper in the city above mentioned.”

That stipulation—never enforced—became an empty gesture that cost Hearst millions of dollars during the ten years of my administration. This huge fortune could have been added to the syndicate income without a penny of increased expense. It would have been readily forthcoming under long-term commitments. Many publishers were eager to obtain, at handsome rates, the advantages that would be embraced in a five or a ten year deal with the Hearst organization. They would be fulfilling a twofold desideratum. First, they would be buying insurance against the menace of a hazardous competition. Second, they would be enabled to stabilize their feature budgets.

This disposition was strikingly illustrated by the largest newspaper syndicate contract ever executed. It was the only case in which Hearst consented to omission of his six months’ cancelation clause. It covered an initial period of ten years, beginning in 1922. A minimum consideration of $1,940,200 was provided— a $50,000 cash bonus, plus weekly payments of $3,635. The contracting parties were King Features Syndicate and the Pittsburgh Press. Oliver S. Hershman was the owner of the Pittsburgh Press. He took no part in the transaction. He was represented throughout the negotiations with me by Harry M. Bitner, his managing editor. Shortly thereafter, Bitner signed another indenture at my desk. It enrolled him in the Hearst personnel, to the top of which he rose some years later as general manager of the newspaper organization.

The syndicate crops that Hearst forbade me to reap would have brought enough at least to temper if not to avert altogether the lean days upon which he afterward fell. Several sources of income persistently rejected at my hands have since yielded large sums regularly. One, by no means the most extensive, may be described as by-product. It consists of royalties for commercial uses of copyrighted characters and their titles. Hearst spurned the idea. “That’s chickadee stuff,” he said. “Please don’t let it take up any of your time.” A department to handle this business was set up by a succeeding management. It grossed $400,000 in one year. If that be “chickadee stuff,” it’s rather high priced.

Hearst steadfastly opposed personal capitalization “on the outside” of popularity achieved through newspaper features. He felt “the sideline might block the mainline” of attention of the artist or writer. It did grow into the chief source of income of one of the most conspicuous members of the Hearst staff, Walter Winchell. That was after my retirement from the organization. Winchell was never on my payroll. His emoluments for broadcasting greatly exceeded his newspaper salary.

The syndication of Winchell’s column turns a revealing light on the potency exercised by features among publishers. Eagerness to acquire a circulation-maker may brush aside constraints of business caution. Winched boasted of such an instance. It was the provision in his syndicate contract ostensibly holding him harmless from judgments for libel. Of course, such a stipulation would be unenforceable. It would be adjudged against public policy. But, as a formal condition attending the publication of his articles, it furnished an illuminating commentary on a significant phase of journalism.

|

| Will Rogers |

“Bugs” Baer had written at least two paragraphs of exactly the same purport, but the crispness of Rogers’ line caught my imagination. The next day at the Friars Club, of which we were fellow members, I proposed to Rogers that he supply a batch of witticisms for syndication as a daily newspaper feature. The idea startled him. He was not sure of its feasibility. We discussed the thought at several subsequent meetings. At last, on the pretext of ironing out some remaining details in his own mind, he asked for time to make a decision. We clasped hands on his pledge to notify me as soon as he was ready to start his career as a journalist.

When Rogers’ comments began to appear in the New York Times, my annoyance was too great to be suppressed. I took him to task. It is one of my abiding regrets that our difference was not composed before he passed away. Will never gave the reason for breaking his promise. The truth reached me through a mutual friend. Rogers had been persuaded that it would “be better to range as a lone wolf than to run with a pack.” That was the argument with which the McNaught Syndicate won his adherence.

In the New York Times Rogers was the only humorous columnist. In the Hearst papers he would have been one of many— a minstrel in an olio, surrounded by such favorites as “Bugs” Baer, “K. C. B.” (Kenneth C. Beaton), J. P. Medbury, Ted Cook, W. F. Kirk, Harry Hershfield, George E. Phair and J. J. Mundy. It didn’t matter whether he might outclass any or all of them. He would still belong to a chorus. Will Rogers preferred the role of a prima donna without a supporting cast.

Labels: King News

Wednesday, January 24, 2018

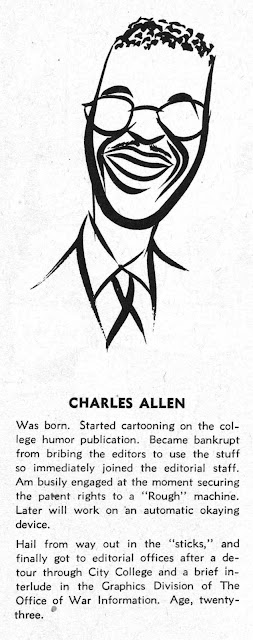

Ink-Slinger Profiles by Alex Jay: Charles Allen

1965

A “Charles E. Allen”, of Americus, Georgia and sixteen months old, was found in the 1920 U.S. Federal Census. I believe he was the cartoonist although the discrepancy of birth years cannot be explained at this time. Allen was the youngest of nine children born to Will, a carpenter, and Irene, a servant. The family lived at 1002 Magnolia Street.

According to the 1930 census, Allen’s oldest brother, Lee, was head of the household that included three siblings and their mother, a widow. They resided in Americus at 617 Dismuke Street.

Sometime before 1935, the Allen family moved to New York City. The 1940 census said Allen’s sister, Georgie, was the head of the household that included the youngest brother, Agustabus, and mother. The family of four lived at 212–14 West 111 Street. Allen’s education included three years of high school and some college.

Who’s Who said Allen attended the College of the City of New York and was awarded a prize in 1941.

Best Cartoons of the Year 1944 printed Allen’s self-portrait, cartoon and profile (above).

Allen provided addition information about himself in Best Cartoons of the Year 1947.

Allen should not be confused with Colin Allen who drew What a Family that ran from 1946 to 1954.

Who’s Who said Allen contributed to Collier’s, Liberty, This Week and other magazines, and was a member of the Artists Guild and the American Society of Magazine Cartoonists.

Beginning in 1955, Allen was the cartooning instructor at the School of Industrial Art in Manhattan, New York City. The school was renamed the High School of Art and Design in 1960. Two of Allen’s colleagues were Alvin Hollingsworth and Bernard Krigstein, and his students included Ralph Bakshi (1956), Neal Adams (1959) and Art Spiegelman (1965). Allen’s last year at the school was 1968.

According to Who’s Who, Allen resided, in 1953, at 363 Grand Avenue in Brooklyn. A record at Ancestry.com had another address for Allen, “3368 21st St, Astoria, NY, 11106-4273”.

At some point Allen moved to California. He passed away June 8, 1999 and his last residence was San Ysidro, California.

American Newspaper Comics (2012) said Allen drew Tan Topics for Continental Features. The panel began in the Atlanta World on August 23, 1943 and ran for several years. Later the panel continued with Claude Newkirk in the 1950s into the 1970s. In Pioneering Cartoonists of Color (2016), Tim Jackson wrote:

Tan Topics was drawn in brush and ink by Charles Allen (?–?) as a single-panel gag comic. Continental Features distributed Tan Topics nationally during the early 1940s.

The subject matter reflected topics of the day, such as the meat shortages of World War II America and the changing tastes in fashions. Allen’s artistic style improved as the comic preceded. The artist became more daring, adding detailed background scenes, although his ability to draw shapely, pinup-style women generally still left much to be desired.

Allen should not be confused with Colin Allen who drew What a Family that ran from 1946 to 1954.

Who’s Who said Allen contributed to Collier’s, Liberty, This Week and other magazines, and was a member of the Artists Guild and the American Society of Magazine Cartoonists.

According to Who’s Who, Allen resided, in 1953, at 363 Grand Avenue in Brooklyn. A record at Ancestry.com had another address for Allen, “3368 21st St, Astoria, NY, 11106-4273”.

At some point Allen moved to California. He passed away June 8, 1999 and his last residence was San Ysidro, California.

—Alex Jay

Labels: Ink-Slinger Profiles

Comments:

This was Mr Charles Allen's cartooning class. He was a great teacher and a great person. He used to always yell at me when I came to class. "Albert! You back again!" He was great! I see hear that he passed away in 1999. So sorry. He had a great cartoon every Saturday in a paper, unfortunately, I forgot the name.

BTW, the boy up front in the white shirt is James Flanigan, a friend,

I am sitting in the back behind Mr. Allen, also in a white shirt and tie. That's how we dressed then.

Post a Comment

BTW, the boy up front in the white shirt is James Flanigan, a friend,

I am sitting in the back behind Mr. Allen, also in a white shirt and tie. That's how we dressed then.

Tuesday, January 23, 2018

Ink-Slinger Profiles by Alex Jay: Colin Allen

|

| 1932 |

In the 1920 U.S. Federal Census, Allen was the oldest of two brothers. Their mother was a widow. They and three roomers lived in San Francisco, California at 1665 Hayes Street.

In 1930 Allen lived at the Masonic Home for Children in Covina, Los Angeles County, California. Artists in California, 1786–1940 (1989) said, “While a student at Covina High School, Allen studied art under Esther Dana and won prizes for his posters and other work.” Allen contributed art to the school’s 1929 yearbook, The Cardinal.

In December 1932, Allen was in Honolulu, Hawaii where he filled out an application for a Seaman’s Protection Certificate. He was 20 years old and described as five feet ten-and-a-half inches, 155 pounds with blue eyes and red hair. Earlier Allen worked as a deck boy on the ship Maunalei from July 13 to August 1, 1932.

Allen was listed on the J.L. Luckenbach vessel crew list. The ship sailed from Los Angeles and arrived at the port of New York City on October 14, 1933. In February 1934, Allen was at the port of Havana, Cuba. In March 1934, Allen sailed from Mazatlan, Mexico to New York City.

From 1935 to 1946, Who’s Who said Allen studied at the Art Students League and Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. He produced magazine and newspaper cartoons and illustrations for the New York Times, the New Yorker, Saturday Evening Post, and others. Allen’s cartoons were published in Judge. Popular Science, June 1948, reprinted one of Allen’s Collier’s cartoons.

Allen’s art appeared in advertisements for General Electric, Gulf Oil, Standard Oil, General Mills, Ciba, Sharpe & Dohme Pharmaceuticals, and others.

The Daily Worker (New York, New York), November 28, 1938, reported the contributions of several artists to a new club, “That new night club scheduled to open within three weeks has all of us excited. Called ‘Cafe Society,’ it will kid the long drawers off its namesake and feature murals by Gropper, Hoff, Colin Allen, Earl Kerkam and others.” Colin talked about the nightclub in Cafe Society: The Wrong Place for the Right People (2009).

Allen’s cartoons were included in Best Cartoons of the Year 1943 and 1944 (below), Laugh It Off (1944) and Funny Business (1945).

Allen was listed on the J.L. Luckenbach vessel crew list. The ship sailed from Los Angeles and arrived at the port of New York City on October 14, 1933. In February 1934, Allen was at the port of Havana, Cuba. In March 1934, Allen sailed from Mazatlan, Mexico to New York City.

From 1935 to 1946, Who’s Who said Allen studied at the Art Students League and Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. He produced magazine and newspaper cartoons and illustrations for the New York Times, the New Yorker, Saturday Evening Post, and others. Allen’s cartoons were published in Judge. Popular Science, June 1948, reprinted one of Allen’s Collier’s cartoons.

Allen’s art appeared in advertisements for General Electric, Gulf Oil, Standard Oil, General Mills, Ciba, Sharpe & Dohme Pharmaceuticals, and others.

The Daily Worker (New York, New York), November 28, 1938, reported the contributions of several artists to a new club, “That new night club scheduled to open within three weeks has all of us excited. Called ‘Cafe Society,’ it will kid the long drawers off its namesake and feature murals by Gropper, Hoff, Colin Allen, Earl Kerkam and others.” Colin talked about the nightclub in Cafe Society: The Wrong Place for the Right People (2009).

Allen’s cartoons were included in Best Cartoons of the Year 1943 and 1944 (below), Laugh It Off (1944) and Funny Business (1945).

Encyclopedia of Television Shows, 1925 through 2010 (2012) said Allen drew cartoons in the TV pilot of Draw Me Another, December 21, 1945.

According to American Newspaper Comics, Allen was one of several cartoonists who drew cartoons for Wheaties cereal from 1944 to 1946. Allen produced What a Family* from September 8, 1946 to October 9, 1954. A 1950 issue of the Queens Ledger (Maspeth, New York) said “…Jim Clark, who is spending the winter at Jensen Beach with the comic artist, Colin Allen, with whom he collaborates in producing the full page comic, ‘What A Family,’ which appears on Saturdays in Hearst papers throughout the nation.” Who’s Who said Allen supplied illustrations to Pictorial Review. What a Family and Pictorial Review were handled by King Features Syndicate.

According to American Newspaper Comics, Allen was one of several cartoonists who drew cartoons for Wheaties cereal from 1944 to 1946. Allen produced What a Family* from September 8, 1946 to October 9, 1954. A 1950 issue of the Queens Ledger (Maspeth, New York) said “…Jim Clark, who is spending the winter at Jensen Beach with the comic artist, Colin Allen, with whom he collaborates in producing the full page comic, ‘What A Family,’ which appears on Saturdays in Hearst papers throughout the nation.” Who’s Who said Allen supplied illustrations to Pictorial Review. What a Family and Pictorial Review were handled by King Features Syndicate.

Who’s Who said Allen did experimental work in plastic, metal, wood and photography, from 1954 to 1958.

The Palm Beach Post (Florida), July 30, 1955, reported Allen’s return.

Colin Allen, cartoonist creator of “Whata Family,” has returned to his Stuart home for the summer months.Who’s Who said his address, in 1959, was 115 Edmondson Street in Sarasota, Florida. TedKey.com said, “…In the 1960s, Key also did a two-page cartoon chronicling the adventures of a brother and sister named Diz and Liz for Jack and Jill, a children’s magazine…. A compilation of those cartoons was published by Wonder Books, as was a Diz and Liz book written by Key and illustrated by cartoonist Colin Allen.”

He and his wife are announcing the birth of their first son, John, at Sarasota Memorial Hospital. They have three small daughters who provide many plots for his comic strip. He will return to Sarasota Sunday for the christening ceremony.

The Allen family, of Towaco, N.J., in 1949 purchased the St. Lucie Blvd. home and studio of cartoonist Zack Mosley after the Mosleys moved into new quarters on the riverfront in St. Lucie Estates. A year ago they moved to Sarasota due to his difficulty in finding part-time studio help here. The Ringling Art School at Sarasota answered his problem, he said. He also draws illustrations for E.V. Darling’s “On the Side,” and for other columnists. He said he plans to work here while supervising redecorating of their home here in preparation for its sale. The family will join him later.

At some point, Allen moved to Michigan where he lived in Detroit and Grand Rapids.

Allen drew the cover of the May/June 1986 issue of The Michigan Alumnus.

The Directory of Michigan Artists (2001) included Allen and said, in part, “Mr. Allen is now afflicted with Macular Degeneration and is legally blind.”

Allen passed away May 16, 2002, in Detroit, Michigan.

* Rebel Visions: The Underground Comix Revolution, 1963–1975 (2002) included Art Spiegelman’s assessment of Allen and What a Family.

During his senior year at High School of Art & Design, Spiegelman [Class of 1965] also became dissatisfied with his instructors. “I used to get really pissed off at my cartooning teacher Colin Allen, a real second-rate cartoonist who had done Lord What a Family, which was a third-rate version of Ride Around Town with Myrtle, which was a fourth-rate version of a Jimmy Hatlo panel. He had done this thing for a living and had done a bit of animation before becoming a high school teacher, and it was frustrating not being able to talk about cartoonists with him because he didn’t know any of the names I was referring to. I was passionate about comics and I felt his lack of interest made him so completely inadequate as a cartoonist and as a person that it was pointless to be in his classroom.Actually the cartooning instructor was Charles Allen, an African American who drew the panel Tan Topics. He was at the school from 1955 to 1968. The school was originally known as the School of Industrial Art. Charles Allen was in Who’s Who of American Art (1953) and there was no mention of What a Family. American Newspaper Comics said the names of cartoonists Jim Clark, Dewey Clark and BIP appeared in the strip from 1946 to 1949. It’s not known if Colin Allen, who had moved to Florida and then Michigan, was a guest instructor at the school. Class of 1959 graduate, Neal Adams, thought Charles Allen might have drawn What a Family.

—Alex Jay

Labels: Ink-Slinger Profiles

Comments:

Colin Allen wrote and illustrated "What A Family'.

Occasionally he hired people to help him come up with 'gags' for the 'strip'.

Charles Allen was one of those people - he worked briefly for Colin Allen.

Charles Allen never did more that work as a gag man for a brief period of time.

He did not take over the strip when Colin Allen stopped creating it.

He came to work long after the strip was formed and left long before it ended.

Jim Clark was not a cartoonist, he was a bartender who helped Colin for a brief period.

Occasionally he hired people to help him come up with 'gags' for the 'strip'.

Charles Allen was one of those people - he worked briefly for Colin Allen.

Charles Allen never did more that work as a gag man for a brief period of time.

He did not take over the strip when Colin Allen stopped creating it.

He came to work long after the strip was formed and left long before it ended.

Jim Clark was not a cartoonist, he was a bartender who helped Colin for a brief period.

Hi Lillian --

Your explanation of the role of Jim Clark and Charles Allen on What a Family is much appreciated. Are you a family member? Any idea who "BIP" might have been?

Thanks, Allan Holtz

Your explanation of the role of Jim Clark and Charles Allen on What a Family is much appreciated. Are you a family member? Any idea who "BIP" might have been?

Thanks, Allan Holtz

Hi Allan Holtz, I'm only seeing your comments now - in 2023 - are you still out there and are you still interested in answers to your questions?

Lillian

Post a Comment

Lillian

Monday, January 22, 2018

Obscurity of the Day: What a Family!

King Features liked to have an offering available to clients in every genre of comics. When Dudley Fisher's Right Around Home, a Sunday page that showed a birdseye view of a goofy family doing wacky stuff, showed some staying power in the nation's comics sections, King trotted out their interpretation, darn close to an exact copy. Debuting on September 8 1946, it was titled What a Family! and penned by magazine gag cartoonist Colin Allen.

The Sunday-only feature was very well done, starring a family named the Looneys who took the madcap antics of Right Around Home to a more zany level. However, apparently the birds-eye view genre didn't have a need for a me-too entry. I have never seen What a Family! running anywhere except in Hearst-owned papers, and then only in their less common tabloid sections, never in the flagship Puck section. Nevertheless, King kept it running for a comparatively long time, over eight years. Near the end of the run, Allen experimented with making it a more conventional strip, and lengthened the title to The Looneys --What a Family (see bottom sample), but that did nothing to entice clients. It was put out to pasture on October 9 1954.

A footnote is that in the early years of this feature Allen sometimes shared credit. On some pages you will find lurking in an unobtrusive corner the signatures of what I assume are ghosts, gag-writers, or assistants. I've seen the names of Jim Clark, Dewey Clark and B.I.P. taking their tiny bit of the spotlight.

Also, Cole Johnson, who provided some of the above samples, believed that gag cartoonist Colin Allen and black newspaper cartoonist Charles Allen were the same person. As Alex Jay will detail in the next couple of days, they were indeed two different fellows.

Labels: Obscurities