Saturday, January 13, 2024

One-Shot Wonders: Everything Has Its Use by C.M. Payne, New York Journal, 1897

Here's an early strip by Charlie Payne, who later found long-lasting success with his strip S'Matter, Pop. Given that we have three incompatible elements here -- Chinese characters and a tropical bird in an Arctic landscape, I can't decide whether Payne is incredibly naive of geography, or if that is supposed to be part of the gag. Gotta love the beautiful lettering work on that title, though!

Thsi gag appeared in the New York Journal's comic section of March 28 1897.

Labels: One-Shot Wonders

My take on the Arcticallity and the Chinamen are not born of naiveity of place, obviously everyone knows Toucs are seen only close to the Equator, so that's just part of the disregard for logic that's part of such gags, but I think Payne probably had no idea what Esquimoux looked like, so Chinese was close enough for him.

Nice to see Payne working the big time so early on.

Friday, January 12, 2024

Ink-Slinger Profiles by Alex Jay: Martin Nadle

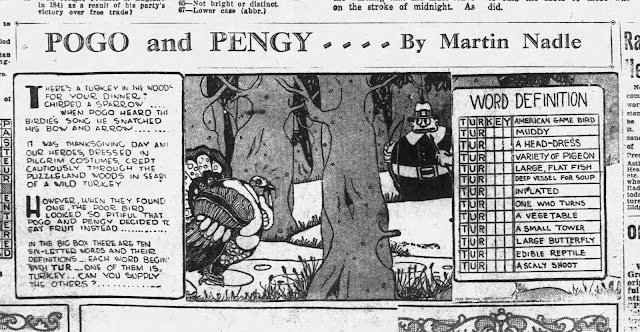

When I was 16, my puzzle panel, “Kiddies Heaven” appeared in the old New York Evening Graphic. At 19, I drew a weekly puzzle strip, “Pogo and Pengy” for King Features Syndicate, followed by “The Noodleteaser Family” for the New York Post [July to October 1943] ...

Nadle (Martin) Adventures of detective Ace King, the American Sherlock Holmes. A story in cartoons. © Oct. 6, 1933; AA 131033; Humor pub. co. 29216

This one-shot introduced one of the earliest detective characters created directly for comic books. Martin Nadle spelled his last name Naydell [sic] when he worked for DC Comics in the 1940s.

Cartoonist Nadle, who was with Publishers Service approximately three years up until May 13 of this year, formerly did art work for the New York Daily News and a weekly puzzle strip for King Features Syndicate. For a time, he was staff artist on the old New York Evening Graphic and was with that paper when it suspended.

Dell, MartinPlay Comicode and test your power of deduction. © Martin Dell; 23Dec59; A429128.

Martin Dell Starts ‘Comicode’ GameA syndicate has been formed to market a word puzzle game by a successful cartoonist and puzzle creator.The syndicate: The Martin Dell Syndicate, Inc., 310 E. 44th St., New York 17, N. Y.The puzzle: “Comicode.”The creator: Martin Dell.The starting date: Oct. 2.“In achieving the lifelong ambition of setting out on my own, which is my present status, I am honestly proud to be able to offer the exhilarating Comicode as an opening wedge for the Martin Dell Syndicate,” said Mr. Dell. “Subsequently, I intend marketing other features outside the puzzle category.In 1954, Mr. Dell created “Jumble ... That Scrambled Word Game,” and produced it for the Chicago Tribune-New York News Syndicate up to last April 20, when his contract expired, terminating a seven-year affiliation. Mr. Dell, cartoonist and puzzle maker, has been the talent behind scores of newspaper puzzle contests all over the country and his work has appeared in many top magazines. ...

Labels: Ink-Slinger Profiles

Wednesday, January 10, 2024

Toppers: Simp O'Dill

William Randolph Hearst was an enthusiastic lover of comics, and he usually had a good eye for quality. Most famously, he championed that oddball strip Krazy Kat and kept it running despite dismal sales. But everyone can have a blind spot, and to my mind Hearst's was The Nebbs. According to old stories, Hearst absolutely loved the strip, and though he did not syndicate it, insisted that many of the Hearst papers run it.

I, on the other hand, cannot see the attraction. To me it reads like a weak-kneed version of The Gumps or The Bungle Family. The comparison with The Gumps is apt because the writer of the strip, Sol Hess, got his start ghost-writing for Sidney Smith. But whatever magic he brought to The Gumps was lost when he decided that his own strip would have less abrasive characters and more down-to-earth stories. Dull as dishwater, in other words.

Perhaps I'd give the strip more of a chance if the art by Wally Carlson wasn't like fingernails on a blackboard to me. And I don't know what it is about it that I hate! It's perfectly capable work, if a little sterile and perfunctory, but for some reason I can't stand it. (Just to get it off my chest, Jimmy Hatlo's art has the same effect on me.)

Anyway, Mr. Hearst and I will simply have to agree to disagree. The Nebbs was undeniably a successful strip, and not just in Hearst papers. In the 1920s and 30s it has been claimed that it ran in over 500 papers, and even back then that was an impressive number. So somebody must have liked the darn thing.

Anyway, this post is not just a pointless whining session. It's about the main topper of The Nebbs, Simp O'Dill. This strip about a simpleton began on February 24 1929* as a small one-tier topper, as was the style with Bell Syndicate at the time. He had no real personality, he just acted out 'dumb guy' gags straight out of joke books. He seems to have appeared out of nowhere, or at least I am not aware of him ever being a character in the main strip.

On September 16 1934, Simp O'Dill was enlarged to a two-tier format, becoming a full-fledged half-page strip. The strip did not really change in any way except that it took twice as many panels to tell the same bad jokebook gags. The idea, of course, was to make The Nebbs a better-selling Sunday by making it easy to substitute a half-page ad for the topper. Newspapers seemed to really appreciate this format, and I imagine it gave Sunday sales of The Nebbs a nice little bump.

In 1936 Hess decided to add activity panels to the topper mix, but generally they just shaved a single panel off of Simp O'Dill to squeeze them in. Simp, just like The Dude, abides.

In 1941 Sol Hess died, but his duties were continued by Betsy and Stanley Baer, and both The Nebbs and Simp O'Dill soldiered on without a stumble. Though newspaper readers began to lose interest in The Nebbs in the 1940s, the Sunday half-and-half setup allowed Simp O'Dill to survive when many other toppers got the axe. But to all good, bad and indifferent things there must be an end, and so it was with Simp O'Dill. It last ran on January 4 1948**, and The Nebbs Sunday was thereafter no longer available in a full page format.

* Source: Tucson Citizen

** Source: St. Cloud Times

Labels: Topper Features

Monday, January 08, 2024

Obscurity of the Day: Pauline McPeril

In the 1960s there was a fad for silent movies. Unfortunately the fad had nothing to do with an appreciation of them, but rather was all about making fun of them. I distinctly remember as a kid an afternoon show on one of the non-network channels that ran silent films, mostly comedies. They would never run entire films, but rather just show snippets, lots of chase scenes and high drama moments, played at breakneck speed. There was always a voiceover that said snarky things about what was going on.

This ridicule of silent movies also found its way into sitcoms. On Gilligan's Island, The Beverly Hillbillies, and the like, they'd cut to rinky dink piano music and a chase scene played at double speed, all as an *ahem* homage to those great silent comedies.

During this odd fad, a sort of sub-fad was for the silents that featured women in danger. The classic situation being where the girl gets kidnapped by an enemy of her hero boyfriend and the fiend straps her onto a log-cutting saw or ties her onto railroad tracks. There really were films like this -- the most famous of which was The Perils of Pauline -- and they were being made fun of even back then in the comics; Hairbreadth Harry and Desperate Desmond being two examples.

I venture to guess that more screaming Mimis got tied to railroad tracks in the 1960s on TV sitcoms, variety shows and Saturday morning cartoons than ever occurred in the silents. But no matter, that finally gets us to Pauline McPeril, today's obscurity. Hoping to cash in on this sub-fad was a team of two A-listers, writer Mell Lazarus (of Miss Peach) and artist Jack Rickard (one of the leading lights in the usual gang of idiots at Mad magazine). Lazarus either chose or was asked to use a pseudonym on the strip; he went by "Fulton."

Pauline McPeril was a contemporary-set mod action-comedy that offers the breakneck pacing, overblown situations and constant danger made famous by the old silent serials. It debuted on April 11 1966* as a Sunday and daily feature through the auspices of Publishers Syndicate.

Rickard was a big catch, coming as he did with a built-in audience of Mad-crazed teens who would eagerly follow him anywhere. And Lazarus, though we might disdain the derivative subject matter, offered up a superbly fast-paced screwball story that plays the genre for all its worth. Yes, it's overblown, silly and half-baked, but that's the whole idea!

Why, then, did the strip fail so completely that it didn't even manage to make it to its first year anniversary (the daily cancelled in mid-story on February 11 1967** and Sunday ended, also in mid-story on March 5***)? My theory is that newspaper editors looked at this strip and they recognized that this sort of thing was a mere fad, and that they'd be looking for a new feature in a few years once the fad wore out its welcome. Forget the built-in audience craving this, the editors probably felt, they'll tire of it in a year or two and then I'm out there beating the bushes for its replacement. Evidently it didn't occur to them that a team of seasoned pros like Rickard and Lazarus would likely be smart enough to adapt the strip to changing times. On the other hand, Lazarus said in later years that he didn't have a clue how to write continuity, and that's why the strip didn't work out. I have to disagree with that; I think he did a fine job within the restrictions of the genre.

In the final reckoning we really can't blame newspaper editors for being too lazy to take a chance on Pauline McPeril -- that's just their normal behavior. You don't blame a lion for killing a poor defenseless antelope -- they're just doing what is in their nature. The blame lays with the creators and the syndicate who didn't figure out that this particular strip was not going to hit the jackpot. The dream team was squandered on this derivative stuff when they could have come up with an original concept that had legs. Too bad!

* Source: Tampa Tribune

** Source: Jeffrey Lindenblatt based on South Bend Tribune and others.

*** Source: Newark Evening News.

Labels: Obscurities

Beginning in the late 50s silent comedy became trendy with a famous LIFE article by James Agee and a successful series of compilation films by Robert Youngson ("The Golden Age of Comedy", "When Comedy Was King", "Days of Thrills and Laughter", etc.). There was a half-hour syndicated show that added hokey music and somewhat earnest narration to Chaplin two-reelers, and another syndicated item called "The Funny Manns" where a modern host would narrate clips as tales of his forebears. Jay Ward's "Fractured Flickers" would carve up comedies and dramas every which way, adding new dialogue and a laugh track ("Hunchback of Notre Dame" became "Dinky Duncan, Boy Cheerleader"). There were also more reverent showcases, with TV shows like "Silents Please" and a growing number of museum and college revivals. Chaplin and Harold Lloyd both oversaw repackagings of the films they owned, and Buster Keaton was recognized as a superstar at film festivals. By the 60s the fad had faded a little, but people were more generally aware of silent films and the cliches.

I daresay the real impetus for "Pauline McPeril" was the television show "Batman", which combined 30s-40s movie serials and dowdy 1950s-early 60s DC comic stories (still heavily reprinted in the 80-page reprints). But in contrast to Stan Lee's parody soap strip "Vera Valiant", where the main joke was always the mock seriousness, "Pauline" prioritized outright comedy. That alone should have extended its shelf life beyond what it got.

Possibly related: There was an unsold TV pilot packaged as a theatrical film in 1967, "The Perils of Pauline". Though the premise is slightly different -- Perky blond Pauline and George grow up together in an orphanage, and out in the world Pauline keeps encountering perils that keep her from marrying George -- it's set in the present and goes for the same gag-driven humor. Might there have been a few lawyer letters between the syndicate and Universal over resemblances?

That Agee article in LIFE was in September 1949. His choices for the three most important silent comedians were Chaplin, Keaton and Harry Langdon. I'm pretty sure few would have agreed with the last name, (What about Harold Lloyd?) and Harry got a posthumous career boost. But even by that time, though silent film production was dead twenty years, the older films were still part of the firmament, as there were millions of hobby film collectors and film libraries where 16mm prints of the still-funny films circulated. Most were already public domain, so they became free fodder for early television.

Though Robert Youngson made a big impression with his compilations, the silent comedians were still a staple of TV. "Howdy Doody" showed lots of them (with the Titles stripped out) and the very same prints were recycled as "The Funny Manns" series. (introduced and narrated by Cliff Norton.)

Of course Funny Manns, and likewise "Laff-a-Bits", "The Chuckleheads", "Mad Movies" etc. are a pretty poor way to be introduced to silent comedy, I guess the worst was "Fractured Flickers", which just trashed the films, including running footage backwards, including pieces of other films, and even de-tracked talkie clips.

My late brother Cole, familiar to long time readers of this blog, was a truly devoted man about preserving, showing and studying this very subject. His series of programmes at the Museum of modern Art in New York brought to light many forgotten great and not so great titles, culled from various sources, and I believe, influenced and inspired many who now share this passion. Or as Cole often said, "Those who are similarly afflicted."

Sunday, January 07, 2024

Wish You Were Here, from Albert Carmichael

Here's another entry from Carmichael's 1910 "If" series #262, published by Samson Brothers. I wasn't sure which way to display this card, since the text and the image are at odds with each other. Isn't there an old maxim "In a Tie Game, The Toon Wins"?

Labels: Wish You Were Here