Saturday, November 25, 2023

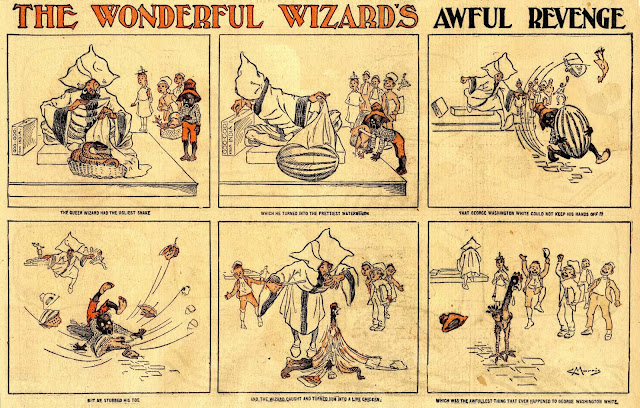

One-Shot Wonders: The Wonderful Wizard's Terrible Revenge by Morris, 1904

This one-shot strip that ran in the World Color Printing Sunday comics section of December 4 1904 generates so many questions. Why does the wizard turn a snake into a watermelon? Why does he finger a mysterious case labelled "Goo-Goo From India"? Why does the wizard turn George Washington White into a chicken particularly? I'm so confused...

This one-shot is signed Morris. He was not an artist in World Color's regular stable; in fact this seems to be the only strip he contributed to the syndicate. Nice art, but that gag needed some polishing.

Labels: One-Shot Wonders

What's the snake about? It's introduced to no effect; and why was transforming into watermelon done? More questions can be considered as well, but it's more than it's worth.

Friday, November 24, 2023

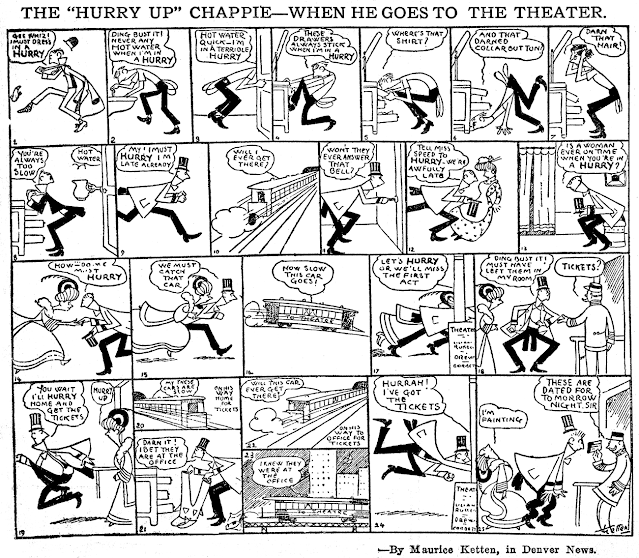

Obscurity of the Day: The Hurry Up New Yorker

I rarely get to feature Maurice Ketten* on the blog because he worked on his daily panel, often titled Can You Beat It?, for the New York World pretty much for his whole newspaper career. But that's a shame because though his later style lost most of its allure, in his early days at the World he was a pretty incredible stylist. His work was so distinctive that the World billed him as "the Angle and Curve Cartoonist." His style at that time was so highly stylized I tend to think of it as Art Deco, or perhaps Cubist, and that's well before either of those were even things.

As Ketten settled in at the World in 1906 his style quickly became more conventional, and to imitate T.E. Powers over at the New York Journal. However, in his only series that predates Can You Beat It?, The Hurry Up New Yorker, the vestiges of his "angle and curve" days are still in evidence. This series makes fun of Big Apple denizens, who always seem to be scrambling to make time. Of course in Ketten's series this always backfires to comic effect.

The series ran from October 19 to November 17 1906**, predating Ketten's decades-long series Can You Beat It? by a few months. As you can see from the samples above, which ran in other papers, the original title was changed to suit the local paper, sometimes made generic like these, other times by substituting the name of the newspaper's city.

* Ketten's real name was Prosper Fiorini; he changed it when he came to the U.S.

** Source: New York Evening World.

Labels: Obscurities

Wednesday, November 22, 2023

Ink-Slinger Profiles by Alex Jay: Frank Robbins

... Robbins was a Grade-A prodigy of the drawing board in his native Boston at the age of four, won several art scholarships at 9, painted giant murals for his high school at 13 ...

“I began life back of the North Station in Boston … precisely on the wrong side of the tracks! At fifteen [around 1933], my family came to New York, lived on the East Side and I began my professional career.”After kicking around as errand boy in ad agencies, Frank, at the age of sixteen, came under the eagle eye of Edward Trumbull, well-known muralist. Trumbull was then color director of the Radio City project, and through him Frank met the architects and contractors for the buildings being erected. He immediately received commissions to do pencil portraits of all the architects and other personalities connected with the construction project. Upon completion of this lengthy and challenging job, Frank met the Rockefellers and received a grant from them to study and paint. A year later, in a studio given to him in the Graybar building, Frank was busy working on a series of mural sketches for the then proposed Children’s Broadcasting Studio in the RCA building. The sketches were approved when then NBC studios opened for a full schedule of broadcasting. Since the murals were to be painted directly on the walls this gave Frank the choice of working for three months in the wee hours between midnight and early dawn or forgetting the whole deal. Due to his health at the time Frank had to regretfully drop the project.

At about the same time he’d been doing Scorchy Smith, Robbins also drew Lightnin’ and the Lone Rider, a thinly syndicated cowboy strip. This poor man’s Lone Ranger had originally been drawn by Jack Kirby.

Frank is now married, and his lovely wife, Berta, helps him on research and the more pleasant matters of life. “Frankly,” Frank confided to me, “Any similarity between my comic strip heroines and my wife are pure coincidence!”

“I taught English there,” she said. “I met Frank while I was directing a play reading of Amadeus.”“His wife had died two years before I met him … We were together for about five years. We had a wonderful marriage. It was a big loss when he died, let me tell you.”

“We had a sound system that was second to none. ... He created a single cone speaker that was astonishing. It was very pure sound, very clear. wonderful, wonderful. He knew a lot about sound. He had boxes and boxes of research about sound.”

Labels: Ink-Slinger Profiles

Monday, November 20, 2023

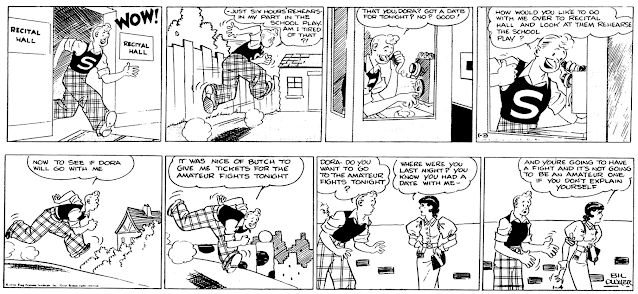

Firsts and Lasts: Dumb Dora's Not So Dumb ... But Cancelled Anyway

Dumb Dora was on its third artist, or more like a hundred and third if you count ghosts and assistants, when her strip was retired in January 1936. Bil Dwyer was the final credited artist on the strip, taking over in late 1932 from Paul Fung, who in turn had taken over from Chic Young.

Dwyer reportedly brought on a small army of helpers to get the Sunday and daily strip out on time, including Milton Caniff, who R.C. Harvey reports did much of the pencilling for the initial eighteen months of Dwyer's tenure, plus inking some of the girl characters. By the time Dumb Dora ended Caniff was long gone, but we can still easily see vestiges of his style on the dailies above, the last two of the series.

Dumb Dora had begun as a me-too flapper strip in 1924, but had the additional hook that Dora acts dumb but usually turns out to have a bean firing on all cylinders by the end of each gag. The concept is fine, but awfully repetitive. By the time Dwyer took over the conceit was well and truly played out, and flappers were long gone, so the strip had turned into a more generic "teen boys chasing the pretty girl" feature, which left it drowning in a sea of its betters -- Tillie the Toiler, Harold Teen, Winnie Winkle, Etta Kett, etc.

Mark Johnson supplied a scan of the last two rather rare dailies seen above, which offer no farewell or conclusion to the strip. So I went looking online to see if the Sunday, which ended the next day (January 5 1936), offered us some closure. Nope!

Labels: Firsts and Lasts

My guess is that the feature lasted as long as it did because Dora had been such famous character that her very name became part of the popular American idiom, everybody said it, there were "Dumb Dora Clubs" organised by college girls; a "Dumb Dora" was a shorthand description of a He said-she said joke or cartoon gag.

Thing is, though still well known, it became stale. It was corny. The name was associated with the 1920s.

It was like calling your strip "Oh You Kid" or "Sheik n' Sheba". And all those change of artists didn't help. There's nothing interesting story-wise, either.

Yung was the only one who really understood the character and material to suit her, perhaps Fung did as well to some extent, but by the time it was dumped on Dwyer's drawing board, the feature had lost its soul.

Gene Rayburn: Dumb Dora is SO dumb . . .

Audience: HOW-DUMB-IS-SHE?

Rayburn: She thinks "Night School" is where you learn how to be a ______.

I never knew it was a comic strip reference. I wonder how many people did.

https://comicskingdom.com/trending/blog/2015/09/10/ask-the-archvist-dumb-dora

Sunday, November 19, 2023

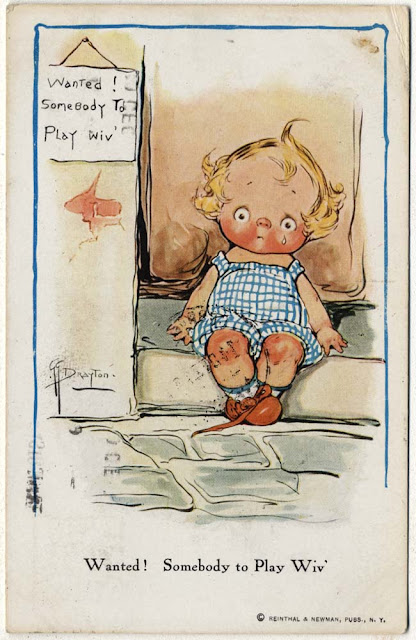

Wish You Were Here, from Grace Drayton

Here's a Grace Drayton postcard issued by Reinthal & Newman as #250. Drayton's cards in this series were generally quite humourous, but this one just tries to elicit compassion for the typical Drayton waif.

This card was postally used in 1914, sent from Great Britain to Portugal. Eventually it ended up in a Florida antique store, where I bought it and then brought it here to Nova Scotia, Canada. That is one well travelled postcard!

Labels: Wish You Were Here