Saturday, February 20, 2016

Herriman Saturday

Wednesday, November 4 1908 -- We have a winner! William Howard Taft becomes the 27th President of the United States. It's amazing that they could count and communicate the votes quickly enough to declare a national winner overnight in 1908!

Is it just me, or would Herriman's Uncle Sam be great to play the role of a creepy old school groundskeeper at the high school where the cheerleaders keep disappearing in a slasher movie? He's even got his own pet buzzard!

Labels: Herriman's LA Examiner Cartoons

Friday, February 19, 2016

Walt McDougall's This is the Life Chapter 9 Part 2

This is the Life!

by

Walt McDougall

Chapter Nine (Part 2) - THE WORLD, THE FLESH AND THE DEVIL

Of all the reputations that have burgeoned from the World's

upgrowth, that of Nellie Bly (Elizabeth Cochrane) was the most far-reaching and

the most brilliant as far as mere acclaim went. Her appearance was at the

precise moment when sensations were coming so fast and so plentiful as to begin

to pall and a fillip was needed. This was supplied by femininity. A voyage through

the Minetta sewer or a fake bomb attack on a British man-of-war no longer

stirred the jaded senses, but done by a girl with a name like Nellie Bly, which

was given her by Erasmus Wilson of the Pittsburgh Gazette, a name that rang

with a musical note, any live story was bound to register.

She was of medium height, shapely, with gray-blue eyes in a

pointed, eager face, her voice with that indescribable rising inflection

peculiar to West Pennsylvanians, and dark

brown, slightly wavy hair. In many ways she closely resembled Annie Oakley,

that shooting star of the Wild West show. She was but a month or so over twenty

when she came to the World in 1887, but she had been three or four years

engaged in newspaper work of various sorts. She had, however, no real training,

but for the work in which she was engaged she needed none. Her sole assets were

courage, persistence and a modest unassuming self-confidence.

|

| Nellie Bly |

She was sprightly, yet not frivolous; like Nye, everybody knew her but she had very few familiars. Not a deep mind but a warm and sensitive heart. How the idea of her trip around the world germinated, I have forgotten. I can only remember her state of wild excitement as she rushed in and announced it. We both imagined, at the time, that I would accompany her, but we were promptly undeceived. No such luck!

Never has a newspaper received such advertising. Indeed, we fancied in the office that her progress around the globe was creating as much excitement and interest in Thibet or Kamchatka as on Park Row, but Nellie found many spots where the World was as yet unheard of. She started Nov. 14, 1889, and returned, via Pittsburgh, where some of us went to meet her, on Jan. 25, 1890. In Amiens, France, she contrived to interview Jules Verne, doing the best bit of literary work of her career under circumstances that could not fail to be inspiring. We made countless trips together, and I came to know her well. Nothing was too strenuous nor too perilous for her if it promised results; in sooth, she was more than once held back from a too dangerous venture, for she suffered the penalty paid by all sensation-writers of being compelled to hazard more and more theatric feats. Once we organized a round-up of all the celebrated alleged haunted houses in Connecticut, one of which I now own and occupy in summer, and we spent more than a dozen chill comfortless nights, before flashlights were invented, sitting up waiting for hitherto dependable and unfailing spooks, who, on these occasions, failed to make good. This trip was a dreadful fizzle.

One of her first big hits was managing, under pretense of insanity, to be sent to the insane asylum on Blackwell's Island, where she obtained material for a story exposing its methods, but there was considerable difficulty experienced in effecting her release. I went with another man to bring her back and, being left alone in the inner court of the asylum for a few minutes, almost had my clothes torn off by a raging crowd of female maniacs, idiots and plain bugs. The way that mob rushed me, one would have thought I was the first train out after a subway hold-up.

At the height of Nelly Bly's fame, the supply of what we now call "hokum" began to fail. She had shone for about ten years, the usual limit of a celebrity in New York, as a rule, when the New York Ledger, I think it was, made her a splendid offer for a serial story, which she accepted with intense complacency but with no plot, characters or ability to write a dialogue. She soon came to me in genuine distress, confessing that she could not start the story and demanding help. There came to my mind the distant days when Ned Buntline and Cody used to dig up enough thrillers in two hours to last the author a whole week, and I said with seeming seriousness:

"That's perfectly easy. You've merely to start off with a big thrill. Have your hero fall into a deep pit filled with big rattlesnakes, and go on to describe his terrors."

"But how'll I keep the snakes from biting him?"

asked Nellie, deeply intrigued.

"He had a bottle in his hip pocket. It breaks, and the rattlers all keep their distance—but you don't mention this until you've written three or four thousand words, at least."

"It sounds great!" Nellie purred. "But how am I going to get him out?"

"It doesn't matter. Any old way. Of course the heroine—and to the reader, that means you—must get him out, but the real punch is in his terrible situation. You can get him out with an ordinary barn ladder, a well-rope or even a hop pole, nobody will notice —"’

"Yes, well, after that?" she demanded.

"Keep on getting him, or her, into more just such holes, one in each chapter, until they get married or take out accident insurance, when, of course, the story must stop, but don't bother me any more! Get the first chapter started."

She went off, and that was the last I ever heard about it, but she started the story off as outlined, and it ran I know not how many weeks.

Nellie was deeply attached to a friend of mine, and when he suddenly married another she abandoned New York. I never knew, nor does anybody, I suspect, what her intentions were, but on the way to Chicago she met an iron manufacturer named R. L. Seaman, aged seventy-two, and to everybody's amazement promptly married him. She was not yet thirty, in 1895, and when, nine years later, he died, he left her very wealthy. How her estate was deftly and smoothly taken from her by those to whom she confided its management is only another tale of a woman's trust in man. Poor Nellie had not known any of this sort, having only associated with newspapermen.

There were other famous and near-famous women on the World at various times—Harriet Hubbard Ayer, Marion Harland, Meg Merrillies, Elizabeth Jordan, Ella Starr, Edith Sessions Tupper, Kate Masterson, Dorothy Dix—but none with the fire and flame of Nellie Bly.

She died Jan. 27, 1922.

Another now-almost-forgotten meteor blazed into glory on the World and shone for years in the theatrical firmament, Henry Guy Carleton, by all odds the cleverest, most gifted all-around mortal whom I have ever encountered. A graduate of West Point, an electrical inventor, a wonderful descriptive writer and reporter, a successful playwright, an ardent fisherman and a superb cook, he was, withal, witty, sympathetic and affable. He had an aversion to pretense and affectation that sometimes tinged his speech and writings with bitter satire, and that impatience with stupidity which characterizes all men of brain, but the butt of his keenest wit was oftenest himself.

Coming to us from the Times, he made his first hit with a four or five-column story of the French Ball, an annual function of the depraved and abandoned, which each year shocked every police official, and others, into strict attendance for several hours, through which story the strains of "The Beautiful Blue Danube" were woven in words that brought the music perfectly to the ear of the reader, a remarkable literary feat. He wrote many plays, nearly all of them very successful and remunerative, yet he could never manage to keep out of debt. After his first wife had divorced him, he married Olive May, and when that venture miscarried, Effie Shannon, both well known, charming and altogether lovely actresses, but Henry was not built for matrimony and when Effie also had recourse to the court, he eschewed the practice.

He stuttered painfully, but he made this defect, which seriously hinders the career of most men thus afflicted, a source of amusement and jesting. One of his notes to me read: “Come over to my office for a couple of hours; I want to talk with you for ten minutes." This indicates the true stature of his mentality. He told me once, when relating incidents of his brief army career, that when he was a lieutenant with the troops in the West, his company was engaged in an attack upon a body of Indians entrenched at the top of a hill. As they charged up the slope, Carleton followed in the rear of his company, waving his sword and loudly shouting: "Ha!—Ha!—Ha!—Ha!"

"I was cited for conspicuous bravery in the face of the enemy for this," he added, "when all the time I was merely trying to say 'Halt!'"

He had an exhaustless fund of good stories and delighted in monopolizing the conversation, which his unique stutter materially assisted in doing. At Bronson Howard's house, on an evening when he was particularly entertaining, I heard a woman ask him: "Mr. Carleton, when did the impediment in your speech first begin to affect you?"

"W-w-w-h-h-en I b-b-b-e-egan t-to t-t-t-a-alk!" he sputtered with a highly delighted grin.

We wrote a play together entitled "The Summer Boarder," and Charles Frohman agreed to produce it. All I know about playwrighting I learned during the months spent on this piece, which satirized the efforts of snouty prudes and self-selected censors of the theater and literature and which, in truth, would be timely today. Frohman changed his mind on the ground that a character in the play, who is mistaken for an insane man, might distress tender-hearted auditors who had friends or relations in the asylum! On such trifles does the fortune of a play depend.

Then Billy Brady agreed to produce it, for he was a speculative manager who was willing to leave a little thing like that to the judgment of the audience, but Henry quarreled with him over a play he was doing for Jim Corbett, and "The Summer Boarder" never, never saw the footlights. I still have the third act, Brady has the second, and Carleton mislaid the third! It is recalled by me now merely because it was supposed to be a very risque and daring departure in that the plot rests on the possession by the hero of the heroine's garter! Of course, we handled that delicate situation most squeamishly, never actually showing the garter on the stage, for we knew too well the danger of flying in the face of public decency and morality, but the salacious suggestion of garter was always there, lurking in the background. Perhaps it was this dangerous sex element that really deterred Brady from putting the play on, and not his quarrel with Carleton. A manager had to watch his step in those days, when Olga Nethersole's non-stop kiss, and an actor actually carrying a woman upstairs, created an uproar among the clean-minded that was heard out in Morristown, N.J.

When Carleton came to live in Atlantic City, a stroke of paralysis had deprived him of speech entirely, but this indomitable spirit was not to be subdued. He had constructed a large alphabet framed in glass, upon which he would spell out words with a cane and thus converse with his friends. Frequently he would become irascible, swear fluently, and then smash the glass, thereby keeping a glazier in fairly constant demand. Yet even under the handicap of paralysis, that active brain found occupation, and he soon invented a superlative sauce which became very popular and amply provided for his needs.

Many misty, half-formed figures lurk among the shadows of those years, appearing fitfully as distinct shapes and then fading into the gloom. Ignatius Donnelly, the gifted and eccentric author of "Atlantis" and "Ragnarok," who lived in Minnesota but who appeared annually on Newspaper Row, probably for his settlements with Harper's, was always seemingly pinched for money but always jovial and disputatious. I was, and am still, one of his devoted followers, a catastrophist and an iconoclast like himself, and I am delighted whenever I see one of his prophecies come true. When he began to write about Atlantis, the whole world was united in regarding the tale of the Lost Continent as pure fable, but it is now getting ready to do some deep-sea diving in order to settle just where the mythical city was located.

Lafcadio Hearn is another of these dim shapes. Slouchy, negligent, unshaven, generally petulant, always broke and so shortsighted as to be unable to recognize anybody a yard distant, he courted Col. Cockerill assiduously, making my room his base of operations. He was usually rather reticent but on occasion would talk brilliantly, but somehow I always regarded him as an infliction, I suppose largely because he rarely had discretion enough to withdraw when a lady called upon me. I will frankly admit, in face of the fact that I was drawn into the Gould-Hearn-Bisland dispute through frankness, that in spite of having numerous opportunities, I never really became well enough acquainted with him to discern the hidden charms that many saw plainly. Frank Munsey, running a magazine with a packing-box outfit, used to come in after small and cheap pictures for headings, a slight, thin, hungry-looking and nervous figure, with a hayseed taste in attire that he was never able to subdue sufficiently to make him look urban —and has not yet. He was averse to paying regular prices for his pictures, and he was extremely slow pay, as well. But a more self-confident man I have never encountered. S. S. McClure, P. F. Collier, Fenno, Richard K. Fox, John Brisben Walker and other publishers had their moments of gnawing doubt, but Munsey never showed the least uncertainty even when hanging over the brink. He has never admitted that there was one moment when he was not convinced that he was to be the greatest publisher on earth.

There was Tupper, the Long Island poet, Dan Rice, the much married clown, Si Pickering, the jeweler, a natural comedian, Bryan Hughes, the incorrigible joker, Louis Mann, a young actor with the largest faith in himself of any living man, and Commodore Roome, who invented the burglar alarm and was rapidly becoming a millionaire, Henry Clews, John Mackey, Wicked Fred Gibbs, Baron Blanc, Ed. Weston, Schuyler Hamilton, Nathan Strauss, Fremont Cole, Henry George, Gompers and a regiment of others; a mixed and various company.

Don Seitz states in his "Life and Letters of Joseph Pulitzer" that on the occasion of the World's circulation reaching one hundred thousand, J. P. presented every member of the staff with a high hat. I do not remember one of the staff ever wearing such a headpiece except Jim Townsend, the society editor, who was weaned in a crush hat. I think this event was before Don's day, and it may also have happened early in the morning, before I got to work, but I think I would have heard about it. I well remember that day, and the actual truth is—and I regret, of course, to record it—that all of us who could be spared from the office went over to the Astor House and few returned. A bronze figurine about a foot high had been purchased by subscription, and in the midst of the festivities this was presented to Col. Cockerill, although my impression is that it was intended for the Chief, but I confess to a decided haziness as to details. Also, my ears were never stunned by salvos of cannon on City Hall Square or elsewhere.

We all used to get many presents, but I suspect that J. P.

was not so freely favored. One day he came into my room and remarked, as if

quite casually: "I notice that once in a while you put the name Grand Sec on

a bottle in a cartoon. What do you get out of that?"

"Oh, that's a champagne sold by friends of mine, the Somborns," I ingenuously admitted. "They send me a case of it, now and then."

"Well, I never get any champagne!" he grumbled, but I noted a twinkle in his luminous eye.

"Why, I'll tell them to send you a case instead of to me, I never drink the measly stuff," I said. "I drink beer!"

He laughed and walked out. I promptly notified Eddie Somborn (who, by the way, was the original promoter and biggest stockholder in the first "Rubberneck wagons," to attend to the matter, and the next day he delivered a case of his finest vintage with a flowery note. J. P. came galloping down to my room as tickled as a boy, and I think he became a good customer of the Somborns.

Increases in salary are white stones marking the long road in every worker's life, and the longest life is not marked by them so plentifully that any are overlooked. My first increase came through the agency of William C. Reick, a Philadelphia boy working in Newark, whom my brother Harry secured for the Herald and who became its editor. Billy was a good-looking, conceited chap, rather pompous, but affable and courteous to his equals, and he always took off his hat to Bennett even when talking to him over the long-distance telephone. During his years on the Herald he amassed something like $800,000, according to Mr. Bennett, which demonstrated that he knew the newspaper game. When Bennett dropped him, he bought the Evening Sun, but it deteriorated under his management.

I met him on Park Row one day in '89, I think, and as we walked along, he asked me what J. P. was paying me. I told him I was receiving fifty dollars a week.

"Bennett wants you, and he will give you seventy-five," said Reick. “Wants you to do a daily cartoon and no other work."

"I'll let you know tomorrow, Billy," I gasped. "This is so sudden!"

I went to J. P. and, with ill-concealed elation, informed him that Bennett was after me, although I had no intention of accepting the offer, for I despised both Bennett and the Herald. J. P. regarded me with a pained and puzzled expression for a minute, and then with sudden decisiveness snapped out:

"I'll make it a hundred and ten dollars. You go away and be a good boy and don't bother about Bennett!"

Labels: McDougall's This Is The Life

Thursday, February 18, 2016

Ink-Slinger Profiles by Alex Jay: Richard Taylor

Richard Lippincott Denison Taylor was born in Fort William, Ontario, Canada, on September 18, 1902, according to Who’s Who in American Art, Volume 9 (1953). A family tree at Ancestry.com said Taylor was named after his father. Taylor’s early years and career were told in Current Biography Yearbook, Volume 2 (1941).

…[Taylor] was born in Fort William, Ontario, Canada, of English descent on his father’s side; Scottish-Dutch on his mother’s. As a child he was always drawing, and at 12 he began his formal art education “under a conservative landscape and figure painter, an associate member of the Royal Canadian Academy.” Later Taylor studied at the Ontario College of Art and the Los Angeles School of Art and Design. “No university education. No degrees. No honors.” Throughout school, he confesses, he was very dull in everything but history and literary composition, in which he got high marks; “had no mind whatever for mathematics or problems of any sort.”…Lambiek Comiclopedia said Taylor drew the Mystery Men comic strip for the Toronto newspaper, Evening Telegram, in 1924.

Taylor first began drawing cartoons in 1927 for the Goblin Magazine, a Toronto University publication which by that time had become a professional journal. He drew for it until it folded and then “lived precariously doing all sorts of commercial art in Toronto.” He painted in his spare time, successfully enough to exhibit with the Ontario Society of Artists and once with the Royal Canadian Academy, though he was never elected to membership in either body.

A record of Taylor’s first entry into the United States has not been found at Ancestry.com. The 1910 U.S. Federal Census recorded Taylor and his parents in Los Angeles, California at 4075 Normandie Avenue. Taylor’s father was a real estate agent. Sometime after the census, Taylor returned to Canada.

Taylor’s next entry into the U.S. was at Port Huron, Michigan, July 24, 1917, according to the border crossing card at Ancestry.com. Taylor was accompanied by his mother. In Canada, his address was 96 Pinewood, Toronto, Ontario. His destination was to “Intr. Janet Young, 113 Curtis, Alhambra, California”. Taylor later returned to Canada.

On October 7, 1919, Taylor passed through Buffalo, New York. He had left Toronto on his way to his father in New York City at 1133 Broadway.

In the 1920 census, Taylor and his parents resided in Manhattan, New York City, at 608–610 West 139 Street. Taylor’s father was a manufacturer in the poultry food industry. Taylor was an art student. After the January census enumeration, Taylor returned to Canada. Passing through Niagara Falls, New York, on September 30, 1920, Taylor was on his way from Hamilton, Ontario, to Brooklyn, New York, at Bridgewater Street and Meeker Avenue. His contact in Hamilton was “Aunt, Mrs. Povis Herkimer”. Once again, Taylor returned to Canada.

The family tree said Taylor’s father passed away April 5, 1929.

American Artist, February, 1946, published “A Visit to ‘Worm’s End’” by Ernest W. Watson who profiled Taylor and explained how he became a cartoonist for the New Yorker magazine.

Now we come to 1935 and a change in the Taylor fortunes. A friend had written a book entitled, Worm’s End, a sort of adult’s Alice in Wonderland. Taylor read the manuscript and, convinced of its merit, proceeded to make forty drawings for it. These he did somewhat in the manner of Tenniel who had illustrated Lewis Carrol”s famous fantasy.A travel document with the 1935 date has not been found, but there is a border crossing card that recorded Taylor’s arrival in Buffalo on June 3, 1936. His address in Toronto was 632 Church. The card said he had been in New York City from 1921 to 1922, and his destination was “The New Yorker Magazine”.

The pictures completed, Taylor wrapped them up with the manuscript, headed for New York and the publishing house of Simon and Schulster. The manuscript, which Taylor still thinks is good, did not impress the publishers; but his drawings did. Clifton Fadiman, who was then with that firm, was particularly encouraging; he told Taylor he ought to be drawing for the New Yorker and he even offered to show the Worm’s End drawings to its editors.

Awaiting word from the New Yorker, Taylor spent a few cheerless days in one of Manhattan’s cheap hotels and then, hearing nothing, returned disheartened to Toronto. In a few days, however, hope was rekindled by the receipt of a letter from the magazine inviting him to submit cartoons. He lost no time doing so; during the next six months he devoted himself almost exclusively to the drawing of New Yorker cartoons which, distressingly enough, didn’t get into the New Yorker. He was about to give up in despair when a check for $15 revived the spark of hope that he has managed to keep alive all those months. He had sold a drawing, if only a small spot, to the New Yorker!

That was the beginning. Soon more checks, bigger checks began arriving, and Taylor came to the conclusion that he ought to be nearer the source from which all blessings flow. Accordingly, in 1936 he bade farewell to Canada and set himself up on Port Chester, New York, forty miles from Manhattan. There he married Maxine MacTavish, daughter of Dr. Newton MacTavish onetime critic and former editor of the Canadian Magazine. This was about the smartest thing Taylor ever did, “Max” casts a critical eye upon all his drawings and tells him what, if anything, is wrong with them. He considers her judgment infallible.

The 1940 census said self-employed cartoonist Taylor and his wife lived in Bethel, Connecticut at 38 Putnam Park Road. In 1935 Taylor was a Toronto resident. His highest level of education was the eighth grade.

Life magazine, April 22, 1940, reported on the cartoon show at Museum of Art at the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence. Taylor was one of 39 cartoonists in the show. Art Digest, December 15, 1940, mentioned Taylor’s solo show.

Taylor helped paint and decorate his neighbor’s house as covered in the September 13, 1943 issue of Life. A few weeks later, Taylor and a self-portrait were published in Life, October 25, 1943. Life, November 27, 1944, showed selected cartoons from the books of Virgil Partch, Rube Goldberg, William Steig, Peter Arno, and Taylor.Humor of Richard TaylorReaders of The New Yorker who take special delight in the bug-eyed characters drawn by Richard Taylor will get many a chuckle out of the large show of his unpublished drawings on view at the Walker Galleries in New York through Dec. 28. The exhibition provides a happy hour backstage with a deft draftsman whose eye for humanity’s foibles is sure and keen. His pen, dipped in just enough acid, pierces the very core of fatuousness, pomposity and other frailties of our characters.

Random House, 1944

American Newspaper Comics (2012) said Taylor was one of several cartoonists and illustrators who worked on the Calvert Reserve Whisky advertising panel, Metropolitan Moments, during the 1940s. Samples of Taylor’s Mennen and Ry-Krisp advertisements can be viewed here.

Taylor’s Introduction to Cartooning was published by Watson-Guptill Publications in 1947 and was advertised in Life, December 1, 1947.The Wilton Bulletin (Connecticut), May 27, 1970, said Taylor also studied at the Florence Kane School of Painting [sic; Art] and with Vaclav Vytlacil.

The family tree said Taylor’s mother passed away February 8, 1951.

According to Who’s Who in American Art, Taylor resided in Blandford, Massachusetts on Otis Road. Taylor also contributed cartoons to Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s, Esquire, American, Town & Country, Mademoiselle, Life, McCall’s, and Playboy.

Simon & Schuster, 1961

Taylor passed away May 25, 1970, in West Redding, Connecticut. He was buried at Umpawaug Cemetery.

Further Reading and Viewing

Billy Ireland Cartoon & Museum Blog

Canadian Magazines

Heritage Auctions

—Alex Jay

Labels: Ink-Slinger Profiles

Wednesday, February 17, 2016

Ink-Slinger Profiles by Alex Jay: Herbert Roese

In the 1905 New York state census, Roese was the second of three sons. The family lived in Manhattan, New York City at 410 East 81 Street.

The 1910 census recorded the family of five in Bronx at 450 East 171 Street. The family remained in the Bronx, at1320 Webster Avenue, according to the 1915 state census.

Information about Roese’s education and art training has not been found.

On Roese’s New York World War I service card, he resided at 1256 Clay Avenue in the Bronx. He enlisted on September 20, 1917. As an Army private he served overseas from October 18, 1917 to February 12, 1919. Roese was slightly wounded on July 29, 1918. The date of his discharge was March 11, 1919.

Roese and his brothers were in their father’s household in the 1920 census. They resided in the Bronx at 1303 Findlay Avenue. Roese was unemployed.

The New York, New York Marriage Index at Ancestry.com said Roese married on June 23, 1923.

Roese, his wife, Irene, and daughter, Louise, were listed in the 1925 state census at 124 Fort George Avenue in Manhattan, New York City. Roese’s occupation was artist. In the book, Biographical Sketches of Cartoonists & Illustrators in the Swann Collection of the Library of Congress, Sara Duke said Roese was a partner in the Goesle-Roese Studio.

1927

Brooklyn Daily Eagle 10/25/1932

A 1933 New York city directory listing had Roese’s home at Randall Manor in Staten Island, and his studio in Manhattan at 154 East 37th Street, on the fifth floor.

Roese took his family on a cruise in 1935. His home address was 51 Conyingham, Staten Island.

Commercial artist Roese was a lodger at 154 East 37th Street in Manhattan at the time of the 1940 census. City directories from 1942 to 1946 had him at 151 East 37th Street.

Life magazine published Roese’s drawings on three occasions: First Road to Ruin, August 7, 1939; This Is a Day in Babe’s Life, April 21, 1941; and Blithe Spirit, October 22, 1945.

Roese illustrated several books including Topper (1926), Topper Takes a Trip (1932), The Merry Mixer or Cocktails and Their Ilk (1933), Rain in the Doorway (1933), The Glorious Pool (1937), The Passionate Witch (1941), All-Out Arlene (1943) and Bats in the Belfry (1943).

—Alex Jay

Labels: Ink-Slinger Profiles

Tuesday, February 16, 2016

Ink-Slinger Profiles by Alex Jay: Garrett Price

In 1910, Price, his father and brother still lived in Saratoga. The New York Times, April 10, 1979, said Price grew up on a farm and sketched animals and people at a young age.

Price attended the University of Wyoming in Laramie. At least 16 illustrations by Price appeared in the 1913 yearbook, The Wyo (see pages 51, 59, 67, 73, 82, 101, 105, 108, 148, 186, 190, 194, 195, and 197). Price was a member of the Pen Pushers, an honorary journalistic society. The following year, Price contributed 15 illustrations to The Wyo. He was still a member of the Pen Pushers and chairman of the publicity committee of the Young Men’s Christian Association. In the 1915 Wyo, Price continued his chairmanship and was a pledge at the fraternity, Sigma Beta Phi.

1914

Agnes Wright Spring wrote about Price in her book, Near the Greats (1981):

Garrett Price attended the University of Wyoming and drew the little sketches for the WYO, the Junior Annual, which I edited.The Times said Price attended the Chicago Art Institute where he met future New Yorker magazine artists Perry Barlow, Alice Harvey and Helen Hokinson. Price “began his career as reporter-cartoonists for The Kansas City Star.”

As I remember him then, he was only a freshman. He was small and wore knee breeches. But we all recognized his drawing talent and sought his help with the WYO.

Later I saw Garrett when he was doorkeeper of the Senate during the Wyoming Legislature, when I was State Librarian.

Garrett Price left Wyoming to attend the Art Institute in Chicago and from there became a reporter-cartoonist for the Kansas City Star….

While at the Chicago Tribune, Price was in baseball game between the artists of the Tribune and the Herald. Price’s teammates were John T . McCutcheon, Ring Lardner, Sidney Smith, Dom C. Lavin, Garrett Price, Bob Blake, O.G. Lundberg, Henry Koropp, William Donahey, Carry Orr, Raymond Mehrens, Frank King, Herbert Stoops, Cyrus Foy, and Raymond Sissly. On the Herald team were E.C. Segar, Bud Willard, D. McCarthy, Hugh Cash, Bill Wisner, Armand Fournier, Alex. DeBeck, Ben Cohen, George Lundy, Louis Chicoine, L.O. Butcher, Bill Willard, Lyman Atwell. The Tribune, May 23, 1917, reported the upcoming game to benefit the Red Cross.

The Times said that during World War Price contributed drawings to Navy publications. Sara Duke, in Biographical Sketches of Cartoonists & Illustrators in the Swann Collection of the Library of Congress (2012), said Price was a news illustrator for the Great Lakes Navy Bulletin.

Price signed his World War I draft card on May 29, 1918. His address was 4321 Champlain Avenue in Chicago and his employer was the Tribune. He named his father as his nearest relative. Price was described as medium height, slender build with blue eyes and light brown hair. On July 9, 1918, the Tribune reported Price’s enlistment.

Garrett Price, for two years a member of The Tribune art staff, yesterday enlisted in the navy and immediately began his training at Great Lakes. Mr. Price is a native of Wyoming, but came to Chicago several years ago to study at the Art Institute. He became a member of The Tribune staff shortly after completing his studies at the institute and soon became one of the staff illustrators. Mr. Price is the 211th Tribune employe to go into his country’s service, and the fifth member of the art staff to enlist.Price’s address and employer were the same in the 1920 census. Price was a roomer in the Spitzig household. About six months after the census, Price was mentioned in the Fourth Estate, July 31, 1920: “Garrett Price of the art staff of the Chicago Tribune is in the Michigan lake region on his vacation.”

In the mid-1920s, Price moved to New York City. Duke said Price was “a regular contributor to Harper’s Bazaar, Scribner’s, Stage, Collier’s, College Humor, Esquire and other leading magazines.” Price is perhaps best known for his cover artwork for the New Yorker magazine from 1925 to 1974.

Price married Florence Semler in 1928. They visited Europe. Aboard the S.S. Carmania, the couple departed Havre, France, on June 7, 1928 and arrived in New York City on July 16. Their address was 2 East 12th Street in New York City.

The 1930 census recorded Price and his wife, Florence, in Manhattan, New York City, at 308 West 8th Street. He was a freelance commercial artist.

In March 1931 Price and Florence sailed to Hamilton, Bermuda, which was her birthplace as recorded on the passenger list.

American Newspaper Comics (2012) said Price produced White Boy in Skull Valley, for the Tribune then the New York News Syndicate. The strip ran from October 1, 1933 to August 30, 1936. The topper was Funny Fauna which started October 20 or 27, 1935. (White Boy has been published as a book by Sunday Press and was reviewed here.)

In the 1940 census, freelance cartoonist Price resided at 1 University Place in Manhattan.

On April 27, 1942, Price signed his World War II draft card. His residence was 393 Kings Highway in Fairfield, Connecticut. He was self-employed, five feet five-and-a-half inches tall, 132 pounds and had blue eyes and brown hair.

During July 1940, the “Wish you were here” advertisements, for New York Telephone, featured Price’s artwork. According to American Newspaper Comics, Price was one of several artist who drew the Calvert Reserve Whisky advertising panel, Metropolitan Moments, which ran in the 1940s.

Long Island Daily Press 7/24/1940

In 1946 a collection of Price’s cartoons was published in Drawing Room Only. Price illustrated David Stern’s book, Francis, which was published by Farrar, Straus & Co. in 1946.

During the 1950s and 1960s, city directories listed Price in Westport, Connecticut.

Price passed away April 8, 1979, in Norwalk, Connecticut, according to the Connecticut Death Index. Obituaries appeared in many publications including the Times, The Day and the Toledo Blade.

—Alex Jay

Labels: Ink-Slinger Profiles

Comments:

He also drew three books written by Mary Nash:

While Mrs. Coverlet Was Away (1958)

Mrs. Coverlet's Magicians (1961)

Mrs. Coverlet's Detectives (1965)

Post a Comment

While Mrs. Coverlet Was Away (1958)

Mrs. Coverlet's Magicians (1961)

Mrs. Coverlet's Detectives (1965)

Monday, February 15, 2016

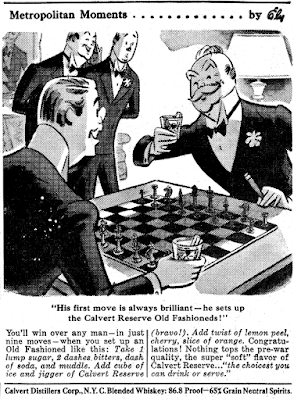

Advertising Features: Metropolitan Moments

When the U.S. entered World War II there came a pressing need for alcohol in various industrial capacities. Therefore the government curtailed much of the private alcohol production for human consumption. Luckily there was no immediate danger of running out of spirits entirely, because Ireland was still producing and exporting whiskey, and many American liquor companies, reading the writing on the wall, had reserved quite a bit of their production for just such a situation.

The smartest distillers stockpiled not whiskeys, rums, and other specific spirits, but instead created stores of 'neutral spirits' -- grain alcohol -- which they could use to blend with smaller stockpiles of American whiskeys and imported Irish spirits. What was produced was then termed a 'blend', and while it was universally reviled as rotgut, well, beggars can't be choosers, and so Americans held their noses, lived with pounding headaches the morning after, and kept on drinking.

Spirits were advertised heavily during the war, generally with the marketing hype trying to convince buyers that their brand was just as good as the pre-war stuff -- which of course it wasn't. Calvert was on that bandwagon, and they came up with a long-term newspaper campaign for Calvert Reserve Blended Whiskey that interests us here on Stripper's Guide. Starting in January 1942, they inaugurated a series titled Metropolitan Moments, featuring cartoons by some of the leading lights of the magazine gag cartoon world.

In the samples above, you see a roughly chronological sampling of the Metropolitan Moments ad campaign. We start with Jaro Fabry, the great magazine 'pretty girl' cover artist, who provided almost all of the cartoons through about September 1942. Then he disappeared, and the panel was taken over by someone pseudonymously identified as "Wisdom". Wisdom's work is sort of generic New Yorker style of the day, with elements of William Steig, Charles Addams and Peter Arno. Would love it if someone could offer a positive ID on this fellow.

"Wisdom" was credited with all of the panels through 1944, then the byline changed to "Ely". Ely's work sure looks a lot like Wisdom's to me, so I'm not sure why the credit was changed. The main difference I do see is that Ely had a fondness for a clubby, tuxedoed older gentleman who became a regular in the cartoons during his tenure.

In 1945, the panel got much more interesting. All of a sudden there were other cartoonists contributing, mostly really high-end New Yorker level folks. I've found panels by Abner Dean, Chon Day and Garrett Price, as well as a lesser known fellow named Herbert Roese, and someone with whom I'm unfamiliar, who went by the moniker H. Williamson. The new star of the show, though, was the great Richard Taylor, who produced far more of the panels than anyone else.

The panel finally stopped appearing in May 1947 after a five and a half year run. In some papers the panels appeared almost daily, others got them much less often. However, don't take that to mean that somehow the cartoonists came up with 300-odd different gags concerning Calvert Reserve Whiskey each year. The panels were definitely re-used, though based on my own collection there sure were a lot of different panels to choose from -- definitely in the realm of the hundreds.

Labels: Advertising Strips

Comments:

I have Taylor's book on cartooning. It's wonderful. It's fun to see his work in this advertising medium.

Post a Comment