Saturday, February 29, 2020

What the Cartoonists are Doing, February 1916 (Vol.9 No.2)

[Cartoons Magazine, debuting in 1912, was a monthly magazine

devoted primarily to reprinting editorial cartoons from U.S. and foreign

newspapers. Articles about cartooning and cartoonists often

supplemented the discussion of current events.

In November 1913 the magazine began to offer a monthly round-up of news about cartoonists and cartooning, eventually titled "What The Cartoonist Are Doing." There are lots of interesting historical nuggets in these sections, and this Stripper's Guide feature will reprint one issue's worth each week.]

RAEMAEKERS’ LONDON DEBUT

The reputation of Louis Raemaekers, the Dutch cartoonist, has been made in London almost overnight. A month ago he was virtually unknown in the British metropolis. Today everybody is flocking to the galleries of the Fine Art Society to see his war cartoons, the most terrible satires, perhaps, that have thus far been produced on the perpetrators of the world war.

Writing on the art of Raemaekers, the New York Herald's London correspondent Says:

“That Mr. Raemaekers is a born satirist with the pencil is granted. When he makes a point in a picture there can be no doubt about his meaning, and he makes it entirely in the picture and not in the words written underneath it. He draws his thoughts and feelings, giving to them visible shape and substance. The Kaiser in his satire is not only the Kaiser himself to the life; he is also an idea of the Kaiser and of what he represents. And his German soldiers are soldiers, but they are also German militarism in the flesh.

“When he chooses he can draw an allegory, as in a cartoon where swine fatten upon the dead body of Edith Cavell. And one of the swine has an iron cross tied to his tail, an example which shows that he has all the fierce indignation of the French cartoonists, while it is with him, as with the greatest of them, imaginative ferocity, not scurrility. It is like lightning striking baseness from a great height.

“Lately he has turned to Ferdinand of Bulgaria with almost an ecstasy of contempt. He has created a figure of the Balkan Fox as the French cartoonists created one of Louis Philippe, a figure in which his whole policy and his whole character seem to be visible.

“And be it remembered Mr. Raemaekers is not a partisan. He is a Dutchman, and impartial, possessing only the warmth of a judge who has seen the crime committed. There is no reason in his nationality, in his temperament, in his education why he should be against the Germans. In Holland Mr. Raemaekers always carries a revolver, and always is receiving threatening letters from Germans. If they could only catch him over the frontier by a mere yard there would be no more cartoons from Louis Raemaekers.

“The Dutch are proud of him, for he says with his pencil what they all feel, even when his satire is turned against his own people. He sometimes turns his satire against England, but England only laughs at herself with him. Mr. Raemaekers has noted while he has been in London the free bearing of the British soldiers as they walk the streets, compared with the German servile arrogance. In them Britain expresses herself to him and tells him what she is fighting for, and he, with his pencil, is fighting for the same righteous cause.”

CARTOONISTS AND CLASS HATRED

From the Buffalo Evening News

We venture the guess that Americans are getting more closely to the roots of things. For example, a significant thing happened in Philadelphia. The American Society for the Promotion of Citizenship denounced the cartoonists of America for being chief contributors to class hatred.

The denunciation is merited. Not that cartoonists are a bomb-throwing, shell dropping tribe. Not at all; they are, on the contrary, mild, meek and quite harmless. We know some of them who carry their handkerchiefs in their sleeves.

They do, however, err in common with the average professional humorist. They underestimate the force of their own lines.

The Philadelphia society generalized— was sweeping in its indictment—which is a sufficient excuse for specifying.

Among the worst offenders is Opper, a cartoonist who has honestly pleased two generations of people, but whose silly caricature of the common people has never increased national self-respect and has done as much as any agency to create, promote and nourish class hatred.

In these days of such keen competition the individual is apt to designate the caprices of fortune, the ends of injustice and all other inequalities of life by the ridiculous symbol made familiar by Opper.

It isn't healthy.

We shall welcome the cartoonist who will picture the common people with a strong, sturdy figure, tied and gagged by traditions and usages, perhaps, but still strong and giving promise of rending those bonds that bind.

MYERS’ “BLOODLESS” COMIC

Fred Myers of Indianapolis has evolved a “bloodless” comic, which he plans to introduce to an expectant public. “By this,” he says, “I mean seeking the psychological ‘punch' without recourse to brickbats and rough stuff. I figure it out this way: it isn’t funny to see a man slammed with a brick in real life—so why should it be so in pictures?

“My neighbors have honored me by laughing at the drawings, so when I think of what a time Columbus had before he put it over, I begin to take heart.”

Mr. Myers will be remembered for his cartoons published in connection with the recent political scandal in Terre Haute.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

“I’ve been waiting to see the cartoonist for two hours,” said the caller in the newspaper office.

“He’s upstairs in the office, trying to draw,” replied a passing reporter.

“Trying to draw?”

“Yes, he's trying to draw his salary.”— Yonkers Statesman.

CENTRAL NEW YORK ART LEAGUE HOLDS SUCCESSFUL EXHIBIT

The Central New York Art League has received many congratulations on the success of its first annual exhibition, which closed in Syracuse on January 1. D. Darian, cartoonist of the Syracuse Post-Standard, and president of the league, selected as judges, C. A. Voight of the Central Press Association, Vic Lambdin of the Syracuse Herald, and several New York newspaper artists. More than 300 drawings in pen and ink, charcoal, oils, and watercolors were shown, and many artists and cartoonists of national fame were represented. Among these were “Bud” Fisher, of Mutt and Jeff fame; George Herriman, originator of the “Dingbats”; C. A. Voight, father of “Petey Dink”; J. K. Bryan, a silhouette specialist; George McManus, producer of “The Newlyweds,” and “Panhandle Pete”; Gene Carr, originator of “Lady Bountiful” , Kate Carew, a well-known caricaturist; “Tad,” T. E. Powers and Rube Goldberg. A number of drawings by Phil Porter, who was found dead near Chicago several weeks ago, were draped in mourning.

FAREWELL

Upon the far horizon's rim

The Peace ship slowly fades from sight.

Good-bye to Hen, good luck to him.

But, oh, those dreams of peace — “Good Night!”

–Nelson Harding, in Brooklyn Eagle.

KEENE A LIEUTENANT NOW

Louis Keene, cartoonist of Beck's Weekly, Montreal, marched away in August, 1914, with the Maple Leaf boys. He is back home now with his right hand smashed, but with a lieutenant’s commission.

A piece of high-explosive shell, at Ypres, did the damage—after Lieutenant Keene had served for exactly a year. He was sent home, where he immediately began learning to draw with his left hand. So rapid was his progress that he resumed his cartoon work for Beck's Weekly, and even managed to paint a couple of war pictures for a recent exhibit. He received his commission in England, and was promoted in Belgium, and now he expects to return to the front again with one of the new battalions. Lieutenant Keene says that Cartoons Magazine was greatly enjoyed in the trenches.

HARRY S. OSBORN'S DEATH

The death was announced on December 7, 1915, of Harry S. Osborn, cartoonist of the Richmond Times-Dispatch. Mr. Osborn's death occurred at the home of his father in Darlington, Wis., and was due to a nervous breakdown. Mr. Osborn did his best work on the Baltimore News. A series of drawings used in a church crusade in Baltimore added to his reputation in that city. Later he contributed cartoons to the Maryland Suffrage News. Mr. Osborn's work is familiar to readers of Cartoons Magazine. His rather peculiar style of line drawing imparted to his work a certain personality and distinction.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Lee Stanley's cartoon, “The Porkless Menu,” which was copied extensively in the United States and Europe, caught the eye of Congressman F. C. Hicks, of the Long Island district, who has had the original framed for his office. Mr. Stanley took Bushnell's place on the Central Press Association of Cleveland.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

HANNY “LOOKS BACKWARD”

“Looking Backward” is the title of a new cartoon book by W. Hanny, of the St. Joseph News-Press. The volume contains 96 cartoons selected from the file of the News-Press. Many of these have been reproduced in other newspapers and magazines. Some of the pictures call back early days of boyhood—notably one entitled “Your First Smoke,” depicting a small boy in bed, while a worried mother and a rather amused father stand beside him.

CARTOON LIFE IN MEXICO

To the Editor: Mr. Dunn's article in your January issue, on the present-day Mexican cartoonists and their opinions of Carranza, was of especial interest to me as the one-time cartoonist of El Diario of Mexico City. Heartily I echo their sentiments regarding the “first chief,” and “muchly” do I admire their courage, for cartooning in Mexico is not one of the “preferred occupations” according to the life insurance agents.

Before the Madero revolution, when Don Porfirio held the reins, the political cartoonist was strictly persona non grata in the eyes of the authorities. I know of one case, that of an art student who had assimilated some socialistic ideas in Paris, and who started to turn the Mexican capital inside out by publishing a weekly, bearing the euphonious title of El Tlin Tlin. There were four pages of it—printed in red ink— the front and back filled with caricatures of the powers that were, and the “innards” containing undiluted opinions of the lampooned dignitaries. Three issues appeared, and then the artist disappeared. After a lapse of several months the Alameda and the Zocolo reëchoed again to the sound of the newsies crying “Tlin Tlin,” for the crusader had come back. True, his cheeks were hollower, his hair considerably shorter and his general color scheme hinted strongly of prison pallor, but in no wise was his determination altered. For two Saturdays in succession he labored (for be it understood, he possessed a pull) and then history repeated itself; the pull failed, and this time he did not return.

At about that time the rurales (mounted rangers) were making another Belgium of Sonora, in the Yaqui district, and several shipments of captured Indians were sent through the city to slavery in the South. The barbarism with which they were treated reminded me of the tales of the days of Montezuma and the bloody sacrifices of the Aztec priesthood to Huitzilopoctli (the war god). With the aid of Muniz, the director of El Diario, I framed a cartoon depicting the rites of the sacrifice, with a Yaqui as the offering, a prominent minister playing the executioner and Don Porfirio himself as the war god! During the absence of Senor Simondetti, the editor, we “put it over,” but the censor caught it before the ink was dry, and Muniz went to Cuba (between two suns). I left the city in a laundry basket, in a Wells Fargo car, on a hurry-up trip for the border line and a haven in God's country.

Since that memorable occasion I have been in Mexico several times, along the border during the first revolution, sketching the insurrectos or selling soap and perfume to the noncombatants.

“The lure of the little voices” ofttimes calls me to return to the land of mañana, and I would like nothing better than to add the scratch of my pen to the general chorus of criticisms of Carranza, but I cannot—for my wife won’t let me; she says that she has no desire to collect on the policy of ---

RALPH. C. FAULKNER.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Hansi, whose cartoon book, “Mon. Village,” so angered the German authorities that they, sentenced him to prison, is now an interpreter in the French army. He has been decorated with the cross of the Legion of Honor.

THE NERVE OF CARTOONISTS

Cartoonists seem to be people of nerve. John McCutcheon has pierced darkest Africa, Boardman Robinson is making war pictures at the most dangerous parts of the front, and H. T. Webster, whose cartoons were recently published in book form under the name of “Our Boyhood Thrills,” accompanied George A. Dorsey, curator of the Field Columbian Museum of Chicago, on one of the most perilous trips ever made by white men. They went up the Yangtse River through rapids so dangerous that it was like passing Niagara every day, and they nearly reached the border of the Tibet, through a part of China which no white man has ever seen before or since.— New York Globe.

GOLDBERG CARTOON SALE

A sale of Goldberg originals was held during the holidays at the American Art Galleries, New York, for the benefit of the New York Evening Mail’s “Save-a-Home” fund. The cartoons were auctioned off by Thomas E. Kirby, of the American Art Association, and his assistant, Otto Bernet.

THE VOICE OF THE AMATEUR

To the Editor:

Relative to the first paragraph in Helena Smith-Dayton's article, “Many are Called, but Few are Chosen,” in your January number, why are we amateurs called “fame chasers”? “Some not yet escaped from art schools,” she says! (And some who never saw an art school.) Some of us are timid, others overconfident, but all desirous of be coming Ethel Plummers or James Montgomery Flaggs, May Wilson Prestons, or Ralph Bartons! Why, almost anyone would have such a desire if he were interested in art—or to do work like Mrs. Dayton.

If time would turn back in its flight, I am sure we could see all these, and other present-day celebrities, in the ranks of so called fame chasers. Because of this I am sure that many of us will someday become fully as great as the least of the now famous. Miss Plummer's work does not need a slap at the amateurs to enhance its worth–nor do the fame chasers need it to spur them on.

H.A. Daake

Lima, Ohio.

P. S.—Have just landed a job on the local paper. Look for some of my work in the next mail.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

A course in cartooning and caricature has been opened at the University of Notre Dame in connection with the department of journalism.

PRESS ARTISTS EXHIBIT

The recent exhibition of the St. Louis newspaper artists at the St. Louis Press Club, which was extended because of its popularity, closed December 13, 1915. One hundred and twenty pictures were shown, including oil paintings, watercolors, crayon, and pen and ink sketches. Among the artists represented were A. Russell, R. J. Bieger, Arthur L. Friedrich, George Grinham and Percy Vogt, of the Globe-Democrat; Arthur Button, Gus T. Coleman and A. B. Chapin, of the Republic; Miss Juanita Hamel and Elmer Pins, of the Times; Frederick Tuthill, of the Star, and D. R. Fitzpatrick, of the Post-Dispatch.

WESTERMAN AS A PORTRAIT ARTIST

“The worst thing about telling a whopper,” says the Ohio State Journal, “is that one leads on to more, and you soon get so that you can’t tell the truth at all. Here, for instance, is the Chicago Tribune, which for some time has been pretending to be the world's greatest newspaper, and which, having formed the habit, now announces that it has on its staff the world’s greatest portrait artist, although the individual in question can’t hold a candle to Mr. Westerman, in spite of the latter's excess of artistic temperament.”

The Tribune's new portrait artist, it might be interesting to know, is Frank Wing, author of the Fotygraft Album, and for many years head of the Minneapolis Journal's art staff. Mr. Wing is now in Washington for the Tribune, making sketches of the senators and congressmen. The accompanying sketch of President Wilson in three moods by Mr. Westerman may possibly uphold the State Journal's contention.

CARTOONISTS AID CHARITY

Quite a galaxy of cartoonists offered their services for the recent benefit performance given at the Hippodrome by the New York American.

R. F. Outcault drew some new pictures of Buster Brown and Mary Jane; T. E. Powers created more of his “Glooms and Joys”; Harry Hershfield showed “Abie the Agent,” and George McManus, Tad, Cliff Sterrett, James Swinnerton, F. Opper, Harold H. Knerr and Tom McManus each did something in his own line. Winsor McCay had the hardest part of all. He was billed as “the world's greatest cartoonist.”

At the St. Mark's bazaar at the Grand Central Palace, a cartoon by Cesare, of the New York Sun, was purchased by Gouverneur Morris for $200.

In November 1913 the magazine began to offer a monthly round-up of news about cartoonists and cartooning, eventually titled "What The Cartoonist Are Doing." There are lots of interesting historical nuggets in these sections, and this Stripper's Guide feature will reprint one issue's worth each week.]

RAEMAEKERS’ LONDON DEBUT

The reputation of Louis Raemaekers, the Dutch cartoonist, has been made in London almost overnight. A month ago he was virtually unknown in the British metropolis. Today everybody is flocking to the galleries of the Fine Art Society to see his war cartoons, the most terrible satires, perhaps, that have thus far been produced on the perpetrators of the world war.

Writing on the art of Raemaekers, the New York Herald's London correspondent Says:

“That Mr. Raemaekers is a born satirist with the pencil is granted. When he makes a point in a picture there can be no doubt about his meaning, and he makes it entirely in the picture and not in the words written underneath it. He draws his thoughts and feelings, giving to them visible shape and substance. The Kaiser in his satire is not only the Kaiser himself to the life; he is also an idea of the Kaiser and of what he represents. And his German soldiers are soldiers, but they are also German militarism in the flesh.

“When he chooses he can draw an allegory, as in a cartoon where swine fatten upon the dead body of Edith Cavell. And one of the swine has an iron cross tied to his tail, an example which shows that he has all the fierce indignation of the French cartoonists, while it is with him, as with the greatest of them, imaginative ferocity, not scurrility. It is like lightning striking baseness from a great height.

“Lately he has turned to Ferdinand of Bulgaria with almost an ecstasy of contempt. He has created a figure of the Balkan Fox as the French cartoonists created one of Louis Philippe, a figure in which his whole policy and his whole character seem to be visible.

“And be it remembered Mr. Raemaekers is not a partisan. He is a Dutchman, and impartial, possessing only the warmth of a judge who has seen the crime committed. There is no reason in his nationality, in his temperament, in his education why he should be against the Germans. In Holland Mr. Raemaekers always carries a revolver, and always is receiving threatening letters from Germans. If they could only catch him over the frontier by a mere yard there would be no more cartoons from Louis Raemaekers.

“The Dutch are proud of him, for he says with his pencil what they all feel, even when his satire is turned against his own people. He sometimes turns his satire against England, but England only laughs at herself with him. Mr. Raemaekers has noted while he has been in London the free bearing of the British soldiers as they walk the streets, compared with the German servile arrogance. In them Britain expresses herself to him and tells him what she is fighting for, and he, with his pencil, is fighting for the same righteous cause.”

CARTOONISTS AND CLASS HATRED

From the Buffalo Evening News

We venture the guess that Americans are getting more closely to the roots of things. For example, a significant thing happened in Philadelphia. The American Society for the Promotion of Citizenship denounced the cartoonists of America for being chief contributors to class hatred.

The denunciation is merited. Not that cartoonists are a bomb-throwing, shell dropping tribe. Not at all; they are, on the contrary, mild, meek and quite harmless. We know some of them who carry their handkerchiefs in their sleeves.

They do, however, err in common with the average professional humorist. They underestimate the force of their own lines.

The Philadelphia society generalized— was sweeping in its indictment—which is a sufficient excuse for specifying.

Among the worst offenders is Opper, a cartoonist who has honestly pleased two generations of people, but whose silly caricature of the common people has never increased national self-respect and has done as much as any agency to create, promote and nourish class hatred.

In these days of such keen competition the individual is apt to designate the caprices of fortune, the ends of injustice and all other inequalities of life by the ridiculous symbol made familiar by Opper.

It isn't healthy.

We shall welcome the cartoonist who will picture the common people with a strong, sturdy figure, tied and gagged by traditions and usages, perhaps, but still strong and giving promise of rending those bonds that bind.

MYERS’ “BLOODLESS” COMIC

Fred Myers of Indianapolis has evolved a “bloodless” comic, which he plans to introduce to an expectant public. “By this,” he says, “I mean seeking the psychological ‘punch' without recourse to brickbats and rough stuff. I figure it out this way: it isn’t funny to see a man slammed with a brick in real life—so why should it be so in pictures?

“My neighbors have honored me by laughing at the drawings, so when I think of what a time Columbus had before he put it over, I begin to take heart.”

Mr. Myers will be remembered for his cartoons published in connection with the recent political scandal in Terre Haute.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

“I’ve been waiting to see the cartoonist for two hours,” said the caller in the newspaper office.

“He’s upstairs in the office, trying to draw,” replied a passing reporter.

“Trying to draw?”

“Yes, he's trying to draw his salary.”— Yonkers Statesman.

CENTRAL NEW YORK ART LEAGUE HOLDS SUCCESSFUL EXHIBIT

The Central New York Art League has received many congratulations on the success of its first annual exhibition, which closed in Syracuse on January 1. D. Darian, cartoonist of the Syracuse Post-Standard, and president of the league, selected as judges, C. A. Voight of the Central Press Association, Vic Lambdin of the Syracuse Herald, and several New York newspaper artists. More than 300 drawings in pen and ink, charcoal, oils, and watercolors were shown, and many artists and cartoonists of national fame were represented. Among these were “Bud” Fisher, of Mutt and Jeff fame; George Herriman, originator of the “Dingbats”; C. A. Voight, father of “Petey Dink”; J. K. Bryan, a silhouette specialist; George McManus, producer of “The Newlyweds,” and “Panhandle Pete”; Gene Carr, originator of “Lady Bountiful” , Kate Carew, a well-known caricaturist; “Tad,” T. E. Powers and Rube Goldberg. A number of drawings by Phil Porter, who was found dead near Chicago several weeks ago, were draped in mourning.

FAREWELL

Upon the far horizon's rim

The Peace ship slowly fades from sight.

Good-bye to Hen, good luck to him.

But, oh, those dreams of peace — “Good Night!”

–Nelson Harding, in Brooklyn Eagle.

KEENE A LIEUTENANT NOW

Louis Keene, cartoonist of Beck's Weekly, Montreal, marched away in August, 1914, with the Maple Leaf boys. He is back home now with his right hand smashed, but with a lieutenant’s commission.

A piece of high-explosive shell, at Ypres, did the damage—after Lieutenant Keene had served for exactly a year. He was sent home, where he immediately began learning to draw with his left hand. So rapid was his progress that he resumed his cartoon work for Beck's Weekly, and even managed to paint a couple of war pictures for a recent exhibit. He received his commission in England, and was promoted in Belgium, and now he expects to return to the front again with one of the new battalions. Lieutenant Keene says that Cartoons Magazine was greatly enjoyed in the trenches.

HARRY S. OSBORN'S DEATH

The death was announced on December 7, 1915, of Harry S. Osborn, cartoonist of the Richmond Times-Dispatch. Mr. Osborn's death occurred at the home of his father in Darlington, Wis., and was due to a nervous breakdown. Mr. Osborn did his best work on the Baltimore News. A series of drawings used in a church crusade in Baltimore added to his reputation in that city. Later he contributed cartoons to the Maryland Suffrage News. Mr. Osborn's work is familiar to readers of Cartoons Magazine. His rather peculiar style of line drawing imparted to his work a certain personality and distinction.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Lee Stanley's cartoon, “The Porkless Menu,” which was copied extensively in the United States and Europe, caught the eye of Congressman F. C. Hicks, of the Long Island district, who has had the original framed for his office. Mr. Stanley took Bushnell's place on the Central Press Association of Cleveland.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

HANNY “LOOKS BACKWARD”

“Looking Backward” is the title of a new cartoon book by W. Hanny, of the St. Joseph News-Press. The volume contains 96 cartoons selected from the file of the News-Press. Many of these have been reproduced in other newspapers and magazines. Some of the pictures call back early days of boyhood—notably one entitled “Your First Smoke,” depicting a small boy in bed, while a worried mother and a rather amused father stand beside him.

CARTOON LIFE IN MEXICO

To the Editor: Mr. Dunn's article in your January issue, on the present-day Mexican cartoonists and their opinions of Carranza, was of especial interest to me as the one-time cartoonist of El Diario of Mexico City. Heartily I echo their sentiments regarding the “first chief,” and “muchly” do I admire their courage, for cartooning in Mexico is not one of the “preferred occupations” according to the life insurance agents.

Before the Madero revolution, when Don Porfirio held the reins, the political cartoonist was strictly persona non grata in the eyes of the authorities. I know of one case, that of an art student who had assimilated some socialistic ideas in Paris, and who started to turn the Mexican capital inside out by publishing a weekly, bearing the euphonious title of El Tlin Tlin. There were four pages of it—printed in red ink— the front and back filled with caricatures of the powers that were, and the “innards” containing undiluted opinions of the lampooned dignitaries. Three issues appeared, and then the artist disappeared. After a lapse of several months the Alameda and the Zocolo reëchoed again to the sound of the newsies crying “Tlin Tlin,” for the crusader had come back. True, his cheeks were hollower, his hair considerably shorter and his general color scheme hinted strongly of prison pallor, but in no wise was his determination altered. For two Saturdays in succession he labored (for be it understood, he possessed a pull) and then history repeated itself; the pull failed, and this time he did not return.

At about that time the rurales (mounted rangers) were making another Belgium of Sonora, in the Yaqui district, and several shipments of captured Indians were sent through the city to slavery in the South. The barbarism with which they were treated reminded me of the tales of the days of Montezuma and the bloody sacrifices of the Aztec priesthood to Huitzilopoctli (the war god). With the aid of Muniz, the director of El Diario, I framed a cartoon depicting the rites of the sacrifice, with a Yaqui as the offering, a prominent minister playing the executioner and Don Porfirio himself as the war god! During the absence of Senor Simondetti, the editor, we “put it over,” but the censor caught it before the ink was dry, and Muniz went to Cuba (between two suns). I left the city in a laundry basket, in a Wells Fargo car, on a hurry-up trip for the border line and a haven in God's country.

Since that memorable occasion I have been in Mexico several times, along the border during the first revolution, sketching the insurrectos or selling soap and perfume to the noncombatants.

“The lure of the little voices” ofttimes calls me to return to the land of mañana, and I would like nothing better than to add the scratch of my pen to the general chorus of criticisms of Carranza, but I cannot—for my wife won’t let me; she says that she has no desire to collect on the policy of ---

RALPH. C. FAULKNER.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Hansi, whose cartoon book, “Mon. Village,” so angered the German authorities that they, sentenced him to prison, is now an interpreter in the French army. He has been decorated with the cross of the Legion of Honor.

THE NERVE OF CARTOONISTS

Cartoonists seem to be people of nerve. John McCutcheon has pierced darkest Africa, Boardman Robinson is making war pictures at the most dangerous parts of the front, and H. T. Webster, whose cartoons were recently published in book form under the name of “Our Boyhood Thrills,” accompanied George A. Dorsey, curator of the Field Columbian Museum of Chicago, on one of the most perilous trips ever made by white men. They went up the Yangtse River through rapids so dangerous that it was like passing Niagara every day, and they nearly reached the border of the Tibet, through a part of China which no white man has ever seen before or since.— New York Globe.

GOLDBERG CARTOON SALE

A sale of Goldberg originals was held during the holidays at the American Art Galleries, New York, for the benefit of the New York Evening Mail’s “Save-a-Home” fund. The cartoons were auctioned off by Thomas E. Kirby, of the American Art Association, and his assistant, Otto Bernet.

THE VOICE OF THE AMATEUR

To the Editor:

Relative to the first paragraph in Helena Smith-Dayton's article, “Many are Called, but Few are Chosen,” in your January number, why are we amateurs called “fame chasers”? “Some not yet escaped from art schools,” she says! (And some who never saw an art school.) Some of us are timid, others overconfident, but all desirous of be coming Ethel Plummers or James Montgomery Flaggs, May Wilson Prestons, or Ralph Bartons! Why, almost anyone would have such a desire if he were interested in art—or to do work like Mrs. Dayton.

If time would turn back in its flight, I am sure we could see all these, and other present-day celebrities, in the ranks of so called fame chasers. Because of this I am sure that many of us will someday become fully as great as the least of the now famous. Miss Plummer's work does not need a slap at the amateurs to enhance its worth–nor do the fame chasers need it to spur them on.

H.A. Daake

Lima, Ohio.

P. S.—Have just landed a job on the local paper. Look for some of my work in the next mail.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

A course in cartooning and caricature has been opened at the University of Notre Dame in connection with the department of journalism.

PRESS ARTISTS EXHIBIT

The recent exhibition of the St. Louis newspaper artists at the St. Louis Press Club, which was extended because of its popularity, closed December 13, 1915. One hundred and twenty pictures were shown, including oil paintings, watercolors, crayon, and pen and ink sketches. Among the artists represented were A. Russell, R. J. Bieger, Arthur L. Friedrich, George Grinham and Percy Vogt, of the Globe-Democrat; Arthur Button, Gus T. Coleman and A. B. Chapin, of the Republic; Miss Juanita Hamel and Elmer Pins, of the Times; Frederick Tuthill, of the Star, and D. R. Fitzpatrick, of the Post-Dispatch.

WESTERMAN AS A PORTRAIT ARTIST

“The worst thing about telling a whopper,” says the Ohio State Journal, “is that one leads on to more, and you soon get so that you can’t tell the truth at all. Here, for instance, is the Chicago Tribune, which for some time has been pretending to be the world's greatest newspaper, and which, having formed the habit, now announces that it has on its staff the world’s greatest portrait artist, although the individual in question can’t hold a candle to Mr. Westerman, in spite of the latter's excess of artistic temperament.”

The Tribune's new portrait artist, it might be interesting to know, is Frank Wing, author of the Fotygraft Album, and for many years head of the Minneapolis Journal's art staff. Mr. Wing is now in Washington for the Tribune, making sketches of the senators and congressmen. The accompanying sketch of President Wilson in three moods by Mr. Westerman may possibly uphold the State Journal's contention.

CARTOONISTS AID CHARITY

Quite a galaxy of cartoonists offered their services for the recent benefit performance given at the Hippodrome by the New York American.

R. F. Outcault drew some new pictures of Buster Brown and Mary Jane; T. E. Powers created more of his “Glooms and Joys”; Harry Hershfield showed “Abie the Agent,” and George McManus, Tad, Cliff Sterrett, James Swinnerton, F. Opper, Harold H. Knerr and Tom McManus each did something in his own line. Winsor McCay had the hardest part of all. He was billed as “the world's greatest cartoonist.”

At the St. Mark's bazaar at the Grand Central Palace, a cartoon by Cesare, of the New York Sun, was purchased by Gouverneur Morris for $200.

Labels: What The Cartoonists Are Doing

Friday, February 28, 2020

Wish You Were Here, from J. Murry Jordan

J. Murry Jordan was known for his fine picture postcards, specializing in U.S. and Caribbean views. However, he was not above publishing cards of a more risque variety, featuring, heaven help us, stockinged ankles brazenly displayed in public. Get the smelling salts!

Normally we wouldn't debase ourselves here at Stripper's Guide by showing such smut, but in this one, which isn't even a photo, or if so is very heavily retouched, he steals Fred Opper's Alphonse and Gaston characters. So, you see, we really have no choice in the pursuit of full disclosure of cartooning history.

Labels: Wish You Were Here

Comments:

Hello Allan-

I'm sure the brazen lack of femininity on display here is just a sort of symbolic stand-in for it. I've been quite surprised what the actual French could get away with. The term "French Postcards" is a now fading one that referred to those of an erotic nature, anywhere fom unclothed girl poses to outright pornography. The most shocking part of this is, some pretty raunchy ones are found postally used!

It would seem, as no copyright citing a licence to use these characters is seen, that Mr. Jordan was helping himself to them without permission.

Post a Comment

I'm sure the brazen lack of femininity on display here is just a sort of symbolic stand-in for it. I've been quite surprised what the actual French could get away with. The term "French Postcards" is a now fading one that referred to those of an erotic nature, anywhere fom unclothed girl poses to outright pornography. The most shocking part of this is, some pretty raunchy ones are found postally used!

It would seem, as no copyright citing a licence to use these characters is seen, that Mr. Jordan was helping himself to them without permission.

Thursday, February 27, 2020

Obscurity of the Day: Danny Dumm

Harold Russell had been working for the Cincinnati Enquirer for over a decade when, in his role as sports cartoonist, he got the idea to create a mascot. He came up with Danny Dumm, who was introduced to Enquirer readers on April 13 1926. Danny started out in the standard role of a cartoon mascot, making wry comments from the corner of the day's cartoon. It wasn't long, though, before Russell decided to expand his role. On June 3 1926 he placed his first horse track bet, and from then on Russell tracked his purse, just the way that Bud Fisher had in 1907 when he created A. Mutt for the San Francisco Chronicle. Starting on June 26, Danny Dumm was awarded a regular daily comic strip adjunct that ran underneath the sports cartoon on a daily basis.

Unlike Mutt, a pretty consistent loser at the track, Danny generally held his own, and often came up smelling like a rose. And he didn't just bet on horse races, but also at the dog track and perhaps other venues as well. His good luck may have not made him quite as sympathetic character as A. Mutt, but his bets certainly did impress the gamblers, who no doubt took Danny as something of a betting oracle.

Russell's creation attracted the interest of John Dille, who in 1928 advertised Danny Dumm as a daily strip syndicated through his National Newspaper Service. It is unknown if the offering was successful, though, as I've never seen the strip appearing anywhere outside the Enquirer.

The Danny Dumm strip took occasional breaks from Russell's cartoon, especially during prime sports season, but ran pretty consistently until March 12 1932. After that his gambling purse was chronicled in a panel adjunct to the main cartoon, and eventually was dropped altogether. The character Danny Dumm was then reduced back to the role of mascot and commenter on all things sports. Russell would eventually put in over 40 years as the Enquirer's sports cartoonist.

Labels: Obscurities

Wednesday, February 26, 2020

Ink-Slinger Profiles by Alex Jay: Mazie Krebs

In the 1900 census, Krebs was the only child of John, a cattle dealer, and Mary, a German emigrant. The trio lived in St. Louis at 3816 Marine Avenue.

The 1910 census said Krebs lived with her maternal grandparents, Henry and Anna Krebs, in St. Louis at 3843 Missouri Avenue. Her grandfather worked at a cigar manufacturer.

The St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 23, 1987, said

Krebs was born in St. Louis … but spent most of her childhood traveling the country with her theatrical family. Her parents divorced when she was a baby, and her mother, aunt and uncle formed a vaudeville group. [The Post-Dispatch, August 25, 1940, said the group was The DeMonieos.]

Salt Lake Telegram 6/20/1904

Krebs and her mother lived in south St. Louis when they were not on the road. She attended grade school here, then went to Cleveland High, where she won a scholarship to the Washington University School of Fine Arts.

In the Post-Dispatch, August 25, 1940, Krebs explained how she paid for school, “I had to teach dancing at night to pay my other expenses. Carrying on two jobs became too much for me. It came to the point where I had to give up one or the other, so I gave up both.”The Hatchet, 1922 yearbook of Washington University

The 1920 U.S. Federal Census recorded Krebs as “May J Spoeri” whose parents were William, a city street inspector, and “May” Spoeri. They resided in St. Louis at 3944 Grand Avenue. Spoeri married Krebs’ mother in 1917 or 1918. William Spoeri Jr. (1887–1966), was single when he signed his World War I draft card on June 5, 1917. Son-in-law Spoeri was mentioned in the July 30, 1918, Post-Dispatch obituary of Krebs’ maternal grandfather, Henry.

According to the 1930 census, Krebs was a stenographer at a sign company. She lived with her parents in St. Louis at 5059 Rosa Avenue. Her step-father was a fireman.

Krebs explained to the Post-Dispatch, February 23, 1987, how she got into advertising and industrial design in the late 1920s.

“With a self-confidence at which I blush now, considering how fuzzy and like chicken scratches were my pen lines,” she resumed, “I took some drawings made in imitation of newspaper fashions to the art director of the advertising department of Famous-Barr. He took me in hand, drilling me on such mechanical techniques as drawing shoes, garbage pails, stepladders, until I had mastered a firm pen line. After a time, lo and behold! I was offered the job of art director of a department store in Los Angeles. I stayed there a year and came back to take a position with Taylor-Rebholz, industrial designers for whom I had done some work while, for a time, I had had a desk in a free lance commercial art studio in the Holland Building. I had done billboards, outdoor display work and there first came in contact with the Streckfus company, working on their advertisements.”Krebs accompanied the partner Rebholz to Chicago to work on the world’s fair projects.

“I got a lot of experience there in modernistic effects and stylized designing,” she went on. “Besides working on fair exhibits, I did some night club interiors, cocktail bars and murals. We continued to handle some of the Streckfus advertising account, and once when I came here to submit some ideas, I heard Capt. Joe Streckfus tell about a new boat they were building. It was The President, which was to get away from the traditional ginger bread scroll work of all other river boats. I asked to be allowed to compete with other designers on its interior. Just because he didn’t know how to say ‘no,’ Capt. Joe said for me to go ahead, although obviously he had small faith in a woman’s ability to cope with such problems as steamboats presented.

“When I brought in designs for a ballroom, powder room and a bar, Capt. Joe just looked at them and didn’t say a word. I remember I talked myself hoarse, giving him a build-up of what I had done and could do. Afterward I found my sales talk had been unnecessary. He hadn’t said anything because he had no criticisms to make. They were what he wanted and he quickly saw they were practical, for Capt. Joe knows every nit and bolt that goes into the building of a steamboat. … Capt. Joe put me under contract and, when it came to designing the Admiral [in 1936], I was called in to do the job without competition.” She laughed triumphantly. ,,,

,,, After the Admiral was finished [in 1940], Krebs went back to Chicago. She worked at a variety of design-related jobs, including ones at the Museum of Science and Industry and the Joanna Western Mills firm. She designed interiors for restaurants and candy shops and worked on retainers from several corporations. About 10 years ago she moved to California and was married [to Abe Lyon Lubfin, 1893–1978].American Newspaper Comics (2012) said Krebs drew Cindy of Hotel Royale, for the George Matthew Adams Service, from around January 1937 to January 1, 1938. Apparently the last Sunday appeared December 26, 1937.

In the 1940 census, Krebs, a self-employed commercial artist, was with her parents and step-grandfather at the same 1930 address.

Krebs passed away July 8, 1993, in Santa Clara, California. She was laid to rest at New Saint Marcus Cemetery.

Further Reading and Viewing

Chambers’ Chambers

The Steamer Admiral

—Alex Jay

Labels: Ink-Slinger Profiles

Tuesday, February 25, 2020

Obscurity of the Day: Cindy of Hotel Royale

Mazie Krebs wore a lot of hats in her life, with perhaps the most memorable one being as industrial designer. She gained some lasting fame for her flagship project, the Mississipii steamboat christened The SS President.

Not long before that, she went a whole different direction, submitting the comic strip Cindy of Hotel Royale to the George Matthew Adams Service. Mr. Adams must have been very impressed, because he supposedly offered Krebs a five year contract to produce the strip as both a daily and Sunday feature. The syndicate generally stuck to daily material, especially after a disastrous attempt at offering a preprinted Sunday section in 1935 that flopped, so Adams was really going out on a limb for this feature.

Cindy of Hotel Royale was first advertised in the 1936 Editor & Publisher Syndicate Directory, but I've never found any strips published in that year. The earliest I've seen the strip is an example above, a Sunday from the end of January 1937*. Dave Strickler's E&P index notes a start date of January 9 1937, but I don't know the source from which he got that, and that date is a Saturday, not a likely day to start a new strip.

Whatever the start date, it certainly didn't appeal to many newspaper editors. The strip is nearly impossible to find. Oddly for Adams, the daily seems even rarer than the Sunday, which is a real headscratcher for a syndicate that specialized in daily material. Weirder still, as best I can tell you seemed to need both daily and Sunday to tell a coherent story with this strip, and I have yet to find a paper that ran both. Granted, my sample size is awful small -- the aforementioned Inquirer, the Atlanta Constitution and the New Orleans Times-Picayune (the first two ran the Sundays, the latter ran dailies).

In a 1940 interview with the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Krebs had this to say about the strip:

"I rather oversold myself to Mr. Adams. He gave me a five year contract. I had ideas for years ahead but producing a strip a day and a page for the Sunday papers, proved too much for me. Mr. Adams came to town, saw the circles under my eyes, meeting the hollows in my cheeks, and obligingly released me from my contract although it was most embarrassing in view of his commitments and the fact that after a year the strip was beginning to go over big."I doubt that Adams was too attached to the strip, which was definitely not actually 'going over big.' However, I must say that it did have a winning appeal to it, both in art and writing. Why it didn't go over big is the mystery. I don't know that I would have bet as big as Adams did on it, but I can certainly see why he liked it so much.

As best I can tell, the Sunday ended on December 26 1937**, with the final installment just a sheet of paper dolls. The daily ended with Cindy sailing off into the sunset on January 1 1938***.

* Though these samples are obviously from the Philadelphia Inquirer, the online digital version of the paper, though it includes Sunday comics sections in this era, does NOT include this strip. It must have run in some other section (maybe a women's magazine section?) that did not get microfilmed.

** Source: Atlanta Constitution

*** Source: New Orleans Times-Picayune, courtesy of Alex Jay.

Labels: Obscurities

Monday, February 24, 2020

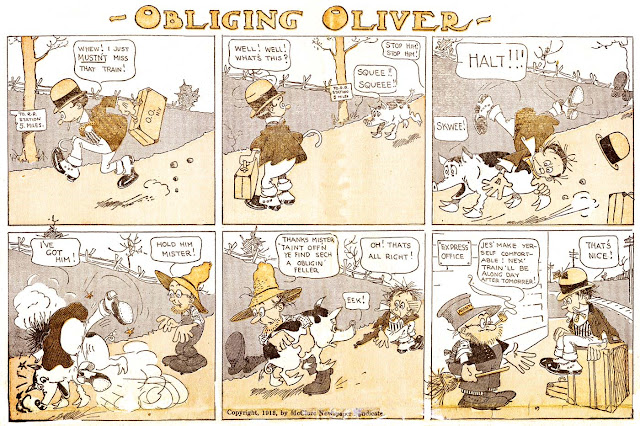

Obscurity of the Day: Obliging Oliver

Pat Sullivan would in 1919 hit the jackpot as creator of the animated cartoon phenomenon Felix the Cat, but the Australian would start off his US career in newspaper comics. After a promising but short stint in heady company at the New York World, he was demoted to working for the McClure Syndicate. There his job seems to have been to either assist or perhaps just learn to copy the work of William F. Marriner, who was undependable because of his battle with demon alcohol. In Obliging Oliver, Sullivan was obviously training himself to ape Marriner's style. The strip began on May 11 1913 with rather crude artwork, but as the series goes on the Marriner influence takes over until by the end date of April 5 1914 you can't tell Sullivan's work from that of Marriner.

That was a good thing, because it was in 1914 that Marriner died, and it seems to have been Pat Sullivan who was assigned the task of continuing the one quasi-hit McClure had left, Sambo and his Funny Noises, with Sullivan now so adept at the Marriner style that one would be hard pressed to say when the actual switch takes place.

Labels: Obscurities