Saturday, February 25, 2023

Herriman Saturday: May 19 1910

May 19 1910 -- Herriman shows his readers what they can expect for blacks if Jack Johnson wins the Fight of the Century -- they have bet big and won, so they'll be living the high life. Be with us next Herriman Saturday for the other side of the coin.

Labels: Herriman's LA Examiner Cartoons

Friday, February 24, 2023

Obscurity of the Day: Grandma Sez

When I think of Frank R. Leet, as like you I am wont to do at irregular intervals, I automatically associate him with NEA, where he produced material on the wholesale plan. But Leet also had a stopover at World Color Printing, where his most remembered contribution, if one has a memory for these sorts of things, was the rather awful Sunday strip about a pony, Duke. But today we have a daily-style panel that he produced for World Color called Grandma Sez, another in the loooong string of copycat features to Abe Martin.

For the longest time I only saw Grandma Sez in its 1920s reprint run, where it ran on WCP's weekly black and white kid's page 1928-1933. Finally, though, Francis Mouton found it in a quasi-original run in the Spokane Chronicle, where it appeared from September 28 1914 to January 7 1915. I say quasi-original becase that paper almost always ran material late and out of sequence, so the truly official dates are probably a bit earlier than those quoted here. But until someone finds WCP dailies running in a timely and orderly manner, the chances of which are pretty slim, this is the best we can do.

Labels: Obscurities

Wednesday, February 22, 2023

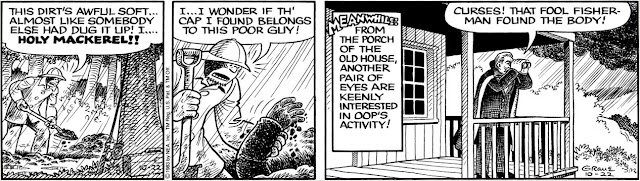

Bringing Alley Oop to a New Generation, Part 3

Chris Aruffo is producing a new extensive series of Alley Oop reprint books, a labour of love project that has presented him with many challenges. I prevailed upon him to share some of his fascinating stories about the project with Stripper's Guide readers. This essay is the final of three.

If you are interested in reading the wonderful Alley Oop strips in high-quality but reasonably priced reprints, Aruffo's books are available directly from him, through your friendly neighbourhood bookstore or comic shop, Bud Plant, or Amazon.

I wasn’t expecting to do anything at all with reprinting Sunday strips. To begin with, I didn’t feel the same affinity for the Sunday strips as I did the daily. I just didn’t know them. Throughout my life, only the dailies were ever available to me as historical archives, whether in reprint or on microform. Even though I did read and save my paper’s Sunday section from 1985–1989, these were, obviously, much more slowly paced than the exciting daily stories, so I didn’t feel as involved with them. More practically, though, I couldn’t imagine where Sunday sources would come from. The strips I’d captured during the pandemic were digitized microfilm, meaning that they were low-quality greyscale distortions of color art and thus unreprintable. While I was arranging the first twelve daily reprint books, I didn’t yet know of any resources for daily proof sheets, let alone Sundays, so I didn’t even give it a moment’s thought.

Then Rick Norwood gave that first little push to the snowball: he asked me if I wanted to restore the two Sunday Alley Oop strips for his upcoming issue of Comics Revue. I had never restored a strip before, but it seemed like fun, so I said sure, why not. In return, I didn’t want any payment; what I wanted were high-quality color images of the Sunday strips, starting with the two for restoration and going all the way back to where the two Dark Horse volumes had left off (both of which I had acquired by then). I also requested that these be the original newspaper scans and not those images which had been adjusted and resized for the Revue. Rick obligingly sent me these from his archives—and, anticipating his future needs, he also sent me all the strips to finish off 1941. I set to work on the May 18, 1941 strip.

Initially my restoration process was a very light touch. I white-balanced the page to correct for yellowing, I darkened all the lines so that anything that was supposed to be black actually was, and I adjusted any off-register spots so that colors appeared within the lines they were meant to. Everything else I left as it was.

I finished the first two strips and sent them on to Rick. Then I thought… well, why don’t I just do the next two so he’ll have them ready before his next deadline? And I might as well do another couple… and after that, well, why not two more? And now, while I’m on a roll, I might as well just finish off the year. And with those done… well, won’t it be fun to go back and restore the earlier ones as well, for my own enjoyment? And gradually, ever so gradually, it dawned on me that, if I keep this up, I will have two and a half years of restored strips, which is plenty enough to create a complete book picking up where Dark Horse left off. But I had to find out: was I too late? Was Dark Horse already planning a Volume Three? Their two books had been published six years prior, which seemed indicative, but, to be certain, I wrote to the editor of those books, Dan Chabon, who confirmed that Dark Horse had no further interest. So it could happen. Even so, I didn’t tell anyone that I was considering a Sundays book. For one, I still didn’t have all the sources I needed, because in a number of cases Rick had only the half-size strip. Mainly, though, despite still being cloistered by the pandemic, I didn’t know whether I would have the patience and the stamina for it. Even if I dedicated every scrap of my free time to the project, I could see it would still take many months to finish restoring them all.

My “light touch” didn’t last long. By the time I went back to the ’39 era, I was no longer making minor changes here and there. I was overhauling each entire strip. The first major change was prompted by my frustration with the June 29, 1941 strip. Each of the color plates was badly shifted across the entire page:

And so, because absolutely everything was off-register, I found myself carefully blotting and smearing along every line of every shape in every figure in every panel, and I became increasingly exasperated at having to adjust so many tiny little spots and stripes. Restoring this strip seemed to be taking forever, and the result certainly wasn’t enough of an improvement to justify the effort. The final straw was the front of Alley’s jacket, where I found myself having to repeatedly make the exact same fiddly little correction to each buckle and every button. I’d had it! Something had to change! But what could I do? I knew by now that there was no automatic tool or procedure that would work, because none of the colors or textures were at all consistent… except the black lines themselves. I suddenly realized that, yes, the black lines are consistent! Why don’t I just mask them off, erase everything else, and then put the color back in with the Fill tool?

I tried this—and not only was it much easier and faster but I really liked the look of it:

Three strips later, I saw that this approach also had the bonus of homogenizing areas of color where the ink had faded unevenly:

In each instance I used the

newspaper scan to

match the original colors as closely as possible. From the June 29 strip

onward my process was

to blacken the blacks, white out the rest, and re-color the

strip.

A direct effect of this new approach, though, was that I was removing many halftone textures. I initially wasn’t sure whether this was a good idea. I had learned that some people insisted that halftoning was necessary for an “authentic” newspaper comic, and I worried that by making this change I might be inviting accusations of heresy. However, two factors helped make up my mind. Purple, brown, and gray had been a problem from the start; trying to blacken lines running through these colors automatically blackened all the abutting halftone dots, making the image ragged and bumpy. Hamlin’s shading lines looked like plucked grape stems! I had been grudgingly accepting this as an unavoidable problem until I encountered one panel, from October 5, 1941, which was entirely in purple:

No matter what settings I tried, every line came out jagged. The whole panel looked spattered and ugly. I finally realized that the only way to avoid this was to trace every line manually. But I couldn’t just grab a drawing pad and scribble at it; I am no V.T. Hamlin, and I feared the spectre of the Monkey Jesus. I used a mouse, and as I traced I kept my non-mousing fingers on the pixel-up/pixel-down shortcut keys so that every line’s width was exactly pixel-accurate to the scanned image. It took a much longer time, naturally, but when I saw the smooth new result I knew there was no going back. The halftone dots had to go. I was further encouraged in this decision when the University of Missouri sent me scans of their Sunday proof sheets—I was astounded to discover that Sunday proof sheets were all black and and white line art! The color choices had been made by the artists, but the halftoning textures required to produce those colors were not part of the artists’ work. Halftoning was an artifact of the newsprinting technology.

I can sympathize with folks who prefer to see halftones. Without halftoning, an old comic strip… doesn’t look like an old comic strip. And I appreciate how the halftoning can be seen as an integral part of the experience because it is a technological artifact of the medium. As an obvious parallel, there are those who will agree that listening to a vintage recording just doesn’t feel right, or seem authentic, unless it has the clicks, pops, and hiss of an old vinyl record. But I have to confess that I have no nostalgia for the newspaper medium itself. I want to see the art as clear as it can be—as close to Hamlin’s original as possible. I don’t want to see it run through a technological filter. For the same reason, I didn’t use any modern coloring techniques, either, with airbrushed highlights and shadows and gradients. That calls attention to itself; it too is an imposition on the original art. Hamlin’s original colorist used flat color (and the occasional gradient); and respect for the original artists’ work, in both line and hue, was my mantra. I don’t think I’m alone in this aesthetic. I recently read the delightful hardcover volumes of Peanuts Every Sunday, and have seen some reprinted Mickey Mouse Sundays, that eschewed halftoning in favor of “remastered” flat colors. So, even though I can understand that halftoning is, visually, what makes a comic a newspaper comic, I have become convinced that removing that noise, and making visible the thin and subtle detail of the linework, results in something much nearer to what the artists created.

It took me nine months, all told, to restore the 139 strips of Volume Three. Along the way Gary Sanderson provided me with the full-page strips that Rick had missed. I typically started with the last panel and worked my way backwards; when I worked start to finish, it always seemed exhausting to reach the final panel of the main strip and then still have three or four panels of “Odds n’ Ends” yet to go. Whenever I saw purple, brown, or grey anywhere, I groaned, because I knew that I was in for a lot of tracing. There were indeed certain panels (usually purple) where every single line had to be traced:

and some panels had specialized coloring that wasn’t just filling in the blacks. When I got to August 18, 1940, and I saw a purple panel that also had extra-thin lines and special coloring, I decided to time myself to see just how long it would take:

Because the bricks were entirely purple, those little hatching lines, and the outlines of the figures against the bricks, and of course the bricks themselves, all had to be traced (2 hours). The garments’ folds had to be traced because they were too thin to fill (1½ hours). Then I blackened the rest of the lines (½ hour). Then I put the colors back in, including the gowns’ opacity effects and the motion lines (1½ hours). That added up to five and a half hours for one panel, out of thirteen panels, out of a hundred thirty-nine strips.

While I was working on this project I had no shortage of suggestions from experienced touchup artists on what tools or filters I could try that might expedite the process, but all of those suggestions relied on at least some level of color consistency (across a panel) or some level of color difference (between the “black” lines and the halftone dots) and these old strips had neither. Any automatic process that successfully cleaned up one small area would inevitably ruin another. So I just kept plodding away. When I got back around again to May 18, 1941, where I had started, I thought I would be done—but my standards had changed so drastically that I had to do it again from scratch, along with the rest of 1941. It was fortunate that, as I again worked my way into late 1941, I found (why I was looking, I don’t remember) that the Austin Standard-Examiner had originally published their Sunday strips without color, and that these images were available in high-resolution grayscale on newspapers.com. Not all of their images had been digitized with good quality, and soft grayscale still had to be carefully restored into sharp black and white; but, for those weeks where I could use these grayscale strips, the lines were cleaner and more distinct than the color scans had been:

And, eventually, finally, I reached the end.

Toward the end I asked two people to provide front matter. I’m usually indifferent to editorial matter. I get a reprint book because of my interest in the strip, and the front matter is typically written by someone who was never directly involved in making it. In this case, however, Jonathan Lemon, the strip’s current artist and a long-time fan, was willing to provide a foreword, and the introduction was written by Pete Malik, who at age fifteen had paid a personal visit to Hamlin and Graue. Graue felt close enough to Pete, after that meeting, to make Pete a character in the strip (“Casey”, who visited the Island of Dinnys with Alley Oop and Toko in 1973), and Pete has vivid memories of his conversations with the artists. This book seemed a perfect opportunity to share with Hamlin’s fans some of Pete’s personal experience of the man. So these two pieces became the first pages.

Then, of course, the book needed a cover. I got John Cochran’s approval to use the art-deco frame design that they’d used for Volume One and Two, and, using a scan of Volume One, made sure that the lettering and design elements were the same sizes and proportions on the front and spine. For the cover’s central image, I kept trying different panels from various strips, but nothing seemed as energetic or exciting as I felt it should be. Then I remembered an unusual image I’d seen on eBay. After some searching I found it—an old fanzine, Yesterday’s Comics, had featured on the cover of its third issue a promotional drawing of Alley Oop, bursting out of a comics page, gleefully astride a speeding locomotive. I ordered the issue, scanned the image, colored it to resemble the 1930s “Orange Blossom Special” and placed it into the frame, where it fit beautifully.

I sent the book to the printer (Art Works Fine Art Publishing in Los Angeles) and waited to see the proof copy… and what they showed me was captivating. Astounding. Even better than I’d imagined! I could hardly wait to see it bound and finished… and, three months later, after it made its way through shipping and customs, I did. The book is now officially released and received. I’ve been gratified to hear from people who are delighted to finally have these strips in their hands and who enjoy the quality of the restoration. It was for everyone’s enjoyment that I did this, and it’s so rewarding to see it so well received.

It seems short shrift to now tell you so briefly how I came to create the other Sundays book currently slated for release, Complete Sundays 1982–1984. But the short version is this: Joseph Owens sent me scans of his early-80s collection, and I began restoring them mainly because, after those ’40s strips, they seemed to take no time at all. I had finished 1982 before I visited the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and discovered that they had Sunday proofs for those years; I was pleased to see that my restorations were as good (or even better!) than the proofs, so I hadn’t wasted my time, and I proceeded to color ’83 and ’84. I found that a three-row arrangement of the strips would make a Graue Sundays book the exact same dimensions as the Graue dailies book, so it seemed irresistible to create one. I contacted United Media to add one more book to our agreement, and they signed off on it, so I sent it to the printer. This final product also looks beautiful; it’s just waiting for its official release date.

So a big question: will there be more?

Until I visited the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library, my answer would have been a firm “no way.” I don’t have another nine pandemic-locked-in months to make a Volume Four. But now that I know the Museum has so many years of Sunday proofs—including 1942—the question is not whether there will be more Sundays books but how many there will be. On the production side, if I have mostly proof sheets and only have to restore some newspaper scans, that’s enough to make me keep working at it. I already have, and have colored, proof Sundays from 1955 and half of 1954:

On the release side, it depends one hundred percent on whether the books break even financially. I’m happy to say that it seems inevitable Volume Three will break even a few months from now, paving the way for Volume Four, which will be exactly the same format, size and price as Volume Three. The 1982–1984 book is a test case, because I don’t know what demand there is for Graue Sundays. If enough people order it, then I’ll proceed with 1985–1987 and 1988–1990, which are ready to go:

and then work back to other years. In short, because of the idiosyncracies of acquring and processing the source materials, the Sundays books may not come out in strict chronological order—but as long as people order them, I will continue to work to make the series live up to the name of Complete Sundays.

The Sundays books are available at http://www.aruffo.com/alleyoop; Sundays Volume Three can also be found on Amazon.

Anyway thank you so much for persevering ... and preservation!

Tuesday, February 21, 2023

Bringing Alley Oop to a New Generation, Part 2

Chris Aruffo is producing a new extensive series of Alley Oop reprint books, a labour of love project that has presented him with many challenges. I prevailed upon him to share some of his fascinating stories about the project with Stripper's Guide readers. This essay is the second of three.

If you are interested in reading the wonderful Alley Oop strips in high-quality but reasonably priced reprints, Aruffo's books are available directly from him, through your friendly neighbourhood bookstore or comic shop, Bud Plant, or Amazon.

The first slate of Alley Oop books was licensed and ready to go: six years of Graue from 1974 through 1979, and six years of Hamlin from 1933 through 1938.

But I knew something was missing. I knew the Bonnet–Brown strips were unaccounted for.

Prior to the strip’s official launch in 1933, one hundred twenty daily Alley Oop strips had been published by the small syndicate Bonnet–Brown. A document of Alley Oop’s first year would be incomplete without these 120 strips. But they are exceedingly rare. Bonnet–Brown was a tiny little syndicate; the original Alley Oop strip appeared only in a handful of papers, and we don’t know what most of those papers were. I was able to uncover the names of five papers that carried it: the Fairbault, MN Times; the Alva, OK Daily Record; the Waynesboro, VA News Virginian, the Washington, NC Daily News, and the McAllen, TX Daily Press. I hoped that this list might help me track down the strip.

But the problem wasn’t in finding the strip. The problem was finding it in a reprint-worthy quality. These strips had been reprinted once before, in 1997, by Alley Oop Magazine; heroically restoring the microfilm archive from Fairbault, and these images were already available for download from the Newspaper Comic Strips blog. If I were going to reprint the Bonnet–Brown run, it would have to be a substantial step up in quality. After all, thanks to Alley Oop Magazine anyone could see what the strips looked like, so the only point of reprinting them again would be to showcase Hamlin’s art.

And how could I possibly do that? What source could I possibly find with a high enough quality to see the artistry of it? Proof sheets and original art were, of course, out of the question. The syndicate and its clients were many decades gone and, according to the magazine, V.T. Hamlin himself had barely remembered creating these strips. The low quality of the two microfilm archives I was able to find online (Alva and McAllen) made it seem that the restorations in the magazine were as good as a digital source could get. The only way to get a better image, I supposed, would be from an actual printed newspaper… but what are the chances anyone saved these papers? I came across a news article suggesting that the Northwestern Oklahoma State University library, in Alva, might have paper copies of the Daily Record—but when I contacted that library I learned that, sure enough, they had long since digitized them and tossed the originals. Given the age and obscurity of the papers that carried Bonnet–Brown strips, and libraries’ ongoing need to clear out old, decaying materials, it seemed wildly improbable that any of these papers hadn’t been microfilmed and disposed of many years ago. And, without a better quality than microfilm to work from, the idea of reprinting the pre-NEA run was, for me, a non-starter.

Yet I couldn’t make myself give up completely on those Bonnet–Brown strips. I wasn’t optimistic that I’d unearth any new source in the few months I now had to produce the first book, but I gamely kept searching, thinking I might find some other papers that carried the BB strips, hoping that maybe, just maybe, I would find another paper whose microfilm archives were at least somewhat better quality so that I could potentially consider the possibility of reprinting them.

One of my desultory searches brought me to WorldCat. When I saw that the page was merely another mention of the McAllen Daily Press, I was about to close the window when a word in the listing suddenly arrested my attention: PAPER. Wait! What?! Paper?! As in actual paper newsprint newspaper? Not microfilm? I couldn’t be interpreting this correctly. Maybe WorldCat was simply recognizing that the Daily Press was, categorically, a newspaper. Even so, I contacted the institution named in the listing, the Briscoe Center at the University of Texas at Austin. I fully expected that they would tell me, as the university in Oklahoma had done, that they once had the paper copies but were now fully digital. But the librarian checked their collections and determined that yes, they had actual paper copies of the Daily Press. I still couldn’t quite believe it. But the Center’s policy allowed new inquiries to have a single sample scan, so I asked them if they could please send me an image of one of the Alley Oop strips. I was able to direct them to a specific edition and page because the McAllen paper is available on newspapers.com; for my sample I deliberately chose one of the strips that, in microfilm, had been murky and impenetrable. And when they sent me that sample image, my heart leapt into my throat, because this is what I saw (placed here next to a microfilm image for comparison):

Next was the matter of cost. A hundred twenty separate images, at the Briscoe Center’s usual scanning fees, seemed large enough to be prohibitive (that is, unrecoverable through book sales). I inquired and found that, as a “bulk” project, the Center’s administration offered a generous discount, but the amount was still large enough that I was uncertain. However, when I showed the sample scans to Rick Norwood he didn’t hesitate a moment. He instantly recognized that the historical importance of bringing these strips to light far outweighed the risk of financial loss and, as such, he immediately offered to sponsor the scanning. I accepted Rick’s offer, with the sole condition that restoring the strips would fall to me.

The librarians took great care to provide the best quality scans. They used an overhead scanner, rather than a flatbed, so some images were initially out of focus and had to be re-done. But they carefully laid weights on the pages so that each image would be flat and not suffer any distortion from the binding:

and they used good judgment in determining what scanner settings would most accurately capture the art. As each new batch came in I cooed and gushed over them, comparing them to the microfilm archives, exulting in the extraordinarily fine detail that we’d never been able to see in these strips before. We were disappointed to discover that the Briscoe Center was missing five editions of the Daily Press, but for these we were okay with using the microfilm images because, as they say, a hundred fifteen out of a hundred twenty ain’t bad.

There has been some confusion, I believe, about when the Bonnet–Brown run started and ended. Between the Alley Oop Magazine and the McAllen Daily Press we do have an answer. Alley Oop launched with an “announcement” strip, dated Monday, December 5, 1932 (reprinted in the Magazine):

The Daily Press did not print Monday’s announcement but started with Tuesday’s strip on December 6. The first six story strips are numbered, rather than dated, but the seventh strip is dated Tuesday, December 13, and appears on that date, exactly one week after the first, confirming that the strip was launched on Monday, December 5, and proceeded with six daily strips per week. At the end of the third week, though, something went wrong. The strip for the 23rd ran as scheduled, but the strip dated December 24 wasn’t printed until the 27th. From that point until the February 10th edition of the paper, the strip’s date was anywhere from three to five days behind the paper’s actual date. We can’t be certain whether the syndicate was failing to distribute the strips in a timely manner or if the newspapers didn’t bother to print them on the intended dates—but, in either case, after February 10th (strip date February 6th), the strips were no longer dated but numbered. It seems reasonable to suppose that the change from dates to numbers meant that, whatever the cause, V.T. Hamlin knew the strips were being persistently published on the wrong dates. The Daily Press continued its erratic scheduling throughout the run, randomly skipping one to four days in between strips and, on one occasion, printing two strips together. Fortunately, we can be certain that no strips are missing; the strips that are dated represent complete six-day weeks, and the subsequent numbering from 55–120 is uninterrupted. The final strip, numbered 120, was printed in the Daily Press edition of May 7, 1933. However, if the strip had been printed regularly, in six-day weeks without interruption, then the final strip would have appeared on April 13. That is to say: the newspaper’s erratic publishing schedule caused Alley Oop to appear in print as late as May 7, but, technically, the Bonnet–Brown strips should have run from December 5, 1932, through April 13, 1933.

Restoring the strips was tedious and meticulous, as it required mostly manual tracing and filling. My goal was to transform these images from their yellowed, faded condition into crisp, duotoned line art. It persisted in being a manual process. Photoshop experts kept recommending different time-saving tools to me, like Curves and Threshold and different kinds of filters, but none of these were helpful. For one, where the ink was faded, it was actually just gone:

With our human eyes we can easily infer from context when streaks are supposed to be white and which should be black, and we can clearly see lines’ smooth contours in the jagged residue of a newspaper texture. The graphics tools, however, can make no such distinction. There were no actual differences in color between where the ink had flaked off and the background; therefore, these qualitatively opposite spots were adjusted exactly the same by whatever tool I attempted to apply. In that strip which I’d requested as a sample, I ended up having to manually trace every one of the hundreds (thousands?) of tiny little white spots on the trees, in the grass, and on the dinosaurs, because I had found that any fill level that was light enough to correctly recognize the figures’ shapes and lines was not dark enough to blacken the backgrounds; when I tried to apply a fill, there were at least as many unwanted spots and speckles left over as the actual white spaces themselves, so it was just as much effort (and a better result) to just trace all the true white spaces and then wipe the rest to black. Fortunately, not every strip was badly faded, and on those strips I was pleased to use mostly fills rather than traces, but I still had to be careful because even those images were not consistent across their entire length. A fill setting that successfully restored one area would make a mess of another. And then, regardless of fading, very thin lines always had to be traced, because the paper texture guaranteed that they would be broken into pieces and therefore could not be filled. I have a drawing pad, but I only used that for small curved lines; for longer lines, I always used the mouse so I could be pixel-accurate to what was on the screen and not inadvertently transform Hamlin’s strokes into my own. Because Hamlin was so fond of drawing so many extremely thin lines for motion and shading, there were more than a few panels where I had to carefully trace every single line:

For each strip I saved the original scanned image and, during its restoration, I’d flip back and forth between the new and the original, making sure that the new one appeared visually identical. Then, finally, the McAllen paper also had the unfortunate characteristic of having cut off the sides of many strips, but, because there was rarely any significant detail at either end, I found that I could take the edges of the Magazine’s microfilm images and append them fairly seamlessly. The entire process was time-consuming, but ultimately not difficult. It was principally a matter of being careful and patient.

I found all the motivation I needed just by thinking to myself how wonderful it would be to share these with Alley Oop fans; after restoring each strip, I compared it to the microfilm image and marveled at what people would now be able to see. As tedious as it was to make sure that every line and every shape was accurately realized, I knew that none of us had ever had the chance before to see these lines as they truly were. I am pleased and proud to have been able to bring these strips to their proper light after all these years.

Monday, February 20, 2023

Bringing Alley Oop to a New Generation, Part 1

Chris Aruffo is producing a new extensive series of Alley Oop reprint books, a labour of love project that has presented him with many challenges. I prevailed upon him to share some of his fascinating stories about the project with Stripper's Guide readers. This essay is the first of three.

If you are interested in reading the wonderful Alley Oop strips in high-quality but reasonably priced reprints, Aruffo's books are available directly from him, through your friendly neighbourhood bookstore or comic shop, Bud Plant, or Amazon.

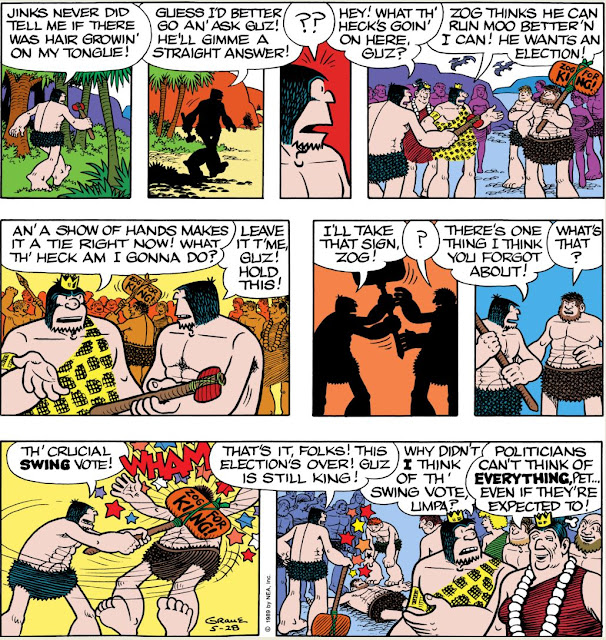

I’ve been an Alley Oop fan since I was eleven years old. I vividly remember encountering the strip in my local paper on October 22, 1983; there, among the banal levity of Priscilla’s Pop, Winthrop, and Short Ribs I found this panel of a fisherman… discovering a dead body?!

I was immediately hooked. Five years later, I spent the entire summer at the library, spooling through their microfilm archives to read every daily strip from 1937 to the present. Being able to read all the old stories was a marvelous experience; even so, I lamented that I was unable to copy and keep each strip as I read it.

I did clip and keep the newspaper strips from 1984 through 1989, when I left for college. United Media began offering their strips online in mid-1995; I downloaded the strip each day and, inspired by the new digital format, I scanned all of my clippings and sold them on a nascent eBay. I couldn’t have known, of course, that by creating files small enough to store on a floppy disk I was essentially destroying the strips’ artistic detail:

During the pandemic I saw the chance to repair some of these past sins. I created a newspapers.com account and got every Alley Oop strip from 1933 through late 1996. I sifted through every archive of every paper to be sure I was capturing the very best quality available. The challenge for Sundays was finding complete strips, because so many editors dropped panels to fit their pages. I typically found an incomplete strip in higher quality and then fit in lower-quality dropped panels from different sources. Having finished this project, I shared these strips with the Newspaper Comic Strips blog (and you can still find them there). And that, I thought, would be the end of it.

And then I happened across an eBay listing offering “proof sheets” of Alley Oop from 1975 through 1979. I didn’t know what proof sheets were, but I quickly found out; and, having learned that these would be of even better quality than the digitized images I’d been downloading, I immediately bought the eBay listing. Curiously, I soon received a message from the seller asking if I was genuinely buying these sheets. They informed me that proofs of unreprinted strips often sold to people who just wanted to read them, and who, having done so, came up with various excuses to return them for a full refund. I assured the seller that I really wanted to own the sheets. When I opened the package and saw the pages, I was astonished; these were, of course, the best possible quality short of the original art itself. And, as the purpose of proof sheets is to be reprinted, I began to wonder … would I be able to reprint Alley Oop, and finally have them on my bookshelf, as I have wanted all these years? I sent an e-mail to United Media and waited for what seemed a very long time.

The rights were available! And, to my great relief, they were affordable enough to make me believe that the project could break even. Having signed the contract for these five books, I needed to decide how many copies should be printed, so I wrote to Rick Norwood, who had, years ago, produced Alley Oop Book Four following the three Kitchen Sink reprints. Rick was excited to learn about this project and offered to support reprinting the first six years of the strip, which he’d been wanting to see in book form for a long time. I was delighted to accept his offer and so expand the project. I then wanted to make a total of twelve books, so as to fill out a year’s monthly scheduling, so I added 1974 to my own slate. Because I had by now donated my proof sheets to the V.T. Hamlin collection at the University of Missouri, they kindly provided in return images of the daily proofs they had which, by whatever cosmic coincidence, were from 1974; I was then able to round out what they didn’t have of that year with scans from The Menomonee Falls Guardian, which were printed in higher-than-usual resolution on some kind of magical newsprint paper that has never yellowed. The United Media licensing contract was amended and we were ready to go: six years of Graue from 1974 through 1979, and six years of Hamlin from 1933 through 1938.

And then I had to wonder: what next? Would this be the end of it? Adding the six Hamlin books to the licensing agreement had left the door open to reprinting even more, but I wouldn’t want to unless it could be done from proof sheets. Rick and I knew that, for the earliest years, restored newspaper clippings would be the best possible quality, and Rick had already begun feverishly restoring the early Hamlin strips from his personal collection. For later eras, though, it didn’t make sense to make books of restored clippings. If proof sheets for those years were eventually found, then the previously printed books would have been a waste.

But where on earth could proof sheets be found? Coming across that eBay listing was pure luck; now that I began actively looking for more I couldn’t find them anywhere. Heritage Auctions showed one listing that had ended years ago [That was my collection! -- Allan]. I found independent vendors with clippings and tearsheets but no proofs. It occurred to me to contact Jack and Carole Bender and, in a circuitous manner, I was able to get a message to them… in mid-winter, so I had to wait a few months before they were able to venture into their non-insulated attic to check. When they finally did, alas, there was nothing. Whatever had been there was now gone. There didn’t seem to be much hope.

There was one bright spot during this search, though. Responding to my question on the Facebook Alley Oop fan group, Germund Von Wowern volunteered that he had proof sheets for the latter half of 1938. Germund would have been happy to donate them to the project, but Rick insisted on buying them. They arrived in a gigantic box. In the 1970s, proof sheets were slightly larger than legal-size paper, with six daily strips on a page:

But these 1930s proof sheets were massive. Each sheet was a gigantic page of all the strips and features for a given day:

What Germund had sent me were two bound volumes with each enormous “book” containing three months of daily pages. Fortunately I was able to use my Avision tabloid-size book-edge scanner to capture them all, in four passes per page, without damage or warping. And this made Rick’s job easier, because he wouldn’t have to restore strips from that half of ’38. But no other replies were forthcoming. Nobody else stepped up to say they also had proofs. I started to believe that I’d just have to wait and hope.

But then Jonathan Lemon, the current Alley Oop artist, reminded me that the Billy Ireland Cartoon Museum existed. I remembered that I’d contacted the Museum at the very start of this process, but their reply had seemed unpromising—they’d sent me a spreadsheet of what Alley Oop strips they had, but I hadn’t been looking for newspaper clippings. I wanted proof sheets. So I had let that ball drop. Now that I was thinking again about the Museum, though, I looked back at that e-mail from half a year prior, and for the first time I read the title of the spreadsheet file. The title of the spreadsheet, you ask?

UNITED MEDIA PROOF INVENTORY.XLSX

I blinked—and then I blinked again. Had I been wearing Dorothy’s silver slippers all this time? This spreadsheet listed nearly every year of the strip’s existence, which is why I had assumed they had to be newsprint clippings. Was it possible that the Billy Ireland Cartoon Museum possessed proof sheets for all these years listed on the spreadsheet!?

Short answer: yes.

Our subsequent conversation confirmed that all of these holdings were indeed proof sheets and, furthermore, that the Museum would be willing and able to support this reprint project. Part of that arrangement was that, for such a massive project of thousands of pages, the only way to get it done in any timely manner would require me to come do the scanning myself, but it didn’t take me even a moment to agree to that condition (oh, go ahead, twist my arm)! We made the arrangements for my visit, I arrived to find all the requested boxes and folders ready to go, and for one week solid I just scanned scanned scanned scanned. I wasn’t able to get all the pages in one go—there were that many proof sheets, to begin with, yes, but, as soon as I looked in that very first box, I learned that the spreadsheet rows that had listed the same year twice weren’t indicating duplicate folders of daily proofs for those years. They were indicating folders of Sunday proofs. Between that discovery and the daily sheets I didn’t have time for, we arranged before I left that I should come back again one day to get the rest. And that “one day” has now arrived. It is looking more and more like we are, finally, going to see a complete run of Alley Oop reprints, from sources of the highest possible quality—thanks to special arrangement with (and the wonderful support of) the Billy Ireland Cartoon Museum.

You can find these books either at http://www.aruffo.com/alleyoop or on Amazon. All of the first twelve books from the ’30s and ’70s are already available. The next twelve are Graue’s ’80–85 and Hamlin’s ’54–’59, alternating each month through 2023. After that I expect to produce a couple oversize volumes of the wartime dailies, alongside all the regular volumes of all the other years, up through ’96, which is where the GoComics archive picks up. Complete Sundays v3 is also released, picking up where Dark Horse left off, and Complete Sundays 1982–1984 is completed and on the schedule (but how those Sundays books came about and how many more of those there’ll be is a story for another day). I don’t expect to be reprinting any of the books after the first printing of each is exhausted, but the inventory I have should last at least another couple of months, so you can still get 'em brand new!

Sunday, February 19, 2023

Wish You Were Here, from Walt Munson

I love Walt Munson's postcards, and he produced a ton of them. The colouring on these linen cards is just so vibrant and attractive, and Munson's gags are always great little chuckle-makers. He specialized in slightly naughty, or at least adult-oriented subjects, like this one on drinking.

The maker of this card is anonymous, but it is card number 60327, and the back states it as being from the "Drinkers Comics" series. Although undated, I'm guessing a publishing date in the late 1930s, or maybe it could be as late as the early 1950s.

Labels: Wish You Were Here