Saturday, April 30, 2016

Herriman Saturday

November 14 1908 -- Angelenos saw themselves as the ideal warm refuge for those stuck in Northern winters. Judging by the current population of L.A., I guess they were right.

Labels: Herriman's LA Examiner Cartoons

Friday, April 29, 2016

Walt McDougall's This is the Life: Chapter 14 Part 2

This is the Life!

by

Walt McDougall

Chapter Fourteen (Part 2) - It's a Long Lane that has No Turning

If anything out of the ordinary happens to the average dumb-bell, it's a miracle; if it happens twice to a scientist, it's a queer coincidence; if it happens thrice to a philosopher, it's a Law of Nature. Now, being dumb-bell, scientist and philosopher, I came to the conclusion that my experience of the newspaper game, as it is called, was about what happens to all of its players who are not crooks or rabbits, and I did as most of them do, tried something else.

I rented an office on Broad Street and established an advertising business under the cheeky title of "The Brain Shop," which very likely scared away as much business as it brought. Then there came to me a partner, whereby hangs a tragic tale. A well-known local politician, Clayton Erb, who had been Insurance Commissioner, a man of very wide acquaintance, offered to buy a half-interest in the Brain Shop, a proposition that was very acceptable inasmuch as it would relieve me of the outside work.

I thus became a sort of advertising counsel to several corporations, for one of which I produced a monthly colored comic paper of four pages [I believe McDougall is referring to the publication Giggles here -- Allan], several department stores and merchants, and in order to provide an outlet for my still exuberant energy, for I was only fifty years old, and still devoid of wisdom teeth, I started a little weekly called Sketches that sold about 2,400 every week right in the business section, handled by newsboys alone. I am now inclined to suspect that this would eventually have been my most profitable and pleasing means of support. Incidentally, I made a few cartoons for the Telegraph.

Late one Summer day Erb came into the office and said: "I will hand you a check for three thousand five hundred dollars in the morning. I am hurrying for my train now and can't stop. I am going to get a divorce from my wife and we will settle the matter tonight."

He lived out of town on a fair-sized estate called "Red Gables" from which the tragedy took its name. Next morning, as I entered the train at Pleasantville, somebody remarked: "That was awful about Clayton Erb, wasn't it?" I asked what he meant, and he handed me the morning paper. Erb had been killed by his wife as he rose from the dinner table. The trial attracted widespread attention, but Mrs. Erb was acquitted.

During this period I syndicated the "Log of the Ark by Japheth," which was widely accepted but holding strictly to the literal Biblical narrative it seemed incongruous to prolong it for a much greater period than the duration of Noah's maritime adventure, as any Fundamentalist will admit. When Roosevelt went on his hunting trip in Africa, I produced a series called "Teddy in Africa" that also widely syndicated, but it was not long before many newspapers hinted that some of their readers were indignant at my absurd or sarcastic depiction of their hero, and recognizing gradually that any form of caricature or criticism whatever of Roosevelt would be equally obnoxious, I began to ease up and finally ceased my efforts. This is what has always made the syndicating of political cartoons unprofitable; the protesting readers are always so much noisier than the others that the editors become alarmed at their din.

Next year a number of prominent Republicans induced me to start McDougall's Magazine, a publication designed to muckrake the muckraking magazines, for one thing, and, I presume, to rehabilitate the Republican Party in the estimation of the Best People. Hampton's Magazine, capitalized for millions, started that year, and spent, I heard, $60,000 a month, but it lasted only a few weeks longer than mine. I made the cover designs, cartoons, illustrations, wrote a serial entitled "The Golden Fleece," dealing with conditions in Atlantic City, where we sold ten thousand copies every month, made advertising cuts and everything except the poetry, in spite of which the periodical lasted ten months. It might have survived longer had I not been stricken by a severe attack of gout which laid me low, incapable of movement, for ten weeks or so. When I recovered, the damage was done. Many of those who signed up to take stock in the enterprise reneged and I was broke.

It was my first failure in health and in business, but I was still young. I have observed that the more senile of my old comrades are those who have clung like barnacles to one job, and that the ones who have been fired the oftenest are the most resilient, as if hustling for the meal-ticket keeps the glands in action.

I arrived in New York with eleven dollars in my pocket. Two friends who were awaiting me at the station took me out to dinner and afterward announced that we were booked for a poker game at the house of another old comrade, an opulent Wall Street broker. When I informed them of the state of my finances, they laughed the care-free laugh of those who live by their wits, and said my credit would be good.

I won $94 that night, and something assured me that old Father Knickerbocker's spirit was hovering over his prodigal son who had repented and returned to the old home town. In all my years in Philadelphia I had never won $94 in one night, nor in many nights. The next day I went to the office of the Globe and suggested a daily column entitled "Look Who's Here," in which the most notable of hotel arrivals should be pictured and written up in the style of the little country newspaper. Wright, the editor, enthused over the idea and agreed to pay me $100 weekly for the stuff.

I had singularly good fortune in having as subjects some notable arrivals, among them the Shah of Persia's brother (or brother-in-law—I've forgotten which), but, best of all, Sorolla, the foremost painter of the day, a genial, unassuming, stoutish and bearded genius who posed for me and in a long interview, his first in the country, gave me an opportunity of introducing him to the newspaper-reading public, which does not know a painter from a kalsominer.

He sold a half-million dollars' worth of pictures during one month, and I am convinced that it was all due to my boosting, but of course I may be in error.

At the end of the second week Mr. Wright told me that the owner of the Globe, a Wall Street man named Searles, had become alarmed over my contributions, thinking them largely fakes inasmuch as he could not credit me with a general acquaintance large enough nor the luck nor the ability to bag so many interesting subjects every week and he was afraid of libel suits! So the feature expired and nobody has ever had the nerve or industry to revive it.

I had already planned and now set to work to make six sample pages of a front-page comic, "Hank the Hermit," which on completion I submitted to the World, which was known to be in need of a new feature, but although "Hank" was approved by those in charge of the supplement, I now discovered that Mr. Ralph Pulitzer cherished a personal antipathy to me. His brother Joe told me that Ralph "did not like my style."

I formed a connection with the Western Newspaper Syndicate, managed by Charles Mar, who had been with the American, and in a short time "Hank" was booming, being used by many of the best papers of the country. Later, when it was earning perhaps $500 weekly, the World was again in distress owing to the desertion of their main attraction, George McManus, creator of "Bringing up Father," to the American. Pulitzer had another opportunity to avail himself of the feature, as my partners were very unsatisfactory to me, but I was to witness another instance of a business man allowing his personal feelings to influence him in a business deal.

While "Hank the Hermit" was getting into his stride, for these features take time to establish themselves, I issued, through the American Press Association, a tri-weekly feature called "The Outlet," a quarter-page package of cartoon, verse, wise-cracks and a strip, "Gink and Boob," which was acceptable to about a hundred papers and which certainly was work enough for two men at least. When "Hank" was placed under the management of the McClure Syndicate and his prosperity became assured, I dropped "The Outlet" and went to Florida to recuperate. Henceforth for years I spent eight or nine months in the year at Rockledge, Fla.

Two or three stories that I had written for my own ill-fated magazine I sold in New York, "The Criminal's Hat," which I am now attempting to dramatize, "Pikers Afloat," a novelette, and "The Last Contest," which the American Magazine published in 1912, illustrated by George Wright, and then in 1914 republished, illustrated by Ruyterdal, which was an extraordinary proceeding, for which Orville Wright wrote a commendation. For this tale I invented the launching and landing stage for airplanes on ships, which has been adopted, but as yet I have received no royalties for the invention. The story caused H. G. Wells in his "Predictions" to seriously assert that airplanes would not be used in warfare for fifty years!

Life now moved easily and uneventfully for several years, a big tuna, tarpon or devilfish being something to talk about for days, and a passing automobile with children wanting to see "Hank and his Animals," tourists from every State of the Union passing down the Lincoln Highway, becoming a pleasing interruption to the day's work. In the Spring of 1915, instigated by McClure's, now under the ownership of C. C. Brainard, who had once been a World reporter, I began a daily series, a strip, entitled "Absent-minded Abner," which was subscribed to by some seventy-five important papers, among them the Evening Sun, New York, which was very satisfactory, to me, at least.

It is generally supposed by the cartooning fraternity that each Presidential candidate selects his cartoonist just as he does his manager. As a matter of fact he does once in many years. Usually he does not know a cartoonist exists. The able publicity manager, of either party, takes care of the picking, not of one but many alleged cartoonists, who go on the payrolls of the party and help to swell the bills. In 1904 Davenport was chosen by Roosevelt, making one cartoon, "He Is Good Enough for Me!" among others, that doubtless affected many votes, but he had much difficulty in getting paid the money promised him.

In 1911 I began to flirt with Gov. Wilson and prepare his mind for a vigorous assertion of his rights to have a hand-picked artist, but I found very quickly that cartooning was a branch that he had totally neglected. He seemed quite unaware of the importance or the extent of this means of influencing public opinion, nor was he particularly disposed to learn anything about it. Several times that summer I went to Sea Girt, and also corresponded with the Governor, finding him apparently entirely disposed to place the matter of National Cartooning in my experienced hands.

About a month before the Baltimore Convention I endeavored to screw him down to a decision, having a sort of suspicion that having marooned Harvey, Inglis, Measday, Jim Smith and most of his original workers, he intended to have nothing to do with any of the men who had done so much for his political advancement. The following letter, written after the matter had been discussed often, shows how little real impression my arguments had upon what he called his "one-track mind," being, in fact, pure piffle, although I did not perceive it at the time.

State of New Jersey

Executive Department

May 7th 1912

My dear Mr. McDougall:

I need not tell you how sincerely I appreciate your letter of April twenty-fifth and must ask your indulgence for not having replied sooner.

I am a very barren fellow in ideas as to how I could avail myself of the services of a cartoonist. I am sure that your mind is more fertile than my own in such a matter. I am equally certain that there will be unrivaled opportunities in the approaching campaign for the use of wits.

I should esteem it a real pleasure to have a talk with you, as you suggest. I am expecting to be in my office here on Friday forenoon next and Monday forenoon next. I wonder if it would be possible for you to run down.

Sincerely yours,

Woodrow Wilson.

A few days later I went to Trenton, meeting the Governor on the trolley car and going to his office with him, where we talked for two hours. I found it quite impossible to get a definite statement from him, and it was long afterward that I learned that he hesitated mainly because I had been affiliated with a Republican paper for ten years or so and he was afraid I was politically unsound. Politics was so serious a matter to him, and he was actually at the time in such a nervous state, that even one or two jests of mine were taken up with intense gravity. One of these, that Bill Sulzer seemed to be really his most formidable adversary, actually seemed, incredible as it may appear, to perturb him visibly. In sooth, that day he was plainly depressed and quite lacking in his usual buoyancy. I left him, however, persuaded that everything was all right.

I went to the Baltimore Convention, luckily being able to rent a little house just within the police lines which came in handy for some of my friends. It was the usual sleepless, confusing, harrowing series of scraps. One day I met Harry Walker, Bryan's manager, who dropped a few words that electrified me. I had secured the promise of Champ Clark, Gov. Lowden and others to select me as cartoonist, but I had not considered William J. I immediately asked Walker where he was, and was told that he was in his room.

I found him talking with a man, a stranger, and, dismissing him, he took me into the bathroom, where he at once signified his willingness to use my services. He dropped a significant remark in doing so which led me to think that he had hopes of beating Woodrow. "I am only wondering," he said, "whether we can afford to pay your prices!" The next day he abandoned his opposition, however, and Wilson was nominated.

Not long afterward I discovered that Charley Macauley of the World had persuaded Wilson to accept his valuable services, but nothing was said to me about the matter. I did make an "animated" cartoon for the motion-picture branch of the publicity department under Robert Wooley, which took me two months to complete and was widely circulated.

One day I received a telephone message from Bob Davis, informing me that his boss, Frank Munsey, had just bought the Press and wanted to hire me as his cartoonist. He asked me to come down at once. I found Mr. Munsey in his office in the Flatiron Building, seated on a sort of dais, and he greeted me amiably, stating that he wanted me to make a daily cartoon for which he would pay the sum of one hundred dollars weekly. By this time a hundred dollars for a New York cartoonist was a mere trifle and comic-page men were getting four times that sum. I explained to him that much water had run under the bridge since I received a hundred dollars per week, but that I would make him a daily cartoon for that sum.

"I will want all of your time!" he said suddenly.

When I confided to him that I had two quite successful syndicate features in hand and could not, it was evident, drop them for the insignificant, even paltry sum of a hundred dollars, he snapped out: "Well, I'm taking chances on you! You've been identified with comic stuff for several years and your effectiveness as a cartoonist may be impaired." He was evidently quite piqued, and in spite of Bob's nervous signals to placate him, I retorted, very truthfully: "I'm the one who is taking chances. You have never made a success yet of any newspaper you ever tackled."

I cannot remember the details of the exceedingly animated and delightful conversation. I recall reminding him of the numerous occasions during the last five years when I had been arrested for libel in Philadelphia, but as we both lost our tempers the things we said were of no importance, but I enjoyed it more than anything that had happened to me in years. Bob Davis's distress and horror were simply delightful. My shocking lack of veneration for his boss agonized him. I never imagined Mr. Munsey was so human, and I think the old boy secretly enjoyed the experience, for I doubt if he ever had anybody stand up to him and talk back since he got on Easy Street. Finally, as I walked out, he uttered the last word: "I'll never have a cartoonist on a paper of mine!" He may have considered it a sort of promise, for as far as I am aware, he has never employed one. He fired Bill Rogers as soon as he bought the Herald, and no better man for that paper ever lived.

In nineteen-twenty-three I met him in the corridor of the Herald and he greeted me pleasantly. I said to him: "Mr. Munsey, it seems to me you need a good cartoonist pretty bad!" He smiled and replied: "You come and see me when newsprint gets cheaper." That he has, however, persisted in his silly obsession the following proves:

THE NEW YORK HERALD

280 Broadway

New York,

January 28,1924.

Walt McDougall,

Braemoor, Goshen, N.Y.

My dear McDougall: Mr. Munsey is still disinclined to put a cartoon in the Herald. He simply does not want cartoons in the Herald, and he owns the paper.

Very truly yours,

C. M. Lincoln.

One of the funny things about objections of offended owners who sternly refuse to use the work of men who have disgruntled them is that such men can sell anything that is valuable to their papers by simply using a nom de plume. I have had innumerable pictures printed under various names at one time and another merely to avoid subjecting Ralph Pulitzer, William Randolph Hearst or Frank Munsey to an attack of cardiac trouble. Many another man has had the same experience.

Labels: McDougall's This Is The Life

Thursday, April 28, 2016

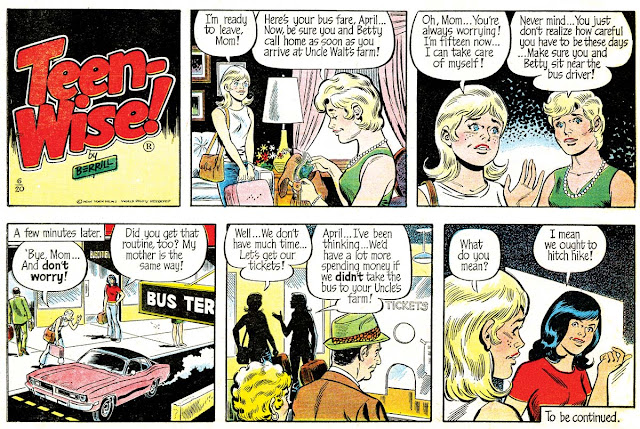

Obscurity of the Day: Teen-Wise

Certainly Jack Berrill had his heart in the right place when he dreamt up the comic strip Teen-Wise for the New York Daily News' Sunday comics section. His idea was to educate kids to the ways of the world, teach them moral lessons and good citizenship, and warn them away from dangers. But I have to say that the way it was done, by presenting readers with a never-ending cast of losers, most of whom never actually learn their lessons, was in my humble opinion really freaking depressing.

Just look at the samples above. In the top one we actually have an uplifting story, one with a great message and a good outcome. But in an otherwise good strip, Berrill has to have a loser invade the last panel and almost get the last word.

In the second strip it is abundantly clear that Bernie is embarking on a long horrible life of quiet sniveling desperation, and that his 'friends' are probably all going to end up as worthless trash; thieves and junkies probably. Could we not have ended with Bernie summoning up the resolve to ignore the advice of his loser friends? Is it realistic? Well, no. We all know some Bernies, and the one thing we can count on is that they'll never strike out on their own. But c'mon Jack Berrill, this is fiction -- you could give Bernie the break he'll never get in real life.

Then there's the third sample, a real classic. I don't have the next week's strip, thank goodness, but please Jack, please, cut these teenage pinheads some slack and don't leave them laying defiled and bleeding in a roadside ditch. Sure, that's what's likely to happen in real life, but please ...

Berrill tried to lighten things up with a mascot. Sorry, didn't work. The Teen-Wise Owl (seen in the top two samples), looked for all the world like a bug-eyed flattened piece of roadkill. It was like an angel of depression hovering over the proceedings, always around to taunt the weekly loser, but always sadly ignored.

Teen-Wise, the most effective depressant you can get without a prescription, seems to have begun appearing in the New York Sunday News sometime in 1966 (anyone seen it earlier?) and finally told the story of its last hapless loser on October 9 1977.

Labels: Obscurities

Comments:

National Lampoon in the early 70s ran a parody by Michael O'Donoghue, "Poon-Wise," which ended with a most temperamental Michael hammering the owl to death ("Goddamn stupid owl!!")!

guys are probably going to think I'm crazy, but I just bought 17 Teen Wise Sundays off ebay. Used to love this strip, and the era also reminds you of the Room 222 TV series.

I remember this strip. The damned owl would often swan in at the end and crow (see what I did there?), “‘Nuff said!”

To this day, whenever some geezer says that, I thinks of this odd strip.

To this day, whenever some geezer says that, I thinks of this odd strip.

Well, not for nothing, I was in the generation he was talking to and read it every Sunday during the '70's.

Unlike Room 222, or any of the crap on TV, Berrill wrote the truth, man. And it's because he didn't have a sniveling 'happy ending' a la Happy Days in the strip it had a huge impact.

As a snot nosed 15 year old I got a lot from those strips: you should have seen his 'Teen Parents' series.

Well written, great artwork, and he made his point. In what, six panels? Week in and out? Guy had more talent than the crappy TV shows you referred to.

Unlike Room 222, or any of the crap on TV, Berrill wrote the truth, man. And it's because he didn't have a sniveling 'happy ending' a la Happy Days in the strip it had a huge impact.

As a snot nosed 15 year old I got a lot from those strips: you should have seen his 'Teen Parents' series.

Well written, great artwork, and he made his point. In what, six panels? Week in and out? Guy had more talent than the crappy TV shows you referred to.

I loved this strip. It was fun and made you think. Too bad it wasn't continued. Let me know where I can get reprints.

Post a Comment

Wednesday, April 27, 2016

Obscurity of the Day: Texas History Movies

In 1926 news director E.B. Doran of the Dallas Morning News came up with an idea to tell the story of his state in comic strip form. What better way to get kids interested in the history of Texas than to tell its story in a lively, entertaining way with cartoons? He grabbed staff writer John Rosenfield Jr. to pen the strip, and artist Jack Patton, who was on staff at the Morning News' sister paper Dallas Journal, to draw.

The general concept was not completely new, but it was very young. J. Carroll Mansfield's popular Highlights of History pre-dates it by several years. However, Doran's baby is, as far as I know, the first educational history feature to limit itself to a specific subject like this. Strips and panels about state and local history would proliferate in the late-1920s and 1930s, but this appears to be the first of that particular breed. And not only is it a first, but it could arguably be called the best executed and certainly the most enthusiastically received of all that would follow. Rosenfield and Patton did a superb job of bringing history to life, enough that kids may have actually liked reading the strip, as hard as that may be to believe.

From the beginning, the strip's purpose of educating kids was pushed hard. The strip debuted on October 5 1926, shortly after the new school year had begun, and there is evidence that it was used as a teaching aid in Dallas classrooms right from the start. The Morning News also ran a contest in which kids could win cash prizes by answering questions about Texas history, questions that could easily be answered by kids who were clipping out the strips as they ran each day. The strip was so associated with schools that it even went on hiatus during the 1927 summer break.

Texas History Movies ran for a total of 428 daily episodes, ending its run at the conclusion of the 1927-28 school year on June 9 1928. The strip was so detailed in its coverage of Texas history that this large number of episodes only got it current up to 1885. According to the creators this was by design, "Here the cartoons end abruptly, not because there was nothing else worth telling, but because the things that happened after that make dull pictures; albeit, fascinating reading."

This, however, was by no means the end of Texas History Movies. In 1928 two different collections of the strip were published in book form. One was a complete reprinting by the P.L. Turner Company, the second an abbreviated version published by Magnolia Petroleum. The Magnolia version was printed in huge quantities and handed out free to school children, and was made part of Texas school curriculums. Eventually, in a large number of different printings over the span of decades, the publishing count reportedly went well into the millions. Even today, may Texas old-timers fondly recall the days when reading a comic book in class was not against the rules, at least in this one case.

Most of the information in this post comes from Weldon Adams, a comics researcher who works at Heritage Auctions in Dallas. I met him recently when I delivered a truckload of material to be auctioned there (more about that soon). You can read more about Texas History Movies, including a chronology of the reprint books, at Previews World. Adams also gave a talk about the strip, which is on youtube. Part 1:

and Part 2:

Labels: Obscurities

Comments:

Hi Allan,

I'm doing some assistant work for a documentary and we're seeking some help tracking down some 1920s comics in the style of Popeye or The Gumps that we can include in the film without having to pay a crazy amount for the rights. If you are able to help point us in the right direction at all given your expertise, that would be most appreciated; please email me at marcusdoherty92@gmail.com if so.

Kind regards

Marcus Doherty

www.marcusdoherty.net

I'm doing some assistant work for a documentary and we're seeking some help tracking down some 1920s comics in the style of Popeye or The Gumps that we can include in the film without having to pay a crazy amount for the rights. If you are able to help point us in the right direction at all given your expertise, that would be most appreciated; please email me at marcusdoherty92@gmail.com if so.

Kind regards

Marcus Doherty

www.marcusdoherty.net

Anything published in 1922 or before is in the public domain in the U.S. so it could be used. But this would not necessarily (and probably not) apply to later reprints of those strips.

Thank you for posting this. I’m working on a research project about my uncle, underground cartoonist and proud Texan Gilbert Shelton who went on to create wonder wart hog, the fabulous furry freak brothers, and other titles beginning in the late 1960s. In my research, I discovered that he was influenced as a kid by Texas history movies. It’s also interesting that his fellow underground colleague, Jack Jackson with later re-illustrate Texas history movies.

Post a Comment

Tuesday, April 26, 2016

Ink-Slinger Profiles by Alex Jay: J.C. Argens

The 1900 U.S. Federal Census recorded Argens, his parents, Henry and Arzelie, and his older sister Fannie, in Reno, Nevada at 307 Virginia. Argens’s father was an iron molder.

In the 1910 census, Argens and his parents resided in Beckworth, California on Portola. The family later moved to San Francisco.

Argens was a medalist and graduate of the John Swett grammar school as reported in the San Francisco Call, December 21, 1912.

The 1917 Crocker-Langley San Francisco Directory had this erroneous listing: “Argens Henry (Arzelie) cartoonist h 2297 Sutter”.

Argens signed his World War I draft card on June 5, 1918. He was a San Francisco resident at 283 Church Street and his occupation was newspaper artist at the Bulletin. Argens was described as medium height, slender build with gray eyes and brown hair. Information regarding his art training has not been found.

In 1918 Argens contributed to Cartoons Magazine in its January issue; in March here, here and here; and May.

The Fourth Estate, September 14, 1918, reported Argens’s new job.

J. E. Murphy, formerly of the San Francisco Evening Call-Post, and now on the New York Journal, was succeeded on the Post by John C. Argens, former sports cartoonist on the San Francisco Bulletin.The Sante Fe Magazine, April 1919, reprinted Argens’s Seeing San Francisco from Cartoons Magazine.

In 1920, cartoonist Argens and his stenographer wife, Ruth, lived at 790 California Street in San Francisco. San Francisco city directories from 1921 to 1926 listed Argens as a San Francisco Call cartoonist residing on Jones Street. The 1927 directory said Argens was a San Francisco Daily News cartoonist who resided in Burlingame.

American Newspaper Comics (2012) said Argens produced Amundsen’s Life for the Daily News from March 22 to April 9, 1927. Agrens’s cartoons appeared in the Sausalito News, April 7, 1928, and Madera Daily Tribune, April 10, 1929.

Argens home address was 1907 8th Avenue, San Francisco, in the 1930 census. The newspaper cartoonist had two sons, Henry and Jack.

According to the 1937 directory, Argens was Chronicle cartoonist. The following year Argens was at 3536 Kerckhoff Avenue in Fresno, California, where he cartooned for the Bee.

Fresno Bee 12/12/1937

The Bee, July 7, 1945, reported Argens’s injury in San Francisco.

John Argens, 48, a San Francisco newspaper artist who formerly was a staff artist for the Fresno Bee, was seriously injured yesterday when he was hurled to the floor of a cable car in the bay city when the car’s grip locked on a cable. Argens suffered head injuries and was transferred to the St. Luke’s Hospital...Argens passed away January 20, 1962, in San Francisco, according to the California Death Index. The 1962 directory had his address as 1390 Filbert Street.

—Alex Jay

Labels: Ink-Slinger Profiles

Comments:

My special thanks to you and the blog. Due to the material that was posted on E. B. Sullivan "Sullie." A couple that had some of his art work contacted my sister and they sent us original art work, newspaper clippings etc. I am still sorting through the stuff but among the things is a letter from the Chicago Tribune that they were going to have to cancel the Bucks McKale strip and several other strips due to war time paper shortages. Bucks did run into the middle of September of 1943 in the Boston Post. During the war Sullie was editor of a newsletter for Patterson AFB (now Wright-Patterson). He drew cartoons for the newsletter geared to different groups on the base such as "Private Stuff" "Guard Gags" and others. Thanks again for providing the way to find out more about my relative. Carolyn Yancey Kent carolke5@aol.com

Post a Comment

Monday, April 25, 2016

Obscurity of the Day: John West

Before World War II, it seemed like every new strip put out by the Chicago Tribune-New York News Syndicate was touched with gold. After the war, it was a much different story. The syndicate seemed to be completely clueless, and brought out a long succession of stinkers. The Sunday-only strip John West, which debuted on April 7 1946, was certainly one of them. I'd definitely lose a decent size wager if the strip ever appeared outside of a Tribune-owned paper.

Not that John West was a total loser. John J. Olson was an extremely talented artist, whose evolving style over the life of this strip just got more and more impressive. It was the storytelling that seemed to mystify Olson, who tried to do way too much in each strip. Given that he had a mere third-page per week in which to work, his penchant for cutting from one scene to another two, three or even more times in the space of a single strip was enough to give readers a case of whiplash. Olson also had trouble figuring out what he wanted the strip to be about (or too many directives from behind the scene). The strip started out as sort of a jauntily adventuresome hillbilly strip, but then our hero all of a sudden grew up, got involved in hardboiled plots, and eventually ended up concentrating on, of all things, deep-sea diving.

Olson obviously knew his strength was in his drawing. Before the war, he was reportedly an art assistant for Ed Moore and Norman Marsh, and after John West rode into the sunset on November 6 1949, he got a very long-term gig as Dale Messick's art assistant/almost ghost on Brenda Starr.

Comments:

In the Art Wood Collection, there is a John West Sunday by Olson that is dated 7-23-50. There are blue pencil editorial marks, but no copyright paste-on.

Sara W. Duke

Curator, Popular & Applied Graphic Art

Prints & Photographs Division

Library of Congress

Washington, DC 20540-4730

sduk@loc.gov

Sara W. Duke

Curator, Popular & Applied Graphic Art

Prints & Photographs Division

Library of Congress

Washington, DC 20540-4730

sduk@loc.gov

Wow! Even if that strip never made it into print, it's so much later than my end date (from the Trib) that they must have had someone else running it longer. Well, all we can do is keeping looking.

Thanks, Allan

Post a Comment

Thanks, Allan