Thursday, December 14, 2017

King News by Moses Koenigsberg: Chapter 14 Part 2

King News by Moses Koenigsberg

Published by F.A. Stokes Company, 1941Chapter 14

The Magic Back of "The Funnies" (part 2)

link to previous installment link to next installment[I'll be offering some footnotes for the material in this chapter. They are numbered in red, and the footnotes will be found at the end of the post. -- Allan]

Newspaper Feature Service lost none of its militance in the rout of the Buster Brown League. Two other promotion plans were pressed forcefully. Both were missionary campaigns. They were designed to tinge and, if possible, to modify the tastes of newspaper readers. Following a logical course, each would ultimately advance the sales of our budget by sharpening the public demand for dailies in which the features appeared. First, it was necessary to assure this appearance. That entailed displacement of items under current commitment. Such changes usually meant added cost to the publication. There was the chief obstacle.

The average publisher measured a syndicate offering with an expense yardstick. He was unprepared, if not unfitted, to estimate its value as a productive unit. Unless it was a feature of commonly recognized merit, it fell into his classification of miscellany. This set up one of my favorite targets. Batteries of statistics, reasoning and ridicule hammered at the term “miscellany.” Its inclusion in the inventory of a metropolitan daily was denounced as a disgrace. It was merely a polite name for filler—“the dregs of journalistic torpor”—the type kept standing to “plug holes” in page forms. No other shortcoming of the publishing craft was more widespread. It hung over from the days when the collection of news was as arduous a labor as its selection had since become.

Broadsides and brochures expounded the theory that the filler not only cheated the reader, but also disparaged the worth of adjacent linage. Here is a condensed extract from one of the pamphlets with which newspaper offices were besieged:

“Filler” is a good word, but it represents a bad idea. If a man ate sawdust to fill his stomach, there would be no quarrel with the sawdust. The quarrel would be with the man. The reason “filler” represents a bad idea is because it is THE SAWDUST OF THE NEWSPAPER MEAL. . . .

A simple filler, worst when it is long, but bad whatever its length, is not merely wasteful, not merely an obnoxious preemption of good selling room; it is an affront to every principle implicit in the very name “newspaper.” “Shorts?” Yes—shorts that are as good in quality as the long stories; shorts that bear the same relation to the newspaper repast that any edible does to a proper meal. ... So, here’s a pledge not even to use the word “filler” in a newspaper office. Let us substitute “short” and maybe the better thing will a little sooner follow the better way.

The anti-filler campaign boldly aimed at inflation. Higher appraisal of a newspaper’s compass would prompt closer scrutiny of its prospective contents. And, with a confidence that in any other circumstances would have been too presumptuous for tolerance, Newspaper Feature Service foresaw in the new order a decisive advantage over its competitors. This was not an empty conceit. It was backed by the performance of a tutelary role safe from assumption by any rival organization. No other feature-making bureau at that time could have cited as authority for similar pretensions a managerial record covering all departments of metropolitan dailies. And there was no one with the “audacity or effrontery” to share my right of way on a path of “patronizing, meddlesome intrusiveness.”

Abstention from such “meddling” by other syndicates left Newspaper Feature Service an open field for the promulgation of its major thesis—habit-forming, the core of newspaper supremacy. In the structure of this theme abide the relationships that bind seekers of current intelligence to the printed word. It houses the principles, the formula, the methods and the secrets of circulation growth. It is the domicile of reader interest. A different latch hangs at every entrance, but one master key is held by the mightiest force extant—habit.

The vitality of the newspaper being bound up in the mental habits of the reader, Newspaper Feature Service frankly addressed itself to multiplying and intensifying those addictions. An effective instrumentality lay at hand. It was a day-to-day suspense achieved with serial treatment. The device held little novelty. It had reached my attention first in several weeklies that prospered greatly during my boyhood, among them The Fireside Companion. The technique was obviously simple. Each story installment concluded with a breathtaking crisis. It was a trial to wait for the next issue to learn whether the hero saved the heroine or whether the villain hurled her from the brink of the precipice to which she had been hanging by her golden tresses.

Similar effects, sharply modified, of course, were sought with various units of the budget of Newspaper Feature Service. On the Chicago American, ten years earlier, it had been my practice to handle outstanding news along parallel lines. When the facts lent themselves to the purpose, the principals were put through the paces of a real-life drama.

Faithful adherence to the actualities precluded any idealization, but the different characters were projected into the intimacy of a painstaking novelist’s portrayal. Their early environments, their friendships, their hopes, their fears, their indulgences, their sacrifices, their admissions of fault and their claims of virtue were spun into the texture of the main narrative. Lively reader interest was maintained in some cases for weeks or months at a time. When a lag of events retarded the flow of action, the pitch of the yarn was sustained by prodding the curiosity that had been excited concerning the dramatis personae. Mystery—whether it curtained a crime, a romance or a tragedy—yielded the richest opportunities to sow the seeds and reap the harvests of this continuity of attention.

A wide-awake editor of that day, unlike many of his successors, did not flinch from the accusation that he fostered criminality by dissecting it. He brushed aside the mawkish charge that notoriety, no matter how baleful, dangled an aureole over a felon’s head. He respected his readers. He didn’t believe his circulation embodied a formidable section of dormant outlawry that awaited only the recounting of banditry to be roused into imitation. He did believe that a challenge to society, by any grave violation of law and order, should be laid bare in its full significance. Its implications must be explored with the thoroughness of a surgeon probing an ulcerous tissue. The journalist and the physician rendered cognate services. Each performed a sanitary function. But the newspaper operation was merely a phase of a highly specialized skill—“the knack of developing a story.” It had no master who excelled my mentor, Foster Coates. It fell into disuse under the manifold pressures of news readjustments attending and following the first World War. It has become a lost art.

It may be said of this type of ingenuity that it died a double death. For several years it had found duplex expression. Its exploitation in words was accompanied by presentation in pictures. The writer and the photographer vied in sequential dramatization of the same news on the same pages. An instance of this method was given in an earlier chapter describing the capture in 1903 of Gustave Marx, one of the infamous Car Barn Bandits. A growing sensitiveness to criticism gradually nudged this sort of pictorial objectiveness out of the daily press.

Publishers shied from a bogey of sensationalism. Many bowed to the condemnation of those who charged that telling a yarn in action photographs exemplified yellow journalism at its worst. They relinquished this mode of reportorial vividness only to witness its creation of enormous circulations in subsequent years by such weeklies as Life, Look, Pic and Click. Some of the journalistic nabobs who had shunned the field found solace in a sense of virtuous forbearance. Their feeling received affirmation from those magazines that indulged excessive “candor of the lens.” These covered a multitude of sins in uncovering a multitude of skins.

It was the boast of Newspaper Feature Service that its budget provided a full complement of daily and Sunday features for metropolitan publications—’“everything except local and telegraphic news and the backbone of character which the editorial page must supply.” Magazine and colored comic sections composed the bulk of the Sunday schedule. For each week day, the releases included two pages devoted in the main to women’s interests, four humorous strips and cartoons, and gossip for the sports department. This was amplified with a variable catalogue of signed articles on popular topics. Since a syndicate serves clients of all shades of political bias, these contributions were prepared in scrupulous avoidance of controversial repercussions.

The serial quality was injected into every feature susceptible to the ministration. Where episodic dosage was impossible, tonics of self-interest were concocted to titillate reader expectancy. A daily essay on health, by Dr. L. K. Hirshberg, was a prime example. He interspersed medical lore with fascinating theories as provocative in the boudoir as in the gymnasium. One treatise discussed “Why Your Eyes Are Brown and What Brown Eyes Mean.” “What Happens When You Blush” and analogous subjects permitted Doctor Hirshberg to beguile his readers with introspective games. It was less difficult to devise the titles for his articles than it had been to find the physician willing and able to write the texts. The science of medicine has never been overly cordial to journalistic adventure.

If ownership were obtainable through priority of practice, it would have been possible for me to vest Newspaper Feature Service with the exclusive right to serialize comics. I introduced the process in the Chicago American with A. Piker Clerk. Clare A. Briggs drew that feature under my direction in 1904. It was the first serial comic strip published in an American daily.1 It was the prototype of A. Mutt, which appeared three years later from the pen of H. C. (“Bud”) Fisher and which developed into the preeminently successful Mutt and ]eff.

It would be a dereliction for me to leave the life of A. Piker Clerk to chroniclers less familiar with his sterling service as a pioneer. The history of the art demands a more accurate, if not a more sympathetic, account of his inspiring career than others have vouchsafed. Gilbert Seldes, in his sprightly work, The Seven Lively Arts, placed Piker’s habitat in the Chicago Tribune. More grievous was the cavalier affront inflicted by William Murrell in A History of American Graphic Humor. It is accentuated by the laborious research incorporated in that tome. Murrell credited Bud Fisher with “the first comic strip to be printed daily.” That would deny to A. Piker Clerk not only his patriarchal status, but also his ancestral relationship to Fisher’s A. Mutt.

The atmosphere of bubbling spirits and carefree exhilaration, commonly associated with the generation of popular humor, was missing from the birth of the first serial daily comic. The labor pains were pitiable. The accouchement of A. Piker Clerk might be bracketed in some respects with the parturition of Pantagruel. The Rabelaisian progeny attained a greater longevity but occasioned fewer childbed worries. The conception of Piker was the climax of a toilsome struggle with reader capriciousness. Incidentally, it instanced the exhaustive and protracted drudgery sometimes required to dig a single well of newspaper entertainment.

A nip and tuck contest between the Chicago American and the Chicago Daily News for circulation leadership had reached a peak in 1904. Max Annenberg managed the American’s distribution. Together we studied the fluctuations shown in every district report. Printing schedules were revised. The fleet of trucks was reorganized. Zones of delivery were shifted. Despite all the maneuvers we executed, the Daily News held its lead. The weakness of the American’s position lay in the fickleness of buyers of the edition called “Final Sports.” The ultimateness indicated by that title was, in the chaste language of Max Annenberg, “a come-on.” The press run began at 3:30 p.m. Its finality was repeatedly canceled with replates containing fresh news. The order in which these appeared was marked by stars alongside the “ear” or label. Usually, four such asterisks identified the very last or honest-to-goodness “Final Sports.”

The sales record of this quadruple issue seesawed between a maximum of 110,000 and a low of 60,000. If these figures could be pegged midway—at an average of 85,000—the American’s daily total would reach 315,000. That would exceed the Daily News’s latest statement by more than 10,000. The problem was up to me. Its solution lay, not in external manipulation, but inside the columns of the newspaper. The “Final Sports” files for several months were thoroughly searched. Every element was subjected to microscopic analysis. All pertinent data were collated— weather conditions, the rise and fall of public concern in general affairs as reflected by headlines and cash collections from news dealers, large out-of-town excursions and other mass distractions. This information was checked against the calendars of sporting events. The intensive survey compelled one conclusion. The inconstancy of the final edition readers was confined to those who bought it for its sports pages.

Clearly, something beyond the ordinary flow of news or the specialties already offered them was necessary to convert the desultory custom of these buyers into a steady demand. It should implant in them every day a piquant curiosity that could be satisfied only in tomorrow’s American. In retrospect it would seem that a wearisome postgraduate inquisition dug up a conclusion that should have been manifest to a primary-grade student. But so did Columbus with his egg trick. Moreover, that was some years before Newspaper Feature Service launched its campaign for recognition of habit-forming as the central pillar in the building of a newspaper.

The value of a journalistic idea is set by its integration. Incorporeal, it may be more of a nuisance than an asset. So, the decision to bolster the “Final Sports” with a feature holding day-today suspense was merely the beginning of the job. First, a satisfactory vehicle must be found. It should be a pastime with the widest following and the fewest interruptions. Prize-fighting was illegal in many states. Basketball was yet in the adolescence of its popularity. Baseball, football, tennis, golf and other sports with seasonal intermissions were excluded. My choice rested on the chief sport with all-the-year-round activity—racing.

With the turf as the background for a serial, it was important to find an elastic medium of narration. Neither romance nor serious adventure was suitable. Linked to the paddock or the track, either would be narrowed to a pattern of limited appeal. Not by preference, but by a methodical procedure of weeding out less logical possibilities, pictorial humor was chosen for the storytelling channel.

No severe strain of imagination was required to visualize a small-time blow-hard with abundant eagerness but deficient wherewithal to back the horses. The average reader would surely notice in the type some familiar quirk or facet. Thereafter, it would be only customary to keep a watchful eye on the fortunes of this amusing busybody. Each day, the ludicrous predicaments through which he floundered to obtain betting funds would whet interest in tomorrow’s outcome, especially the results of his wagers. Thus was evolved the theory of the first serial comic. Its success would depend on the skill with which it was translated into a daily strip with pen and ink.

|

| Clare Briggs |

The next step was to prove that the series could be maintained consecutively with day-to-day suspense. Eighteen connected episodes— three weeks’ releases—were blocked out. The drawings were turned over to Ernest L. Pratt, head of the copy desk. He was to invite suggestions for a main title from the seven sub-editors or copy readers under his direction. Pratt, himself, offered the name that I adopted. Such was the inception of A. Piker Clerk, the first serial comic, which happened also to be the first newspaper strip printed daily in full-page width 2. The whimsicality of its fate was in sharp contrast with its laborious origin.

A. Piker Clerk scored an instantaneous hit. It was reflected in the Chicago American's circulation reports. Briggs shared my gratification. We had scarcely quit swapping back-slaps when Foster Coates, my sponsor in the Hearst organization, dropped into Chicago on an unheralded visit. Coates’s trips of inspection were seldom without a particular purpose. On this call, he disclosed no special errand. My angling for a comment on our latest feature elicited only a perfunctory response. This unusual reticence was puzzling. The mystery cleared as Coates was telling me goodbye. “That’s a great idea you’ve given Briggs to handle,” he said with strained casualness, “but Mr. Hearst has some doubt about it. I’m afraid he thinks it’s vulgar.” 3 That was the anathema maranatha of the Hearst establishment. No offense inside its precincts was more damnable than vulgarity in print. This recollection, tracing a tangent with the journalistic, social and political currents of that period, attaches to A. Piker Clerk a tag of historic symbolism. It frames a pungent paradox.

It is doubtful whether all the other publishers in America incurred as much violent criticism as was directed against Hearst personally. A great part of this censure was based on the assumption that his publications were unforgivably meretricious—that their contents teemed with lascivious suggestion. Yet not a dozen newspapers in the country were edited with more meticulous regard for decency than the Hearst press.

My concept of the regimen was partly expressed in this instruction: “Never use a term or a phrase that might prompt a thirteen year-old girl to ask such a question as you would find it embarrassing to answer to a neighbor’s child.” This was carried to the verge of prudishness. The baneful words “rape,” “abortion” and “seduction” were strictly banned. Under prohibition also were clichés like “criminal assault,” “betrayal under promise of marriage” and “born out of wedlock.” In the atmosphere of these taboos, Foster Coates’s message from Hearst sounded the death knell of what at the time was the dearest offspring of my brain.

Despite his inglorious and untimely end, the progress of the comic art was punctuated with various observances of the memory of A. Piker Clerk. Once, he was apostrophized in a copyright suit. A tribute of exquisite irony was jointly presented more than a decade after his demise by three Hearst newspapers in New York. They published simultaneously during several years three different strips, all in zealous, though unflattering, simulation of A. Piker Clerk. 4

Briggs had delineated a ridiculously busy betting fan. His New York imitators presented sordid race-track habitués rejoicing in caddishness. One series, Ken Kling’s Joe & Asbestos, outpikered Piker. It turned into a touting agency. Evidently, Hearst’s sensitiveness to this sort of vulgarity had undergone marked abatement. The transition was not explained by the ancient adage, “Times are changed and we are changed in them.” Privately, Hearst was no less the aesthete than ever. Professionally, he had taken on a full partnership with opportunism.

The conventional furniture of the humorous strip in 1913 was built out of the “gag” and the “wise-crack.” The chief purpose of the usual set of paneled scenes was to point a joke. The funnier the characters, the bigger the laughs they would command for the artists’ witticisms. These popular figures constituted assets to be jealously guarded. Their value had been proved as puppets on strings tied to fixed staples of entertainment. Most of their creators were dubious about tangling those strings in skeins of unfinished yarns. Comics that had fared well on gags and wisecracks with daily finales might not thrive on a diet of unclosed incidents with a continued story dressing.

Tom E. Powers, the noted caricaturist, cast a quaint light on this state of uncertainty. Powers enjoyed relaxation from his powerful cartoons in the frequent but irregular drawing of Mrs. Trouble and Joys and Glooms. He turned down a proposition to pilot Mrs. Trouble through a six-days-a-week routine. His refusal was based on my requirement for “overlapping the next day.”

“That is a slave-driving editorial trick to double the art work,” he declared. “You expect to make two laughs grow where only one grew before. It used to be enough just to leave ’em laughing. Now, you want us to kiss them coming and going with the same smack. You won’t get away with it unless you hire novelists or playwrights to wet-nurse the artists. And at my time of life, I couldn’t think of wearing diapers.”

Cliff Sterrett and Duke Wellington were among the large contingent of newspaper fun-makers who did not share Powers’ view. Sterrett, with his Polly and Her Pals, and Wellington, with That Son-in-law of Pa’s, enlisted in the Newspaper Feature Service phalanx of serialization. Twenty-eight years later both series were still among the popular favorites, though neither had maintained unbroken adherence to the “carry-over” style of plot construction.

An outstanding classic of syndication evolved from a preparation equally assiduous as the hectic approach to A. Piker Clerk. There was no buoyancy of competitive effort or any lift of lively imagination in its genesis. It was the goal of my search for a continuing element of compelling interest to the greatest single class of desirable readers—the family circle. The extravagance of its preliminary title—Revelations of a Wife—was at sharp odds with the mathematical care that guided its planning. It stretched into the longest story ever told in print.

Turning the twenty-seventh year of its serial life in 1941, this unending yarn, having been again and again renamed, had run to approximately 8,509,000 words. That exceeded by more than nine times the length of Shakespeare’s works. Its statistics are no more striking than its anecdotal color. It was the pivot around which swung many a newspaper skirmish. It clinched the sale of a daily and added $100,000 to the selling price. That transaction furnished an index to the '‘pull” exerted by this extraordinary feature. It is worth recital.

J. David Stern, the human dynamo who afterward operated concurrently the New York Evening Post, the Camden Courier and Post, and the Philadelphia Record, was publishing the News-Record in Springfield, Ill. He had moved to Illinois from New Brunswick, N. J., four years before. He enrolled as one of the early clients of Newspaper Feature Service. Thomas Rees, publisher of the well-entrenched and prosperous Illinois State Register, had not allowed the newcomer to make him alter the even tenor of his ways. He traveled extensively. It was on his return from a pleasure trip late in 1918 that Rees was shocked out of his feeling of security. He learned that the News-Record was claiming more local subscribers than the Illinois State Register could boast and that its claim was probably correct.

Rees canvassed the situation in thorough alarm. His circulation manager reported that the chief factor in the News-Record’s growth was a serial story of family life—Revelations of a Wife. Rees was incredulous. That sort of thing hadn’t happened in Springfield before. But the farther Rees’s inquiry progressed, the more his incredulity receded. At last he decided on a heroic measure. If this to-be-continued-tomorrow tale had such potency, he would take it away from the News-Record. He would outbid Stern. The Illinois State Register’s offers to Newspaper Feature Service finally reached a figure seven times greater than the amount Stern paid.

Strenuous pressure was put upon me by both Rees and Stern. The tempting increase of revenue tendered by one was met by the other’s assertion of a moral right. Rees was not merely negotiating for a feature. He was striving to acquire—so far as it was transferable—a vogue that had been implanted and cultivated in the community. The seeds had been supplied by the syndicate. But the crop stood on the soil of the News-Record. Even before Rees’s proposition to Newspaper Feature Service had been declined, word reached me confidentially that he was dealing direct with Stern. In May, 1919, he consummated what in that time and section was a highly sensational newspaper coup. For the purposes of the transaction, he and his partner, Henry Clendenin, associated themselves with Lewis H. Miner, owner of the Springfield Journal. The News-Record was bought and put out of existence. Rees complained that $100,000 of the price exacted was chargeable to my refusal to close a contract with him for Revelations of a Wife. “That represents what Stern collected for what you should have delivered to me,” he explained.

Few undertakings with literary flavor ever set out along more methodical lines than marked this feature. First, the plane of reading interest was plotted. It touched at every angle the housewife in modest financial circumstances. The next task was to find the greatest common divisor in each department of her outlook. It is amusing to recall the ponderosity of this research, especially in the light of its result. It had been an arduous quest for a flagrant fact. A sea of psychology had been explored to discover its surface. The lady in question was wholly perspicuous. Household events dominated her life. Their importance to her ranked in the order of their nearness. Only second to her own were the domestic affairs of those close at hand. She would be held in rapt absorption by the daily diary of the woman next door.

The range of sympathy open to the compulsion of such a record of intimacy would be fixed largely by the number of social averages that it comprehended. The diarist’s middle class must be jealously preserved. She must not be a pampered pet. Nor should she be a soulless drudge. She must have a certain modicum of culture. She should have sufficient grace and poise to turn the bitter things of existence into lessons of reasonableness and understanding. She should have a generally optimistic viewpoint. She must, of course, be married. Her husband and children should be nice enough to round out the normalcies of her setting. She must have worked before marriage. Only thus could she have assimilated her sense of money values, together with a fitting appreciation of the comforts of home and an adequate realization of her husband’s workaday problems with a consequent compassion for his struggle. She would complete the rhythm of this theoretic structure if she had been that vestal of the American hearth—a schoolteacher.

Checking and re-checking these specifications brought me to the selection of a builder. Like every other idea at the same inarticulate stage, the fate of the design rested on the manner of its execution. This was a job for a woman. It required great objectivism. It demanded unlimited facility for losing oneself without being lost in the very mind and actual manners of another. It would be ghost-writing for a synthetic heroine. Interpretation of a flesh-and-blood principal would be an easy stint in comparison.

Search for a satisfactory candidate for this assignment dragged for months. In her absence, Newspaper Feature Service began its activities without the feature which had been counted on for a headliner. Then fortune pointed to the woman who, in the argot of Broadway, was “the natural” for the story. As Nana B. Springer, she had been the star sob-sister of the Chicago American during my tour as managing editor. Not only had she been an indefatigable worker, but she flashed more journalistic fire than any of the men on the staff. In the stress of an unfolding yarn, she made light of food and rest. It was not unusual for her to snatch a few hours’ sleep on a pile of exchanges in the newspaper morgue.

Once she saved an innocent man from the gallows in Chicago. Jocko Briggs, married, with an infant son, had been convicted of a hold-up murder. Miss Springer, then writing under the nom de plume of “Evelyn Campbell,” became convinced that there had been a miscarriage of justice. Briggs’s lawyer, Robert E. Cantwell, contended that the victim’s dying statement was misunderstood. The expiring man had moaned “Chack! Chack!” Police witnesses had satisfied the jury that he was crying “Jack! Jack!,” the name by which Briggs was known to him. Cantwell asserted that he meant “Check! Check!,” referring to the bank scrip of which he had been robbed. Evelyn Campbell’s energy, driving through the boil of fervent appeals in the American and backed by her well-arranged presentations of fact, brought about a stay of sentence. Then she forced a new trial. Jocko Briggs was finally acquitted.

Pleasing to the eye, with an attractive personality, Nana B. Springer was persuaded to give up journalism for wifehood. She married a fellow reporter, Martin A. (“Matty”) White. The couple moved to New York, where White became general news editor of the Associated Press. Two children had been born to them. It occurred to me that Nana might welcome an opportunity to enhance the funds available from her husband’s salary for her children’s education. My hunch was confirmed. Mrs. Martin A. White resumed journalistic work as Adele Garrison.

That name was made up to hit as close as possible to the median line in the American social fabric. Mrs. White accepted it and all the other sailing directions for her voyage on the serial main with characteristic enthusiasm. She had lost none of the high spirits that carried her through reportorial feats a decade earlier. She exulted over the qualifications that particularly fitted her to fill the shoes of Adele Garrison. Definite affinities linked the fictitious with the real personality. There was even a vocational parallel. Mrs. White had been a schoolteacher in Milwaukee before she became a newspaperwoman.

All this made startlingly incredible the charge of plagiarism subsequently advanced by a competing syndicate. It was the strangest assertion of copyright infringement that ever engaged my professional attention. The complainant was Newspaper Enterprise Association. Originally organized to exchange features among units of the Scripps-McRae League of newspapers, this bureau had expanded into the business of selling its materials to unaffiliated dailies. It developed an extensive traffic in these byproducts.

Notice of Newspaper Enterprise Association’s claim reached me in a formal communication from John H. Perry, then general counsel for the E. W. Scripps interests. It demanded the immediate withdrawal of Revelations of a Wife from distribution “in any form whatsoever.” Failure or refusal would result in application for a writ of injunction. Meanwhile, Mr. Perry’s sorely aggrieved principal was reckoning the extent of the damages that had been inflicted by Newspaper Feature Service, with a view to suing for their recovery and for the assessment of a punitive award.

Portentous as were the contents of this letter, its signature would have been even more impressive some years later when the newspaper operations of John Holliday Perry assumed first-tier magnitude, including Western Newspaper Union and American Press Association, with a combined clientele of approximately 10,000 publications, a chain of dailies in Jacksonville, Pensacola, Panama City, Fla., and Reading, Pa., and other important corporations.

Strenuous investigation yielded no evidence on which to question the sincerity of Perry’s statements. Yet it was impossible to stomach the alleged grievance as sound or genuine. The main allegations were reviewed in my reply to Perry, a condensation of which is given here in brief:

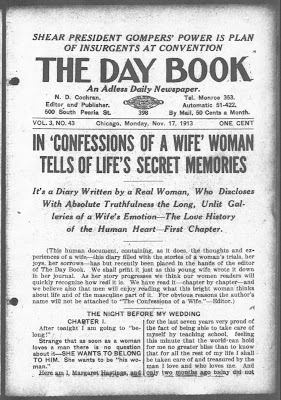

- It is true that Newspaper Enterprise Association is publishing a serial story entitled Confessions of a Wife and that Newspaper Feature Service, Inc., is publishing a serial story entitled Revelations of a Wife.

- It is true that each serial is in the form of a diary.

- It is true that in each case the diary purports to have been written because of a sacred promise to a dying mother.

- It is true that in each case the diarist is red-haired.

- It is true that each diarist was a schoolteacher before her marriage.

- It is true that in both cases the diarist’s first name is Margaret.

- It is true that the first name of the husband of each diarist is Richard.

- It is true that each husband has been an artist.

We have no means at this time of telling whether the Newspaper Enterprise Association serial was inspired by the Newspaper Feature Service, Inc., serial. We do know, however, that any disadvantage growing out of the similarities in the two features must redound to the damage of Newspaper Feature Service, Inc. That conclusion flows from a consideration of the relatively inferior clientele of Newspaper Enterprise Association.

Such conflict as may be discoverable in the two titles tends to cloud the standing of your client. I call your attention to the fact that in 1904, during my managing editorship, the Chicago American published a so-called continued story of married life entitled Confessions of a Wife. It was written by Elizabeth Miller Yorke.

In view of these circumstances, I demand that Newspaper Enterprise Association cease forthwith to publish Confessions of a Wife, since it is at best a poor imitation of our current feature and fails to warrant publication as original matter. 5

Perry’s clear vision showed him that if the controversy were carried to a judicial decision, the contention might turn around the copyright on an angle of unfair competition. The litigation would entail expenses and inconveniences greater than the stake in sight. He chose a Fabian strategy. The issues were never joined at law. Perhaps that omission scored an error against me. However, Revelations of a Wife ran on like the babbling brook, while Confessions of a Wife eventually petered out. The Newspaper Enterprise Association serial, written by Idah McGlone Gibson, was discontinued in August, 1918. By 1941, Adele Garrison’s diary, then appearing under its latest title, Marriage Meddlers, had grossed a syndicate revenue in excess of $750,000. It had earned for the writer something less than a third of that amount. But its financial phases took minor rank beside its social aspects. The same processes that tied its threads into the reading habits of millions of American families also entwined them in the cultural history of the generation.

Footnotes

1 - Clare Briggs was an extremely gifted and inventive writer of comic strips, so Koenigsberg's claim that he created and directed the strip seems almost certainly to be self-congratulatory hyperbole. Unfortunately as far as I know Briggs never commented on this strip to set the record straight.

When Koenigsberg says that A. Piker Clerk was a "serial strip" he means that in addition to it running daily, that it told a continuing story from day to day. With no complete run of the Chicago American in existence, all we can say is that, based on Bill Blackbeard's collection, A. Piker Clerk seems to have not appeared as a true daily, but was more of what I term a 'weekday strip', missing a day here and there. The first daily comic strip, in any case, pre-dates this strip by a few months (The Importance of Mr. Peewee), and it may even qualify as a 'serial' strip.

Bill Blackbeard, used to say that you could not tell for sure about the strip being a true daily, because it frequently ran in only one or a few of the many editions of the American that were issued each day. Therefore, since no one can claim to have a complete archive of the American's many daily editions, no one can say for sure. Though I cast a jaundiced eye on that comment way back then, Koenigsberg's narrative seems to suggest that it may be true -- that A. Piker Clerk may have been used to enhance sales of particular editions.

2 - Although it is true that many weekday strips of that era tended to run in boxed two-tier format, and therefore did not extend across the entire 7-column page, it is patently untrue that it never happened before A. Piker Clerk. Perhaps Clerk can be said to have been the first to consistently run in that format.

3 - It seems utterly bizarre that the king of yellow journalism nixed a comic strip for being vulgar -- especially one that was supposedly such a circulation boon. However, it must be said that Hearst did have a capricious nature, and without any comment from Briggs or other Chicago American almuni, we can to take this statement with a grain of salt, but cannot dismiss it entirely.

4 - I cannot fathom what Koenigsberg is referring to here. In the mid-teens, Hearst had the American and the Journal running in New York, and neither had a horse-track fiend starring in them (Mutt and Jeff, of course, had long since eschewed that genre). The Mirror did not become his third paper there until 1924. Joe and Asbestos, mentioned in the next paragraph, did not become a tip sheet strip until the 1930s.

5 - Koenigsberg should be ashamed of himself to characterize the episode this way. To say that NEA's serial might have been 'inspired' by NFS's is ridiculous - the former started two years prior to the latter. In any case, the title "Confessions of a Wife" and the general gist of both serials is stolen from a serial that began in 1902 in the Century Magazine. Koenigsberg's declaration that the Chicago American ran such a serial in 1904 thus just makes him a serial plagiarist.

Chapter 14 Part 3 in Two Weeks link to previous installment link to next installment

Labels: King News