Saturday, December 02, 2017

Herriman Saturday

June 2 1909 -- Herriman's 'Guess Who' sports series continues, this time highlighting the official timer at one of the local boxing venues.

Labels: Herriman's LA Examiner Cartoons

Friday, December 01, 2017

Wish You Were Here, from Fred Opper

Somehow the Mutual Book Company of Boston, a somewhat cheapsie sort of outfit I gather, got the rights to an Opper postcard image in 1905. Also rather odd that Opper, if he was in fact the author of the caption, chose to appropriate a very similar term to one popularized by his Hearst compadre, F.M. Howarth (Mr. E.Z. Mark). But I doubt Opper chose the caption, because I was able to find one other Opper postcard in this series, and that one appropriates the gag from a popular postcard series of the time "The Whole Dam Family". Seems like the folks at the Mutual Book Company were trying to play piggy-back on proven sellers.

The cartoon itself is a bit opaque to me -- I guess Opper might be saying that oysters served at a church fair are a good bet to make you sick (you're a Mr. Easy Mark). If that's the gag, it seems like the oyster might have been drawn to make it obvious it is noxious. This one looks like a fine upstanding citizen.

Labels: Wish You Were Here

Comments:

Mystery solved. Opper illustrated a book by Eugene Field ...

https://www.amazon.com/Complete-Tribune-Primer-Eugene-Field/dp/1530811309/ref=sr_1_2?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1512167151&sr=1-2&keywords=Complete+Tribune+Primer

... which included a bit about how one oyster is responsible for all the weak oyster stew sold at church fairs ...

https://books.google.com/books?id=gkFLAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA11&lpg=PA11&dq=%22Eugene+Field%22+primer+oyster&source=bl&ots=cWBxeo-afL&sig=Bxkk70EGHF8lwV9vp6h2qyMaqZE&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj1--Xj6-nXAhWE64MKHZomD38Q6AEIRTAM#v=onepage&q=%22Eugene%20Field%22%20primer%20oyster&f=false

The Easy Mark is most likely anyone who buys the oyster stew this fellow is involved with.

Post a Comment

https://www.amazon.com/Complete-Tribune-Primer-Eugene-Field/dp/1530811309/ref=sr_1_2?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1512167151&sr=1-2&keywords=Complete+Tribune+Primer

... which included a bit about how one oyster is responsible for all the weak oyster stew sold at church fairs ...

https://books.google.com/books?id=gkFLAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA11&lpg=PA11&dq=%22Eugene+Field%22+primer+oyster&source=bl&ots=cWBxeo-afL&sig=Bxkk70EGHF8lwV9vp6h2qyMaqZE&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj1--Xj6-nXAhWE64MKHZomD38Q6AEIRTAM#v=onepage&q=%22Eugene%20Field%22%20primer%20oyster&f=false

The Easy Mark is most likely anyone who buys the oyster stew this fellow is involved with.

Thursday, November 30, 2017

King News by Moses Koenigsberg: Chapter 13 Part 2

King News by Moses Koenigsberg

Published by F.A. Stokes Company, 1941Chapter 13

Monsieur Veto (part 2)

link to previous installment link to next installmentThe cycle from 1909 to 1913 was for me an uninterrupted ride on an international merry-go-round. The longest period devoted to any one panoramic segment lasted four months. That was in 1910, my first trip abroad. Farrelly arranged it. Ostensibly, it was a bonus for services rendered to the Hearst syndicate. Incidentally—if not principally—it was intended to gather information regarding a possible English market for the Hearst output. A study of British humor was, perforce, a preliminary to my research.

In high elation, I brought back a covenant of alliance with Henderson Bros., Ltd. A Scotch publishing organization, this firm issued regularly twenty-odd different periodicals for circulation throughout the British Empire. The price of two hundred guineas weekly was fixed for the right to reproduce in the various Henderson editions a selection of Hearst materials in original or revised form. Farrelly was delighted. The opening of this wholly new field suggested many possibilities. But Farrelly’s exhilaration was short-lived. Hearst peremptorily canceled the deal. Why should a British publishing house turn to its profit the talents of his own staff?

The willingness of a successful English magazine company to make such an indenture was, in effect, a guaranty of British hospitality for these newspaper elements. The reasoning may have been sound, but it was not sustained by the outcome. Hearst launched a weekly in London. Its title was The Budget. It contained a number of the comics and pictorial items most popular in the Hearst papers. Efforts were made to adapt them to English tastes.

The Budget was an amusing plaything. Calculated by Hearst’s standards, it was relatively inexpensive. He dropped it before the losses had gone far beyond a quarter of a million dollars. And that was a negligible sum compared with the profits later returned to him by Nash’s magazine and the English edition of Good Housekeeping, both monthlies of the silk-stocking class. British readers, unwilling to spend a penny for Hearst in dominoes, paid sixpence for him in frills.

My quadrennium of journalistic excursions concluded with the most piquant errand that it was my fortune to undertake. For three months I labored in vain to hand over to the leading citizens of San Francisco, then the metropolis of the Pacific Coast, a substantial favor, with worldwide garniture, from their fellow townsman, William Randolph Hearst. The offering snagged on a disbelief in Santa Claus. An unrelenting newspaper rivalry had something to do with the inception of this skepticism.

The Panama-Pacific International Exposition was in course of preparation to open eighteen months later, in 1915. It was to beckon to California visitors from every quarter of the globe. Hearst wanted to make sure that this beckoning attracted the fullest possible attention. He thought that could be accomplished with a campaign of pictures to be distributed throughout the world. Hearst believed that his own facilities for such a dissemination— his newspaper syndicates and services—would exceed those of anyone else likely to be interested in the work. He decided to do the job.

The effectiveness of such a promotional program would depend largely on control of the sources of pictorial supply. This could be commanded through an exclusive right to the use of cameras in connection with the exposition. That would be the photographic concession. It was my assignment to get this. Why the choice fell on me was never explained. Assumably, it was to be followed by the duty of mapping out a distribution system.

My instructions were to guarantee for the privilege a compensation larger than that proposed by any other bona fide applicant. Hearst was giving, not receiving, a boon. No neighbor would be in position to say that he had bargained for an advantage from his native city. This was practically a subvention. How could it be declined? Why had it been considered necessary to send someone across the continent to urge its desirability? Through the answers—as complex as the questions seemed simple—showed some of the strands of that mystic texture from which was woven the unique mosaic of San Francisco’s Hearst and Hearst’s San Francisco.

|

| Michael H. DeYoung |

Gen. Michael H. DeYoung was chairman of the concessions committee of the Panama-Pacific Exposition. He was also the owner of the San Francisco Chronicle. Though born in Missouri, DeYoung considered himself a native son of California. Common nativity with one’s neighbors around Golden Gate meant much more than a social coincidence. It spelled an incantation. It laid upon those within this magic circle an inviolable obligation to unite against the outsider. But nothing in this union relieved a member of the need to protect himself from every angle and shadow. And during my sojourn in San Francisco, angles and shadows appeared to enjoy the special auspices of the marvelous California climate. They sprang up everywhere. General DeYoung was disconcertingly courteous. He seemed worried about my safety. His secretary was permitted to whisper an explanation. The general expected me momentarily to be trampled by the Trojan horse I was leading.

Thrusts from the rear complicated my mission. The former superintendent of police, Fred Esola, announced himself as an associate of Andrew M. Lawrence in an application for the photographic privileges. Only a few years before, Lawrence had been chief executive of the San Francisco Examiner. Now he was Hearst’s agent in the Middle West, and the pull of his relationships was still to be reckoned with in California. Some heads of the exposition company were uncertain whether to fear or to favor him. But it was easier to dislodge Lawrence as a contender than to overcome the negative influence of the resident Hearst viceroy.

Dent H. Robert, once my city editor on the St. Louis Republic and currently publisher of the San Francisco Examiner, found nothing to approve in my presence. It was an intrusion. There was something of the Pharisee in Robert. He was especially intolerant of Hearst men employed east of the Rockies. Most of them, he felt, were parasites subsisting on the wealth that was siphoned from Hearst’s West Coast profits. He believed Hearst had been adequately represented in California before my arrival. He didn’t feel that my coming had bettered this representation. Robert was rather explicit on that score during a wrangle with me. The quarrel occurred in the hearing of several Exposition committeemen.

Hearst did not get the photographic concession for the Panama- Pacific International Exposition. A time limit for the acceptance of his proposal was permitted to lapse. Three months after my return East, a committee of regretful San Franciscoans came to New York. They wanted to revive Hearst’s interest in the project. Maybe there was a strain of Santa Claus in him, after all. My cooperation was requested. It was not painful to say, “Too late.”

There would be small point to the recollection of these trivia if their significance related only to the camera privileges at an international fair. They make an integral chapter of a life that repeatedly touched world crises. In these circumstances, with kindred manifestations, was contained my solution of the engrossing Hearst riddle—the nature of his influence on public opinion. This explanation indexed the amazing fluctuations of that force. It dissected a power capable of pivoting a national movement, yet incapable of budging a city’s electorate. It reckoned the potentialities of a private citizen who might balk presidents, premiers, emperors or dictators while being himself balked by petty local bosses. It traced the phenomenon of a recurrent factor in world affairs incurring futile failures in county politics; Hearst’s major share in campaigns affecting international treaties contrasted with his defeats in municipal contests.

To Hearst must be attributed the breaking up of more political careers than crumpled under the assaults of any contemporary. One need search no farther for that record than a single performance— the publication in 1908 of letters of John D. Archbold, vice-president of the Standard Oil Company. The result went far beyond the discrediting of United States Senators J. B. Foraker and Marcus A. Hanna of Ohio, Boies Penrose and Matthew Quay of Pennsylvania, and Joseph W. Bailey of Texas. It smashed one of the strongest cabals that ever infested our Congressional branch of government. The fact that the correspondence was stolen did not lessen the effects of the exposure.

Crooked politics underwent a memorable setback. But encomiums did not hush the execrations. That was owing mainly to the mode of attack. It stimulated conjecture regarding Hearst’s motives. It gave color to his enemies’ charge that he was more interested in advancing his individual program than in serving the public. It is true that he reserved the Archbold revelations for a special purpose. They punctuated his advocacy of his handmade party and presidential candidate—the Independence League and Thomas L. Hisgen. But that didn’t mar their validity.

Hearst has suffered from the acid reactions of his aggressiveness. He was an explorer of turpitude—of the shadows of sinister or ulterior designs to which he pointed behind nearly every shining light. He inculcated distrust. The counsels for suspicion, that he so forcefully and so continuously directed toward others, now and then turned against himself. In the backwash of currents whipped by his methods, some of his own magnanimities foundered. We have seen his neighbors decline his donation of money and services.

The average intelligence clings to unities. Hearst’s activities were unified in the prevalent understanding with breaking up rather than building up social elements. Superman in political demolition, he. was described as “The Great Wrecker.” The characterization clicked in millions of minds. Hosts hastened to help him tear things down. Few tarried to build anew. That has been the popular custom through the ages. It would be a mistake to think Hearst had wholly lost their allegiance when his followers ignored his summons for special labors. Again and again he rallied the same or as many adherents as before, though they mustered not to toil in the fields, nor yet to tend the flocks, but always and apace to smite the Philistines. Monsieur Veto, after a lapse of a century, once more became a realistic title. Louis XVI gained it through legislative action. Hearst won it through the prowess of his pen.

“The Great Wrecker” bore a connotation more of honor than of opprobrium. The devastation it implied was limited to quarters undeserving of sympathy. Otherwise, it could not have been wrought. Only structures honeycombed with culpability can be destroyed by the light of publicity. Their removal is less an engineering than a sanitary function. Hearst, having performed an Augean renovation, might well—if he chose—swap the appellation “The Great Wrecker” for “The Great Sweeper.”

In any case, Hearst held regularly the sustained interest of more of his fellow citizens than was commanded over the same span of time by any American outside the White House. Even if this attention were convertible only into one-way dynamics, it was inalienable from Hearst. It maintained his publications in a group supremacy unattained by any of his rivals. The sum total was a record without contemporaneous parallel.

~ ~ ~ ~

Whether because of training or of a quirk of providence, it has been my experience to be driven to deeper introspection by minor annoyances than by major crises. Important events usually clamped upon my emotions the stern rule of reason, while a petty nuisance prodded an impatient search for the cause of corollary irritations. Realism paved its own firm roadbed. Subjectiveness rode on wobbly rails. So, vexations of the unsuccessful mission in San Francisco led to another survey of my affairs. It was not gratifying. Four years of a unique occupation were drawing to a close. There had been plentiful luck and excitement in hunting, trapping and fishing for journalistic game and in plowing newspaper and adjacent fields. But there was not a bag, a catch or a crop for myself. Bull’s-eyes had been scored often enough, but the trophies were not awarded to me. It was like a travel schedule that embraced all directions with no arrival.

The time had come long since to choose a definite destination. A drastic step was necessary to enforce the choice. There must be a severance of the connection that had kept me drifting. My resignation was forwarded to W. R. Hearst. Twice before in the previous two years, I had resigned. Once, Farrelly persuaded me to remain to work out an especially intriguing problem of telephone news circuits. The second time, the vulgar attraction of more money induced the renewal of my personal service contract. My compensation was increased to $150 weekly. Now, there must be something besides a salary advance to hold me.

If the mettle were in me to reach the top, it must be proved without further delay. My thirty-fifth birthday was approaching. At that age, a journalist should be either aboard or underneath the chariot of destiny. Few men in my profession had undergone a more thorough training for main-event contests. Either my hand was already fitted for the handle of a first prize or it was doomed always to rummage through the grab sack. This must be determined by my next venture.

The doors of one arena stood invitingly open. The newspaper feature syndicate offered measureless opportunities. Most attractive was the absence of time barriers. Signal achievement was possible almost overnight. Practically no capital was needed for plant investment. An organization to serve hundreds, even thousands, of publications could be set up with less cash or labor than would be required to launch one daily. Highly alluring was the expanse of operation. Its limits were fixed only by the merits of the output—the effectiveness of the materials designed to challenge and hold readers. State lines didn’t dim the sparkle of ideas.

The problem of finances had been solved before it arose. The solution was entwined in the gratitude of a publisher who believed it was my advice that had turned a steady loss into an annual profit of $200,000. This over-appreciative friend was Rafael R. Govin. He then owned El Mundo and La Prensa in Havana, Cuba. Later, he added to his string of publications the Post and the Telegram in Havana, the Advertiser and the Telegram in Elmira, N. Y., and the Journal of Commerce in New York City.

Our acquaintance, beginning in Chicago, ripened into a lasting cordiality. It was Govin who, in 1905, authorized me to offer to the City of Chicago an immediate conversion of its street railway system into municipal ownership. At that time he represented the local traction trust. Gradually, he withdrew from the money marts. Our intimacy grew with each step that he took away from Wall Street. Now, early in 1913, he proposed a business partnership. He would supply the funds for the installation or purchase and operation, under my management, of either a news service or a newspaper.

My plans for a syndicate, long in incubation, won Govin’s enthusiastic approval. He regarded such a business as a modified news service. At any time we chose we could expand our activities and add telegraph or other transmitting devices. On my estimate of the sum necessary to safeguard success, he agreed to make available in suitable installments over a period of thirty months, a bank credit of $150,000. Fifty-one percent of the stock would be deliverable to me at a price to be determined by the amount of the aggregate cash investment. Govin worked out a sliding scale exceedingly generous to me. There was no haggling. He expected handsome dividends and he wanted to stimulate my efforts to hasten them.

The conversation that assumably closed the deal with Govin took place ten days after the posting of my resignation to Hearst and three days after my return from San Francisco. That was in February. The date of expiration of my last indenture was two months earlier. Not the slightest doubt occurred to me about complete freedom to devote myself to any work I might choose. Formal announcement of my severance from the Hearst organization had been prepared. It was intended for the scores of publishers and editors who, from time to time during the previous four years, had indicated interest in my plans for the future. It would be the first gun in a campaign for promotion of the syndicate on which I had resolved months earlier. The cards were in the mails before the conclusion of my conferences with Govin. The Rubicon was passed—but not triumphantly. My agreement with Govin was unexpectedly spiked.

Under an interpretation of law by the New York State Court of Appeals, I was still bound to Star Company, the Hearst holding corporation. The rule was little known. It stipulated that a continuance of relations at the end of a personal service contract might be construed as a renewal of that instrument. Thus, either the payment or the acknowledgment of compensation restored the compact. There had been no interruption of my salary. Therefore, my contractual obligation was binding ten months longer, the remainder of the year.

Notification of my status came from Carvalho. He seemed to get a treat out of my surprise. His statement smacked a good deal of pedantry. The master enjoyed demonstrating a ligature hitherto unknown to the interne. But Carvalho was conciliatory. It was at this meeting that he extended the olive branch. Our business relations thereafter were uniformly pleasant and—to me —stimulating. There had been no design to trick me, he said. On the day my farewell letter to Hearst was written, Carvalho had received instructions to arrange a new assignment for me. Its delivery was timed for my return from the West Coast. That was done to avert any leakage of the facts—Carvalho’s inescapable obsession—and to perfect certain preliminaries.

A wrench came with the recollection of the engraved notices that were speeding to a long list of my newspaper friends. How could that be explained? It would be stultifying enough to affect my usefulness. Carvalho tossed that thought out of the window. What I had done fitted most happily into the plans for the enterprise to be entrusted to me. It would be just as well to face the world as a former member of the Hearst family. Indeed, that course was highly recommended. My work would be performed in complete independence of the Hearst establishment. The success of the project would be determined by the degree of vigor that entered into its rivalry. Mr. Hearst wanted me to organize and operate a new feature syndicate!

Here was a stretch of coincidence to strain its longest reach. There could have been no deliberate synchronization of these incidents. The facts seemed obvious. Yet they got snared in the gullet of credibility. They left a lingering urge to peek under desk pads and table covers. Consideration of Hearst’s motive brought one no closer to the point of this poser. Why should he create and support a competitor? Carvalho had a convincing explanation. But it wasn’t complete. It required several years to envisage the full meaning of this novel strategy.

Carvalho outlined Hearst’s purpose to insure against a let-down in the production of features—not so much in quantity as in quality. Normal incentive wasn’t adequate. It might languish under decreasing pressure from other publishers who didn’t share Hearst’s insatiable desire for more and better elements of newspaper entertainment. He would have two teams on the field instead of one. No race would be thrown, because each crew would strive to its uttermost to surpass the other. Nothing would be permitted to divert the paramount purpose of keeping both squads on edge. Concurrently, Hearst would enjoy an undisclosed vantage in the discovery and development of new talent.

Despite the attractive aspects of Hearst’s syndicate program, it did not turn me from the resolve to secure a proprietary share in both the direction and the fruits of my labors. Unwillingness to work for a regular stipend should disqualify any employee. A candid declaration of this attitude should bring about my separation from the Hearst payroll and thus permit the carrying out of my arrangement with Govin. But Carvalho had a persuasive rejoinder. It was purposed to allot to me the equivalent of a partial ownership. And this would not involve any pecuniary risk on my part. Mr. Hearst wanted me to receive a percentage of the profits. Since that would constitute a portion of my remuneration, there would be no interference with my management. Otherwise grounds might arise for claims that my emolument had been impaired by faulty judgments. My proprietorship might be limited, but my authority would be undivided. I would be my own boss. That was my goal. Yet now that it lay at arm’s length, it gave me no thrill. It was a second choice. There would have been a higher lift in breasting the tape the hard way with Govin. And it was still for him to determine what course I should follow.

Govin was one of those rare mortals in whose presence friendship became an altar at which one felt it a high privilege to stand beside him. First, he released me from any pledge to him. Then he proposed the reinstatement of our agreement as a dormant covenant to be revived at my instance at any time within three years. I was free to carry through the Hearst project with the comforting knowledge that a desirable anchorage lay to windward.

An incorporation certificate was issued to Newspaper Feature Service by the State of New York on August 16, 1913. The usual formalities installed me as president and general manager. The syndicate’s first release of features appeared in newspapers of Sunday, September 7th. Of course, many weeks had been devoted to their preparation. They initiated a service to which may be traced appreciable effects on the reading habits of America.

Chapter 14 Part 1 Next Week

link to previous installment link to next installment

Labels: King News

Wednesday, November 29, 2017

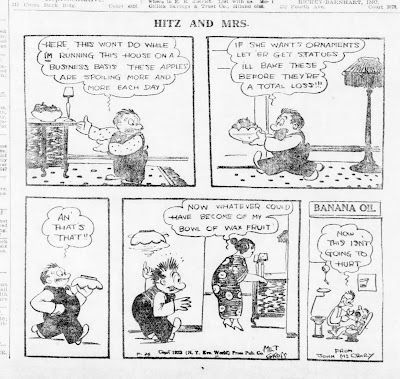

Obscurity of the Day: Hitz and Mrs.

Starting at the end of 1923, Milt Gross embarked on a long and almost unbroken run of very successful comic strip titles -- Banana Oil, Nize Baby, Count Screwloose of Tooloose, Dave's Delicatessen, That's My Pop, and others. One of his last brushes with obscurity was with the series Hitz and Mrs., which ran from April 9 to December 29 1923. It was produced for Pulitzer, where he would stay until he jumped ship to Hearst in 1930.

While Hitz and Mrs. did not set the syndication world on fire, Gross was definitely beginning to hit on all his comedic cylinders. Fowler Hitz and his better half are prototypical Gross shlemiels, even if Gross was not yet letting his Yiddish hang out in public view. The raucous gags and sometimes bizarre humor are prototypical Gross.

On October 27, Gross added an extra panel cartoon to each installment, titled Applesauce. The term was contemporary slang that was an expression of incredulity and disbelief. In other words, if the used flivver salesman told you that a car was only driven by a little old lady to church on Sundays, your response would be "Applesauce!". This panel cartoon went on for a month, until Gross had an even better idea. Instead of the existing slang term, he'd invent his own equivalent. On the strip of November 26 and thereafter, the panel was renamed Banana Oil, and an idiom was born. Here's the first strip to use Gross' newly minted bit of slang:

On the final week of Hitz and Mrs., Mr. Hitz keeps getting handed a piece of paper that says "Banana Oil" on it. This was Gross' equivalent to a pink slip for the Hitz duo, and the next week he dumped the Hitz family and renamed the strip to Banana Oil.

I do wonder why Mr. Gross happened to pick this term. Oddly enough, banana oil is actually a real thing. It is the common name for the chemical compound isoamyl acetate. This somewhat nasty chemical, which can be produced from banana plants, is used in low concentrations to flavor foods. In higher concentrations it is used as a solvent, in making brass coatings, and for stiffening aircraft surfaces. In newspapers of the day, you can find advertisements offering it for sale, and occasional news articles in which it is blamed for making people very ill from the fumes.

Labels: Obscurities

Comments:

I don't know if you can see this, but here's the sheet music cover to "Banana Oil," with of course a Milt Gross drawing.

https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=1797851753591137&set=a.136911183018544.16901.100000989880370&type=3&theater

https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=1797851753591137&set=a.136911183018544.16901.100000989880370&type=3&theater

Could that dentist gag on the first "Banana Oil" panel have been suggested by the infamous John "Scarfoot" McCrory? McCrory was an early film animator who worked in the style of Paul Terry. He did a cartoon series in the early 1930s in sound, called the "Krazy Kid" cartoons.

Post a Comment

Tuesday, November 28, 2017

Ink-Slinger Profiles by Alex Jay: Norman Anthony

Norman Hume Anthony was born on May 11, 1889, in Buffalo, New York, according to his World War I and II draft cards. Hume was Anthony’s mother’s maiden name.

In the 1892 New York State Census, Anthony was the youngest of three children born to Edward and “Lettie”. Anthony’s father was a grain merchant. They lived in Buffalo.

The 1900 U.S. Federal Census recorded the family of five and a servant in Buffalo at 111 Morris Avenue. Anthony’s mother’s name was Electa. The same address was in the 1905 state census which included Anthony’s maternal grandmother, Margret Hume.

Anthony attended Lafayette High School. The Buffalo Courier-Express, April 12, 1931, profiled Miss Elizabeth Weiffenbach, artist and head of the art department at Lafayette. Anthony was a cartoonist on the school paper, The Oracle. The Courier-Express, March 21, 1926, profiled Anthony who said, “I went to Lafayette high school, and had athletic ambitions there on the track….Guy Hoff, the artist, was in my class, and we studied art together under Urquhart Wilcox at the school of the Albright art gallery.”

According to the 1910 census, Anthony lived with his parents in Buffalo at 103 Highland Avenue. His father worked at a fire insurance company.

The Courier-Express, August 29, 1911, noted Anthony’s marriage.

On June 5, 1917, Anthony signed his World War I draft card and said his address was 317 West 95 Street in Manhattan. The self-employed artist claimed an exemption because of a “floating kidney” condition and his wife’s dependence. His description was medium height, slender build with blue eyes and blonde hair.

American Newspaper Comics (2012) said Anthony produced Private Dobb’s Diary from March 4 to December 6, 1918 and it appeared sporadically until early January 1919. The series was distributed by King Features Syndicate.

Anthony’s address was unchanged in the 1920 census which counted him, his wife and daughter Edith. Anthony was a self-employed artist.

In 1922, Anthony joined the staff of Judge magazine. The Courier-Express’s profile of Anthony said

Magazine editor Anthony, Margaret, Edith and eight-year-old son, Norman Jr., resided at 58 Highbrook Avenue in North Pelham, New York, as recorded in the 1930 census.

Another Anthony profile appeared in the June 26, 1932 edition of the Courier-Express. Anthony gave up writing fiction to become editor of another humor magazine.

Anthony wrote the book for Ballyhoo of 1932 and was one of four directors including Russell Patterson.

Anthony arrived in the port of New York on November 8, 1932. He visited Europe and departed Le Havre, France six days earlier.

Anthony’s The Drunk’s Blue Book was illustrated by Otto Soglow and published by the Frederick A. Stokes Company in 1933.

Anthony’s mother-in-law, Christine Hofheins was part of the household in the 1940 census. The apartment building was in Pelham, New York at 127 Fifth Avenue. Anthony continued as a magazine editor and his daughter was a magazine publicity clerk.

During World War II, Anthony resided in Manhattan at 18 Gramercy Park. His business was the Anthony Publishing Company, 11 West 42nd Street, New York, New York. When Anthony signed the card, on April 27, 1942, he was five feet ten inches, 140 pounds, with blue eyes and gray hair.

The book for Bright Lights of 1944 was by Anthony and Charles Sherman. The Broadway musical had four performances.

Duell, Sloan and Pearce published two books by Anthony. First, in 1946, was How to Grow Old Disgracefully followed by What to Do Till the Psychiatrist Comes in 1947.

Anthony visited the Bahamas in April 1947. He returned to New York on the 24th. His address on the passenger list was 17 Gramercy Park, New York City.

Anthony passed away January 12, 1968. The Times’ obituary said Anthony died at Hudson State Hospital in Poughkeepsie, New York. Death was attributed to emphysema with complications that led to a heart attack. Anthony was living with his son at Travis Corners Road, Garrison.

—Alex Jay

In the 1892 New York State Census, Anthony was the youngest of three children born to Edward and “Lettie”. Anthony’s father was a grain merchant. They lived in Buffalo.

The 1900 U.S. Federal Census recorded the family of five and a servant in Buffalo at 111 Morris Avenue. Anthony’s mother’s name was Electa. The same address was in the 1905 state census which included Anthony’s maternal grandmother, Margret Hume.

Anthony attended Lafayette High School. The Buffalo Courier-Express, April 12, 1931, profiled Miss Elizabeth Weiffenbach, artist and head of the art department at Lafayette. Anthony was a cartoonist on the school paper, The Oracle. The Courier-Express, March 21, 1926, profiled Anthony who said, “I went to Lafayette high school, and had athletic ambitions there on the track….Guy Hoff, the artist, was in my class, and we studied art together under Urquhart Wilcox at the school of the Albright art gallery.”

According to the 1910 census, Anthony lived with his parents in Buffalo at 103 Highland Avenue. His father worked at a fire insurance company.

The Courier-Express, August 29, 1911, noted Anthony’s marriage.

In the presence of a few intimate friends, the wedding to Miss Maragret E. Hofheins, daughter of Mr. and Mrs Edward a Hofheins of Woodward avenue, and Norman H. Anthony was quietly solemnized on Friday afternoon in St. Paul’s church, the Rev. Charles Broughton officiating. Miss Elizabeth J. Meldrum was the maid of honor and Harold C. Coppins was the best man. Mr. Anthony is a son of Mr. and Mrs. Edward L. Anthony.At some point the couple moved to New York City. The 1915 state census said cartoonist Anthony and his wife resided in Manhattan at 870 West 180th Street. The family tree said Anthony studied at the New York Art Students’ League.

On June 5, 1917, Anthony signed his World War I draft card and said his address was 317 West 95 Street in Manhattan. The self-employed artist claimed an exemption because of a “floating kidney” condition and his wife’s dependence. His description was medium height, slender build with blue eyes and blonde hair.

American Newspaper Comics (2012) said Anthony produced Private Dobb’s Diary from March 4 to December 6, 1918 and it appeared sporadically until early January 1919. The series was distributed by King Features Syndicate.

Anthony’s address was unchanged in the 1920 census which counted him, his wife and daughter Edith. Anthony was a self-employed artist.

“The Gold Brick Twins” by Irvin S. Cobb in the Brooklyn Standard Union, 4/24/1921

In 1922, Anthony joined the staff of Judge magazine. The Courier-Express’s profile of Anthony said

Anthony became editor of the magazine [Judge] in 1923. He describes his task as the “grim job of being funny.” His duties consist in reading something like 300 or 400 jokes every day, and selecting from this vast mass of material the jokes that are both new and interesting. Every other week a special number is published, in which all the jokes relate to the special subject.Anthony left Judge in 1928 to become editor of Life until 1930 when the Depression took its toll on the magazine.

…He must cast around for a subject, think up funny cracks about it, and direct the efforts of his large staff of artists and jokesmiths in working up these ideas into printable form. He has arranged humor into a system. He passes out the subject for the coming special issue on one day. On another, the artists submit their ideas and sketches; on a third day, the jokers appear with their jokes, and Anthony selects the best ones for further treatment and eventual publication.

Magazine editor Anthony, Margaret, Edith and eight-year-old son, Norman Jr., resided at 58 Highbrook Avenue in North Pelham, New York, as recorded in the 1930 census.

Another Anthony profile appeared in the June 26, 1932 edition of the Courier-Express. Anthony gave up writing fiction to become editor of another humor magazine.

Norman Anthony admits he doesn’t know how Ballyhoo came into existance [sic] but it was something like this: George T. Delacorte, Jr., publisher and owner of Film Fun, offered him $600 to prepare the first issue of a funny magazine, any funny magazine, if he could do it at an additional cost of another $500. A friend of his told us that at this point Norman Anthony promptly sat down and wrote and illustrated the entire first issue of Ballyhoo on a window-sill. He says he did do it all, but not on a window-sill. Very likely it was on the spur of the moment.Ballyhoo was published from August 1931 to February 1939. The New York Times, January 22, 1968, said, in an obituary, Anthony went on to create Hellzapoppin’, Der Gag Bag and The Funny Bone.

Anyway, the publisher was delighted, and made him a partner, though he did object at first to a magazine burlesquing ads. Objection over-ruled. One hundred and fifty thousand copies of that first issue were sold, and the circulation of Ballyhoo has since reached and exceeded 1,000,000 copies.

Anthony wrote the book for Ballyhoo of 1932 and was one of four directors including Russell Patterson.

Anthony arrived in the port of New York on November 8, 1932. He visited Europe and departed Le Havre, France six days earlier.

Anthony’s The Drunk’s Blue Book was illustrated by Otto Soglow and published by the Frederick A. Stokes Company in 1933.

Anthony’s mother-in-law, Christine Hofheins was part of the household in the 1940 census. The apartment building was in Pelham, New York at 127 Fifth Avenue. Anthony continued as a magazine editor and his daughter was a magazine publicity clerk.

During World War II, Anthony resided in Manhattan at 18 Gramercy Park. His business was the Anthony Publishing Company, 11 West 42nd Street, New York, New York. When Anthony signed the card, on April 27, 1942, he was five feet ten inches, 140 pounds, with blue eyes and gray hair.

The book for Bright Lights of 1944 was by Anthony and Charles Sherman. The Broadway musical had four performances.

Duell, Sloan and Pearce published two books by Anthony. First, in 1946, was How to Grow Old Disgracefully followed by What to Do Till the Psychiatrist Comes in 1947.

Anthony visited the Bahamas in April 1947. He returned to New York on the 24th. His address on the passenger list was 17 Gramercy Park, New York City.

Anthony passed away January 12, 1968. The Times’ obituary said Anthony died at Hudson State Hospital in Poughkeepsie, New York. Death was attributed to emphysema with complications that led to a heart attack. Anthony was living with his son at Travis Corners Road, Garrison.

—Alex Jay

Labels: Ink-Slinger Profiles

Monday, November 27, 2017

Obscurity of the Day: Private Dobb's Diary

Private Dobb's Diary is a mite text-heavy to qualify for Stripper's Guide as a cartoon panel, but it gets at least an honorary pass onto our hallowed grounds because of the creator. Norman Anthony, as far as I know, only created this one newspaper cartoon series. However, he later became extremely notable in the world of cartooning as the editor of the old humor Life magazine, Judge magazine, and as creator of the superb and groundbreaking Ballyhoo. After the humor magazine market dried up, he wrote several bestselling humor books, including the autobiographical How to Grow Old Disgracefully.

Private Dobb's Diary was a daily panel syndicated by Hearst's still very young King Features Syndicate imprint. With our young men being drafted to go over and fight the Hun in World War I, military features were extremely popular. Anthony's entry in the genre, though, seemed to not garner much interest, and I have yet to find it appearing anywhere other than the Pittsburgh Press. It ran there daily from March 4 to December 6 1918, then appeared sporadically until early January 1919. Since the copyrights of the late entries are all in 1918, I'm guessing that the feature did end sometime in December, maybe on the 14th.

On March 4's episode young Dobbs is already in camp, leading me to wonder if the Post picked up the feature late. A copyright entry mentions a date of February 23 (a Saturday), leading me to guess that the real start date of the feature is likely to be February 18.

Labels: Obscurities