Saturday, February 08, 2020

What The Cartoonists Are Doing, November 1915 (Vol.8 No.5)

[Cartoons Magazine, debuting in 1912, was a monthly magazine

devoted primarily to reprinting editorial cartoons from U.S. and foreign

newspapers. Articles about cartooning and cartoonists often

supplemented the discussion of current events.

In November 1913 the magazine began to offer a monthly round-up of news about cartoonists and cartooning, eventually titled "What The Cartoonist Are Doing." There are lots of interesting historical nuggets in these sections, and this Stripper's Guide feature will reprint one issue's worth each week.]

THE MODERN CARTOON

From the Portland Oregonian

When it is declared that there are nowadays no great cartoonists or illustrators, it ought to be recalled that the conditions controlling the art of newspaper caricature and pictorial lampooning are not what they were fifty, or twenty, or even ten years ago. Let us go back no farther than Thomas Nast, who was the most famous, and usually regarded as the greatest, of all American cartoonists. Mr. Nast's first and only notable work was with Harper's Weekly. During the Civil War, a tremendous episode in our history, he began his work. No one who has examined the usual political and personal caricatures of that day can fail to note their wretched and brutal character—miserable as art productions and savage in spirit and expression. Mr. Nast did much to make the profession of the caricaturist respectable. His talents as an artist were considerable, but his insight into affairs, his understanding of the motives of men, and his ability to give them pictorial form are the real secrets of his power.

There was no rival for Nast. He was alone in a field practically untilled. He rarely drew more than a single cartoon a week, and it is easy to see that he had ample time for the study of events and for the full play of his genius. To a great extent the weekly drawing of Nast was inspirational, for undoubtedly he was a man of temperament as well as a student of current history. He was not called upon for a daily offering, and he was therefore not oppressed by the exacting and remorseless grind of daily journalism.

When Nast left Harper's Weekly, after years of remarkable service to his employment and to the cause of truth and decency in public affairs, he made no impression through his contributions to the newspapers. His vogue was gone. He died a heartbroken man. It is an open question whether he might not have sustained his great reputation if he had remained with Harper's. In his latter days other caricaturists had come to the fore and Nast and Harper's no longer enjoyed a monopoly in that line.

Who looks nowadays to an American weekly for a cartoon? Originally the newspaper had no pictures or illustrations and did not have them for many years after they were a feature of the weeklies and monthlies. But with the discovery of a practicable process of newspaper illustration, and with its development through the adaptation of engraving and other methods to newspaper needs, the place of the weekly and the magazine was almost wholly taken by the newspapers, so far as illustration of current events is concerned. Yet it is true that in Great Britain the cartoon remains the peculiar possession of the weekly, and it is the same in Germany. There is a wide difference, however, in the German and British methods, for the Briton seeks to make of his cartoon an elaborate work of art, and the German confines himself to simple lines and memory impressions. The Englishman often uses models and excels as a draughtsman. The German burlesques his subject, and strives for humorous and grotesque effects. So does the American, though there is in this country a wide variety of style and treatment. There is no real American school, as there is a British and a German school. But there are thousands of American cartoonists giving the public their daily output, and making their appeal on every possible subject of human interest.

There is now no Thomas Nast of American journalism. Under our conditions it is doubtful if there could be. But there are a great many fine artists drawing good cartoons and excellent cartoonists making pictures that could by no stretch of the imagination be called sound art. No one, for example, would describe John T. Mc Cutcheon as a true artist, but who has not enjoyed his remarkable contributions to the pictorial literature of American life in all its prominent phases?

It would be easy to name others who are doing good work. On the whole, the average is very high, and certainly an irreparable loss would be suffered by journalism if the services of the cartoonist were to be dropped. The cartoon has come to be an effort to editorialize in a picture the current daily feature of the news or of public thought. The old cartoon—the Nast picture —was a complex affair, always with a central theme, but with many figures and contributing or incidental suggestions. Now it is different. The modern cartoon is a simple thing, with one idea. It requires no study to understand its meaning or to comprehend its scope. It can be absorbed at a glance. It may not be art, but it is something even better. It is the symbol of a truth.

KING'S UNCLE SAM AGAIN

A Rev. M.R. Todd, of Elvaston, Ill., writes to the Chicago Tribune complaining about Frank King's “insipid, unpatriotic, unmanly cartoons.” Mr. King, specimens of whose work are reproduced elsewhere in this magazine, has created a “new” Uncle Sam, flabby and corpulent and rich. Says the Tribune in reply to Mr. Todd:

“The cartoons of Mr. King are correct representations of Uncle Sam as he really is. They might possibly indicate a little more amiability and moral quality, both of which the spirit of this nation possesses. They could not possibly exaggerate the fact that our idealized Uncle Sam requires more tape to measure his waist than his chest.

“It is in a way immoral for this nation to continue to regard itself as typified by a gaunt, muscular, forgiving, but powerful figure, slow to wrath but dreadful in it; able, when aroused in just cause, to admonish and punish the lesser and brawling nations of the earth.

“That is the favorite Uncle Sam of the American imagination, and he is in truth a dreadful figure—but dreadful to the persons who believe and trust in him.

“The lovers of a defiant Uncle Sam are the persons who never think of themselves as sustaining a bullet wound in the abdomen. That bullet is to rip open some other abdomen, and they are to live in the gratification of a pleased dignity.

“The Rev. Mr. Todd's subscription does not expire for nearly a year. If he will continue that long we promise him that the cartoons of Uncle Sam will record any improvement made in the shape and disposition of Uncle Sam. We hope, knowing what new spirit is filling the American people, that by August, 1916, Uncle Sam will be not a bit less just and peaceable, but a terrific lot more able to make his righteous indignation effective.”

To which the Milwaukee Sentinel adds:

“Cartoonist King has invented an 'Uncle Sam,' new style; a figure of Falstaffian girth and obese unfitness for anything in the way of a physical encounter, to take the place of the lean, powerful and sinewy 'Sam' and ‘Jonathan' of the stock cartoon, slow to anger, but terrible as Achilles and fit to whip his weight in wildcats, when roused.

“Mr. Todd considers it 'unmanly and unpatriotic' to portray Uncle Sam as fat and helpless.

“But what about the fact, Mr. Todd? Would 'twere otherwise. The thing to do is to make it otherwise; and to impress it on this nation that it must be made otherwise, and that is the end and purpose of the offending cartoons. Mr. King is telling some hard truths in a galling and rather ribald but effective way.”

THE CASE OF THE CARTOONIST

From the Chicago Tribune

Cartoons in newspapers are reasonably faithful indices of the political thought of the nation. They are theoretically directed in their appeal toward the entire circulations of newspapers, and they are designed to influence thought quickly.

But newspaper cartoons point out more than favorite policies; they indicate more than the specific opinions of the groups which make up the nation; they offer a clew to more than passing squabbles over immigration and neutrality, over national defense and extra-national trade. By their manner, their technique, they go to the bedrock of our democracy.

The cartoonist touches subjects which everyone talks of. But he assumes nothing as to the intelligence of the person he addresses. Out of the far west comes a graphic treatment of the desolate situation of national defense. Mr. Wilson, labeled, is standing in a gymnasium. In his hands is a medicine ball, labeled “preparedness.” He is about to throw it to Uncle Sam, labeled, who is extending his two arms, labeled “army” and “navy,” respectively. In the gallery is Bryan, labeled. On the wall in the form of the rules of the gymnasium is the phrase, “An ounce of prevention,” etc. On the floor is a book which by its label concerns self-defense.

This is not the only cartoon of the kind. The country over these same intricate, explicit drawings go forth by the thousands every day. An English cartoonist would assume that the whiskers of Von Tirpitz would identify him. The American will label him, will label the kaiser, Wilson, Bryan, anyone, every detail. The practice is virtually universal, and it raises the query whether the cartoonist has the public wrong or right. If he has it right it is still in the nursery playing with blocks. The real power of the cartoon is that its symbolism does not require exposition. That is ignored.

One difficulty may be that this nation has few types. The cowboy is fast departing; the ward boss, and the Boston child, etc. The cartoonist is handicapped by his medium. There are few explicit symbols.

The labeling of the obvious may be justified by experience. If it is we must accept a disconcerting theory of American intelligence. It would be pleasanter to think that the lack was in the cartoonist. The obvious may appear mysterious to his timidity. Otherwise this is yet a nation of parishes in which even Mr. Wilson, Mr. Roosevelt, or Mr. Bryan cannot expect recognition unless they be labeled or announced.

MURPHY SEEKS PASTURES NEW

J. E. Murphy, for four years cartoonist of the Oregon Journal, of Portland, has left that position to become cartoonist of the The San Francisco Call and Post. The change was made October 1. Prior to his connection with the Oregonian Mr. Murphy was employed on Omaha and Spokane newspapers. He has recently issued a cartoon booklet entitled “Mr. Tourist in Portland and Oregon,” dedicated to the “See Portland First” idea, and devoted to the business and scenic advantages of the Rose City.

FRANK BOWERS RETIRES

Frank Bowers, one of the veterans of cartoondom, has given up his position on the Indianapolis Star, and gone back to his old home in Oregon to become a rancher. Mr. Bowers is a cousin of the late Homer Davenport.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Puck has added to its numerous attractions a weekly cartoon by W. Heath Robinson, the London artist, whose quaint and amusing drawings for the London Sketch have given him a world-wide reputation.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Robert Minor, cartoonist of the New York Call, was one of the speakers at the recent mass meeting in Elizabeth, N. J., for the organization of the Call Boosters’ Club. Mr. Minor illustrated his talk with a series of cartoons designed to promote the interests of socialism.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

James E. Maher has joined the staff of the Milford, (Conn.) Times as cartoonist.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Another lamentable change is noticed, still speaking of the Colonel. The cartoonists have taken to drawing him with those famous teeth concealed by a mustache.— Rome (N. Y.) Sentinel.

NAST'S GRANDDAUGHTER WED

Miss Muriel Nast Crawford, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. W. R. Crawford, of New Rochelle, New York, and granddaughter of the late Thomas Nast, was married September 16 to Donald E. Battey. The wedding took place in the new Crawford residence on Overlook Circle, Beechmont, New Rochelle. Miss Sallie Nast was one of the bride's attendants. Thomas Nast Crawford and Thomas Nast Hill were among the ushers. Mr. and Mrs. Battey will live in a colonial house in Beechmont recently built by the bridegroom for the bride.

“HANSI’S” CRUSADE RECALLED

The death on the firing line recently of Lieut. Baron von Forstner, who gained notoriety as the result of the Zabern incident, recalls “Hansi's" cartoon fight against Germany. It was the stabbing by von Forstner of a crippled shoemaker at Zabern, Alsace, that inspired the Alsatian cartoonist in his anti-German crusade. “Hansi,” it will be remembered, was sentenced by a German court to serve a year's imprisonment, but managed to escape into France, where he is now serving as a lieutenant in the army. The Zabern affair, which occurred in 1913, created much excitement throughout Germany.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Hy Mayer, of Puck, has been visiting the Pacific coast fairs. He has cartooned his experiences for the movies.

“BRINK” JOINS NEW YORK MAIL

Robert M. Brinkerhoff, magazine illustrator and cartoonist, has joined the staff of the New York Evening Mail, and has been drawing the editorial-page cartoons.

“Brink” went from the Cincinnati Post to New York to try his hand at free-lancing, and won recognition by his drawings for Collier's, St. Nicholas, and other magazines. Before coming to Cincinnati he had been on the art staff of the Cleveland Plain Dealer.

“Am trying hard,” he writes, “to get a human note in serious stuff.” Samples of his work reproduced in this issue of Cartoons Magazine will show to what extent he has succeeded.

BRANGWYN’S WAR POSTERS

The Avenue Press of London has issued a series of poster stamps designed by Frank Brangwyn, the British artist, whose work for the Panama-Pacific Exposition has increased his popularity in America. The stamps will be sold for the benefit of certain war charities.

ORR RENEWS CONTRACT

Carey C. Orr, cartoonist of the Nashville Tennessean, has signed a contract agreeing to remain with the Tennessean two years more. Several rival publishers, it is said, were negotiating for his services at the time, including the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

Mr. Orr was born in Ada, Ohio, 25 years ago. For the first 13 years of his life he lived on a farm, then went to Spokane, Wash., where he received his high-school education. After finishing school he took a position in his father's lumber plant. By playing professional baseball on a Canadian team he earned enough money for a course at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts. He joined the art staff of the Chicago Examiner in 1911, and from there went to the Tennessean. His first cartoon for that newspaper had President Wilson as its subject. He was married recently to Miss Cherry Maude Kindel. Mr. and Mrs. Orr live in a pretty bungalow in Belmont Heights. Mr. Orr's cartoons, especially on political subjects, are deservedly popular at Washington, where he is almost as well-known as in Nashville. He is a Mason, and a member of the Rotary Club.

BERRYMAN AS GOLFER

Clifford K. Berryman, cartoonist of the Washington Star, is learning to play golf. A few days ago, according to a writer on the Star, after he thought he was capable of swinging at a ball without breaking his own neck, he stepped out on the green of the Columbia Country Club, all dressed up, with eighteen new clubs and a dozen and a half of brand-new balls.

He swung his driver at a dandelion and nipped its head; then he neatly drove a cigarette butt about thirty feet in the air and seemed to have every chance of making a 200-yard drive from the tee.

He built a fine little sand pile, placed one of those fine new balls upon it and then grabbed his club for business. He had the correct back swing and his eye was on the ball, but when he swooped downward the club head was scarcely within eighteen inches of the ball.

Then he drew back again and made another attempt. He did considerably better, as the distance between club head and ball was reduced to a mere matter of six inches.

However, that did not satisfy him. He next delivered a terrific swipe at the ball, which toppled from its tee and rolled about a foot.

Cliff looked up in dismay. As his face became visible to the occupant of a bench near at hand a voice was heard to say:

“Why, Berryman, is that you? I thought it must be Dr. Grayson.”

The audience was President Wilson. He had gone quietly to the bench to sit down and await his turn to drive.

THE ABUSED POLITICIAN

Cartoonists are too apt to use the rubber stamp. Thus the average politician, as portrayed in the cartoons, is supposed to dress loudly (usually in checks), wear a gold watch chain, smoke black cigars, and be interested in the material things of life.

Now comes David H. Lane, republican city chairman of Philadelphia, who says: “In all my experience [Mr. Lane is 76 years old] I have never seen the politician that the newspaper cartoonist's picture. Take any thousand politicians, and you will find them an honester, straighter body of men than a thousand in any other profession.”

Unfortunately for the politician, his past associations with gang rule and bossism have identified him with those institutions. Cartoonists must make their figures recognizable without labels. The laboring man must have the biceps of a blacksmith, and must wear a box cap. Similarly the politician must smoke strong cigars and wear check suits. Otherwise, how would the public know him?

PREFER SENTIMENT TO HATRED

Picture postcards of the war, which probably reflect popular feeling fairly well, are not quite so merry as in the early days. A year ago caricatures of the kaiser were in great demand, but now the cards that sell best are of a sentimental or domestic type. The kaiser still appears in various characters—as a dachshund on crutches, a guy, a Zeppelin gasbag, a burglar, and, in company with the crown prince, as a bad pear— but such cards are no longer in conspicuous positions in shop windows. The kaiser, it seems, can no longer be relied on as the chief stock-in-trade of the picture postcard artist. The British public—always eager for change—is apparently losing interest in him.

The sentimental cards are growing in number daily. Pictures of the soldier saying good-bye, and of his return home, are in every window, and there is a great number of cards based on what may be called cinema emotion. A young soldier stands on guard outside a tent, and in the sky, among the clouds, apparently no more than 200 feet up, is the face of a girl. The soldier is charged with saying: “I wonder if you miss me sometimes.”

There are several pathetic series, chiefly concerned with good-byes. Probably they are not very true to life, but they sell very well—not among soldiers, but among elderly non-combatants. “Good-bye, mother darling,” says the soldier to his weeping mother. But do such farewells happen except on picture post cards?—London News and Leader.

THE BIZARRERIES OF ALBERT BLOCH

Albert Bloch, once cartoonist and caricaturist of Reedy's Mirror, of St. Louis, now of Munich, has 25 of his most recent paintings on exhibition at the City Art Museum of St. Louis. Among them is a portrait of Robert Minor, the cartoonist of the New York Call. Speaking of the paintings, Reedy's Mirror says: “They are to the Greeks foolishness. They are not after-impressionist, but before-impressionist and beyond. The exhibit is an escape from the conventional into a realm of almost, if not quite, pure art—wherein painting enters as does music.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

H. M. Waddell, a New York cartoonist, accompanied by his wife and children, has been making a trip from New York to San Francisco in a “house car.” An automobile equipped with all the comforts of home was used, and Mr. Waddell and his family traveled prairie-schooner style, camping by night wherever the setting sun found them.

BUSHNELL, DOC & CO.

E. A. Bushnell, recently cartoonist of the Central Press Association, of Cleveland, announces from New York that he has gone into business for himself. And, what is more, he has taken “Doc,” that melancholy hound of his, back into the firm. “Doc,” it will be remembered, was banished recently after having appeared in more than 3,000 cartoons.

O. O. McIntyre, who is a silent partner in the enterprise, and who was at one time associated with Bushnell in the west, writes the following appreciation of the cartoonist:

“Bushnell has a more serious mien now but beneath his shy, reserved exterior one feels instinctively that he is a confirmed optimist. He can laugh while going over the bumps better than any man I ever saw.

“One day our freckled-faced office boy was missing. We called him Rags and that described him. He drifted into our midst on the crest of an Ohio blizzard to keep warm and he became an office fixture as well as an office joy. No one teased Rags more than Bushnell. He would send him after wallpaper stretchers and once had the lad perspiring profusely when he sent him after a bucket of editorials and an unfeeling linotype operator filled his bucket with slabs of lead.

“No one knew where Rags had gone. Later we learned from others—not from Bushnell—that the lad had, from an accident on the street, become crippled. He was a Horatio Alger type in real life, for three were dependent upon him—a mother, father and sister. Bushnell after the first week went out on a still hunt for Rags. He found him in the most squalid shack on the river front.

“The next day Rags and his family were transported to a modest little farm house near the city and during the day a wagon backed up with loads of provisions. Rags today is a college graduate. They say he too admires Bushnell's cartoons.”

THE WOODWORTH EXHIBITION

An exhibition of war cartoons from the collection of Mr. Newell B. Woodworth, of Syracuse, N. Y., was held at the Syracuse Museum of Fine Arts from September 15 to October 15. Hundreds of cartoons were shown, representing the United States, England, France, Belgium, Holland, Germany, Austria, Italy, Spain, the Latin American countries, and the British colonies. A fine exhibit of Raemaekers' work, many originals by American cartoonists, and the latest war posters from England were the principal attractions.

CARTOONIST HANNY MARRIED

William Hanny, cartoonist of the St. Joseph (Mo.) News-Press, was married September 23 to Miss Alida Wycoff, daughter of Mrs. C. F. Wycoff, of Chillicothe. The wedding took place at the bride's home. Mr. and Mrs. Hanny will reside in St. Joseph.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Uncle Sam in a monocle is one of the queerest of spectacles. A French cartoonist so represents him. Of the three parts of gall, the Parisian artists have two at least and an interest in what remains.—Brooklyn Eagle.

In November 1913 the magazine began to offer a monthly round-up of news about cartoonists and cartooning, eventually titled "What The Cartoonist Are Doing." There are lots of interesting historical nuggets in these sections, and this Stripper's Guide feature will reprint one issue's worth each week.]

THE MODERN CARTOON

From the Portland Oregonian

When it is declared that there are nowadays no great cartoonists or illustrators, it ought to be recalled that the conditions controlling the art of newspaper caricature and pictorial lampooning are not what they were fifty, or twenty, or even ten years ago. Let us go back no farther than Thomas Nast, who was the most famous, and usually regarded as the greatest, of all American cartoonists. Mr. Nast's first and only notable work was with Harper's Weekly. During the Civil War, a tremendous episode in our history, he began his work. No one who has examined the usual political and personal caricatures of that day can fail to note their wretched and brutal character—miserable as art productions and savage in spirit and expression. Mr. Nast did much to make the profession of the caricaturist respectable. His talents as an artist were considerable, but his insight into affairs, his understanding of the motives of men, and his ability to give them pictorial form are the real secrets of his power.

There was no rival for Nast. He was alone in a field practically untilled. He rarely drew more than a single cartoon a week, and it is easy to see that he had ample time for the study of events and for the full play of his genius. To a great extent the weekly drawing of Nast was inspirational, for undoubtedly he was a man of temperament as well as a student of current history. He was not called upon for a daily offering, and he was therefore not oppressed by the exacting and remorseless grind of daily journalism.

When Nast left Harper's Weekly, after years of remarkable service to his employment and to the cause of truth and decency in public affairs, he made no impression through his contributions to the newspapers. His vogue was gone. He died a heartbroken man. It is an open question whether he might not have sustained his great reputation if he had remained with Harper's. In his latter days other caricaturists had come to the fore and Nast and Harper's no longer enjoyed a monopoly in that line.

Who looks nowadays to an American weekly for a cartoon? Originally the newspaper had no pictures or illustrations and did not have them for many years after they were a feature of the weeklies and monthlies. But with the discovery of a practicable process of newspaper illustration, and with its development through the adaptation of engraving and other methods to newspaper needs, the place of the weekly and the magazine was almost wholly taken by the newspapers, so far as illustration of current events is concerned. Yet it is true that in Great Britain the cartoon remains the peculiar possession of the weekly, and it is the same in Germany. There is a wide difference, however, in the German and British methods, for the Briton seeks to make of his cartoon an elaborate work of art, and the German confines himself to simple lines and memory impressions. The Englishman often uses models and excels as a draughtsman. The German burlesques his subject, and strives for humorous and grotesque effects. So does the American, though there is in this country a wide variety of style and treatment. There is no real American school, as there is a British and a German school. But there are thousands of American cartoonists giving the public their daily output, and making their appeal on every possible subject of human interest.

There is now no Thomas Nast of American journalism. Under our conditions it is doubtful if there could be. But there are a great many fine artists drawing good cartoons and excellent cartoonists making pictures that could by no stretch of the imagination be called sound art. No one, for example, would describe John T. Mc Cutcheon as a true artist, but who has not enjoyed his remarkable contributions to the pictorial literature of American life in all its prominent phases?

It would be easy to name others who are doing good work. On the whole, the average is very high, and certainly an irreparable loss would be suffered by journalism if the services of the cartoonist were to be dropped. The cartoon has come to be an effort to editorialize in a picture the current daily feature of the news or of public thought. The old cartoon—the Nast picture —was a complex affair, always with a central theme, but with many figures and contributing or incidental suggestions. Now it is different. The modern cartoon is a simple thing, with one idea. It requires no study to understand its meaning or to comprehend its scope. It can be absorbed at a glance. It may not be art, but it is something even better. It is the symbol of a truth.

KING'S UNCLE SAM AGAIN

A Rev. M.R. Todd, of Elvaston, Ill., writes to the Chicago Tribune complaining about Frank King's “insipid, unpatriotic, unmanly cartoons.” Mr. King, specimens of whose work are reproduced elsewhere in this magazine, has created a “new” Uncle Sam, flabby and corpulent and rich. Says the Tribune in reply to Mr. Todd:

“The cartoons of Mr. King are correct representations of Uncle Sam as he really is. They might possibly indicate a little more amiability and moral quality, both of which the spirit of this nation possesses. They could not possibly exaggerate the fact that our idealized Uncle Sam requires more tape to measure his waist than his chest.

“It is in a way immoral for this nation to continue to regard itself as typified by a gaunt, muscular, forgiving, but powerful figure, slow to wrath but dreadful in it; able, when aroused in just cause, to admonish and punish the lesser and brawling nations of the earth.

“That is the favorite Uncle Sam of the American imagination, and he is in truth a dreadful figure—but dreadful to the persons who believe and trust in him.

“The lovers of a defiant Uncle Sam are the persons who never think of themselves as sustaining a bullet wound in the abdomen. That bullet is to rip open some other abdomen, and they are to live in the gratification of a pleased dignity.

“The Rev. Mr. Todd's subscription does not expire for nearly a year. If he will continue that long we promise him that the cartoons of Uncle Sam will record any improvement made in the shape and disposition of Uncle Sam. We hope, knowing what new spirit is filling the American people, that by August, 1916, Uncle Sam will be not a bit less just and peaceable, but a terrific lot more able to make his righteous indignation effective.”

To which the Milwaukee Sentinel adds:

“Cartoonist King has invented an 'Uncle Sam,' new style; a figure of Falstaffian girth and obese unfitness for anything in the way of a physical encounter, to take the place of the lean, powerful and sinewy 'Sam' and ‘Jonathan' of the stock cartoon, slow to anger, but terrible as Achilles and fit to whip his weight in wildcats, when roused.

“Mr. Todd considers it 'unmanly and unpatriotic' to portray Uncle Sam as fat and helpless.

“But what about the fact, Mr. Todd? Would 'twere otherwise. The thing to do is to make it otherwise; and to impress it on this nation that it must be made otherwise, and that is the end and purpose of the offending cartoons. Mr. King is telling some hard truths in a galling and rather ribald but effective way.”

THE CASE OF THE CARTOONIST

From the Chicago Tribune

Cartoons in newspapers are reasonably faithful indices of the political thought of the nation. They are theoretically directed in their appeal toward the entire circulations of newspapers, and they are designed to influence thought quickly.

But newspaper cartoons point out more than favorite policies; they indicate more than the specific opinions of the groups which make up the nation; they offer a clew to more than passing squabbles over immigration and neutrality, over national defense and extra-national trade. By their manner, their technique, they go to the bedrock of our democracy.

The cartoonist touches subjects which everyone talks of. But he assumes nothing as to the intelligence of the person he addresses. Out of the far west comes a graphic treatment of the desolate situation of national defense. Mr. Wilson, labeled, is standing in a gymnasium. In his hands is a medicine ball, labeled “preparedness.” He is about to throw it to Uncle Sam, labeled, who is extending his two arms, labeled “army” and “navy,” respectively. In the gallery is Bryan, labeled. On the wall in the form of the rules of the gymnasium is the phrase, “An ounce of prevention,” etc. On the floor is a book which by its label concerns self-defense.

This is not the only cartoon of the kind. The country over these same intricate, explicit drawings go forth by the thousands every day. An English cartoonist would assume that the whiskers of Von Tirpitz would identify him. The American will label him, will label the kaiser, Wilson, Bryan, anyone, every detail. The practice is virtually universal, and it raises the query whether the cartoonist has the public wrong or right. If he has it right it is still in the nursery playing with blocks. The real power of the cartoon is that its symbolism does not require exposition. That is ignored.

One difficulty may be that this nation has few types. The cowboy is fast departing; the ward boss, and the Boston child, etc. The cartoonist is handicapped by his medium. There are few explicit symbols.

The labeling of the obvious may be justified by experience. If it is we must accept a disconcerting theory of American intelligence. It would be pleasanter to think that the lack was in the cartoonist. The obvious may appear mysterious to his timidity. Otherwise this is yet a nation of parishes in which even Mr. Wilson, Mr. Roosevelt, or Mr. Bryan cannot expect recognition unless they be labeled or announced.

MURPHY SEEKS PASTURES NEW

J. E. Murphy, for four years cartoonist of the Oregon Journal, of Portland, has left that position to become cartoonist of the The San Francisco Call and Post. The change was made October 1. Prior to his connection with the Oregonian Mr. Murphy was employed on Omaha and Spokane newspapers. He has recently issued a cartoon booklet entitled “Mr. Tourist in Portland and Oregon,” dedicated to the “See Portland First” idea, and devoted to the business and scenic advantages of the Rose City.

FRANK BOWERS RETIRES

Frank Bowers, one of the veterans of cartoondom, has given up his position on the Indianapolis Star, and gone back to his old home in Oregon to become a rancher. Mr. Bowers is a cousin of the late Homer Davenport.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Puck has added to its numerous attractions a weekly cartoon by W. Heath Robinson, the London artist, whose quaint and amusing drawings for the London Sketch have given him a world-wide reputation.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Robert Minor, cartoonist of the New York Call, was one of the speakers at the recent mass meeting in Elizabeth, N. J., for the organization of the Call Boosters’ Club. Mr. Minor illustrated his talk with a series of cartoons designed to promote the interests of socialism.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

James E. Maher has joined the staff of the Milford, (Conn.) Times as cartoonist.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Another lamentable change is noticed, still speaking of the Colonel. The cartoonists have taken to drawing him with those famous teeth concealed by a mustache.— Rome (N. Y.) Sentinel.

NAST'S GRANDDAUGHTER WED

Miss Muriel Nast Crawford, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. W. R. Crawford, of New Rochelle, New York, and granddaughter of the late Thomas Nast, was married September 16 to Donald E. Battey. The wedding took place in the new Crawford residence on Overlook Circle, Beechmont, New Rochelle. Miss Sallie Nast was one of the bride's attendants. Thomas Nast Crawford and Thomas Nast Hill were among the ushers. Mr. and Mrs. Battey will live in a colonial house in Beechmont recently built by the bridegroom for the bride.

“HANSI’S” CRUSADE RECALLED

The death on the firing line recently of Lieut. Baron von Forstner, who gained notoriety as the result of the Zabern incident, recalls “Hansi's" cartoon fight against Germany. It was the stabbing by von Forstner of a crippled shoemaker at Zabern, Alsace, that inspired the Alsatian cartoonist in his anti-German crusade. “Hansi,” it will be remembered, was sentenced by a German court to serve a year's imprisonment, but managed to escape into France, where he is now serving as a lieutenant in the army. The Zabern affair, which occurred in 1913, created much excitement throughout Germany.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Hy Mayer, of Puck, has been visiting the Pacific coast fairs. He has cartooned his experiences for the movies.

“BRINK” JOINS NEW YORK MAIL

Robert M. Brinkerhoff, magazine illustrator and cartoonist, has joined the staff of the New York Evening Mail, and has been drawing the editorial-page cartoons.

“Brink” went from the Cincinnati Post to New York to try his hand at free-lancing, and won recognition by his drawings for Collier's, St. Nicholas, and other magazines. Before coming to Cincinnati he had been on the art staff of the Cleveland Plain Dealer.

“Am trying hard,” he writes, “to get a human note in serious stuff.” Samples of his work reproduced in this issue of Cartoons Magazine will show to what extent he has succeeded.

|

| Brangwyn Poster Stamps |

BRANGWYN’S WAR POSTERS

The Avenue Press of London has issued a series of poster stamps designed by Frank Brangwyn, the British artist, whose work for the Panama-Pacific Exposition has increased his popularity in America. The stamps will be sold for the benefit of certain war charities.

ORR RENEWS CONTRACT

Carey C. Orr, cartoonist of the Nashville Tennessean, has signed a contract agreeing to remain with the Tennessean two years more. Several rival publishers, it is said, were negotiating for his services at the time, including the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

Mr. Orr was born in Ada, Ohio, 25 years ago. For the first 13 years of his life he lived on a farm, then went to Spokane, Wash., where he received his high-school education. After finishing school he took a position in his father's lumber plant. By playing professional baseball on a Canadian team he earned enough money for a course at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts. He joined the art staff of the Chicago Examiner in 1911, and from there went to the Tennessean. His first cartoon for that newspaper had President Wilson as its subject. He was married recently to Miss Cherry Maude Kindel. Mr. and Mrs. Orr live in a pretty bungalow in Belmont Heights. Mr. Orr's cartoons, especially on political subjects, are deservedly popular at Washington, where he is almost as well-known as in Nashville. He is a Mason, and a member of the Rotary Club.

BERRYMAN AS GOLFER

Clifford K. Berryman, cartoonist of the Washington Star, is learning to play golf. A few days ago, according to a writer on the Star, after he thought he was capable of swinging at a ball without breaking his own neck, he stepped out on the green of the Columbia Country Club, all dressed up, with eighteen new clubs and a dozen and a half of brand-new balls.

He swung his driver at a dandelion and nipped its head; then he neatly drove a cigarette butt about thirty feet in the air and seemed to have every chance of making a 200-yard drive from the tee.

He built a fine little sand pile, placed one of those fine new balls upon it and then grabbed his club for business. He had the correct back swing and his eye was on the ball, but when he swooped downward the club head was scarcely within eighteen inches of the ball.

Then he drew back again and made another attempt. He did considerably better, as the distance between club head and ball was reduced to a mere matter of six inches.

However, that did not satisfy him. He next delivered a terrific swipe at the ball, which toppled from its tee and rolled about a foot.

Cliff looked up in dismay. As his face became visible to the occupant of a bench near at hand a voice was heard to say:

“Why, Berryman, is that you? I thought it must be Dr. Grayson.”

The audience was President Wilson. He had gone quietly to the bench to sit down and await his turn to drive.

THE ABUSED POLITICIAN

Cartoonists are too apt to use the rubber stamp. Thus the average politician, as portrayed in the cartoons, is supposed to dress loudly (usually in checks), wear a gold watch chain, smoke black cigars, and be interested in the material things of life.

Now comes David H. Lane, republican city chairman of Philadelphia, who says: “In all my experience [Mr. Lane is 76 years old] I have never seen the politician that the newspaper cartoonist's picture. Take any thousand politicians, and you will find them an honester, straighter body of men than a thousand in any other profession.”

Unfortunately for the politician, his past associations with gang rule and bossism have identified him with those institutions. Cartoonists must make their figures recognizable without labels. The laboring man must have the biceps of a blacksmith, and must wear a box cap. Similarly the politician must smoke strong cigars and wear check suits. Otherwise, how would the public know him?

PREFER SENTIMENT TO HATRED

Picture postcards of the war, which probably reflect popular feeling fairly well, are not quite so merry as in the early days. A year ago caricatures of the kaiser were in great demand, but now the cards that sell best are of a sentimental or domestic type. The kaiser still appears in various characters—as a dachshund on crutches, a guy, a Zeppelin gasbag, a burglar, and, in company with the crown prince, as a bad pear— but such cards are no longer in conspicuous positions in shop windows. The kaiser, it seems, can no longer be relied on as the chief stock-in-trade of the picture postcard artist. The British public—always eager for change—is apparently losing interest in him.

The sentimental cards are growing in number daily. Pictures of the soldier saying good-bye, and of his return home, are in every window, and there is a great number of cards based on what may be called cinema emotion. A young soldier stands on guard outside a tent, and in the sky, among the clouds, apparently no more than 200 feet up, is the face of a girl. The soldier is charged with saying: “I wonder if you miss me sometimes.”

There are several pathetic series, chiefly concerned with good-byes. Probably they are not very true to life, but they sell very well—not among soldiers, but among elderly non-combatants. “Good-bye, mother darling,” says the soldier to his weeping mother. But do such farewells happen except on picture post cards?—London News and Leader.

|

| Albert Bloch, "Still Life" (1914) |

THE BIZARRERIES OF ALBERT BLOCH

Albert Bloch, once cartoonist and caricaturist of Reedy's Mirror, of St. Louis, now of Munich, has 25 of his most recent paintings on exhibition at the City Art Museum of St. Louis. Among them is a portrait of Robert Minor, the cartoonist of the New York Call. Speaking of the paintings, Reedy's Mirror says: “They are to the Greeks foolishness. They are not after-impressionist, but before-impressionist and beyond. The exhibit is an escape from the conventional into a realm of almost, if not quite, pure art—wherein painting enters as does music.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

H. M. Waddell, a New York cartoonist, accompanied by his wife and children, has been making a trip from New York to San Francisco in a “house car.” An automobile equipped with all the comforts of home was used, and Mr. Waddell and his family traveled prairie-schooner style, camping by night wherever the setting sun found them.

BUSHNELL, DOC & CO.

E. A. Bushnell, recently cartoonist of the Central Press Association, of Cleveland, announces from New York that he has gone into business for himself. And, what is more, he has taken “Doc,” that melancholy hound of his, back into the firm. “Doc,” it will be remembered, was banished recently after having appeared in more than 3,000 cartoons.

O. O. McIntyre, who is a silent partner in the enterprise, and who was at one time associated with Bushnell in the west, writes the following appreciation of the cartoonist:

“Bushnell has a more serious mien now but beneath his shy, reserved exterior one feels instinctively that he is a confirmed optimist. He can laugh while going over the bumps better than any man I ever saw.

“One day our freckled-faced office boy was missing. We called him Rags and that described him. He drifted into our midst on the crest of an Ohio blizzard to keep warm and he became an office fixture as well as an office joy. No one teased Rags more than Bushnell. He would send him after wallpaper stretchers and once had the lad perspiring profusely when he sent him after a bucket of editorials and an unfeeling linotype operator filled his bucket with slabs of lead.

“No one knew where Rags had gone. Later we learned from others—not from Bushnell—that the lad had, from an accident on the street, become crippled. He was a Horatio Alger type in real life, for three were dependent upon him—a mother, father and sister. Bushnell after the first week went out on a still hunt for Rags. He found him in the most squalid shack on the river front.

“The next day Rags and his family were transported to a modest little farm house near the city and during the day a wagon backed up with loads of provisions. Rags today is a college graduate. They say he too admires Bushnell's cartoons.”

THE WOODWORTH EXHIBITION

An exhibition of war cartoons from the collection of Mr. Newell B. Woodworth, of Syracuse, N. Y., was held at the Syracuse Museum of Fine Arts from September 15 to October 15. Hundreds of cartoons were shown, representing the United States, England, France, Belgium, Holland, Germany, Austria, Italy, Spain, the Latin American countries, and the British colonies. A fine exhibit of Raemaekers' work, many originals by American cartoonists, and the latest war posters from England were the principal attractions.

CARTOONIST HANNY MARRIED

William Hanny, cartoonist of the St. Joseph (Mo.) News-Press, was married September 23 to Miss Alida Wycoff, daughter of Mrs. C. F. Wycoff, of Chillicothe. The wedding took place at the bride's home. Mr. and Mrs. Hanny will reside in St. Joseph.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Uncle Sam in a monocle is one of the queerest of spectacles. A French cartoonist so represents him. Of the three parts of gall, the Parisian artists have two at least and an interest in what remains.—Brooklyn Eagle.

Labels: What The Cartoonists Are Doing

Comments:

The brief mention of the “Zabern Incident led me to look it up ... an interesting sequence of events in Germany right before the start of WW1.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zabern_Affair

Post a Comment

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zabern_Affair

Friday, February 07, 2020

Wish You Were Here, from Hans Horina

Here's another postcard in the Hans Horina series published by J.I. Austen Company of Chicago. This one is A-263.

Labels: Wish You Were Here

Comments:

"Bones a week" was recognized slang for weekly pay -- Googled and found a couple of dated instances mixed in with dozens of articles about how many bones you should allow your dog. A 1911 article held up twenty bones a week as an example of lousy remuneration for a bookkeeper, so guessing 4 bones a week places this card as much earlier.

I know I've seen "bones a week" in old fiction, but I don't think I've ever seen "bones" used for dollars in any other context.

Post a Comment

I know I've seen "bones a week" in old fiction, but I don't think I've ever seen "bones" used for dollars in any other context.

Thursday, February 06, 2020

Obscurity of the Day: Ain't It Just Like a Woman?

C.L. Sherman, one of the mainstays of the Boston Traveler's cartooning bullpen, wasn't the strongest delineator of the human form, so his comic strips tended to star animals. In Ain't It Just Like a Woman?, ducks are the animal of choice though they don't really figure much into the gags.

The foibles of women are a favorite subject of cartoonists, and Sherman found no shortage of gags to mine with this series, which ran in the Traveler and in syndication as one of his weekday strips from January 1 1909 to February 24 1910, a respectable run for those days.

In October 1909 Sherman had an attack of good grammar and changed the title to Isn't It Just Like a Woman? for the remainder of the series.

PS -- the byline on the second example to E.H. Weaver is a mistake; he was another cartoonist in the Traveler's bullpen, but he did not work on this series.

PPS -- can anyone explain the gag book title in the bottom example to me? I just can't make anything sensible out of "Lean Jawra Jibby".

Labels: Obscurities

Comments:

Hello Allan-

The "Lean Jawra Jibby" on the book is ham handed parody on the name of Laura Jean Libbey, (1862-1924)authoress of mushy but popular women's novels such as "A Dangerous Flirtation" and "A Forbidden Marriage", and later, an advice to the lovelorn column in the NY Mail called "Cupid's Red Cross."

I notice several of these examples have the credit line "State Pub Co." which indicate they are from the St.Louis Star, which for some reason, assumed the copyright on the Traveler material they ran, though, ironically, the miscredited Weaver one does have the original "B.T." identia.

The "Lean Jawra Jibby" on the book is ham handed parody on the name of Laura Jean Libbey, (1862-1924)authoress of mushy but popular women's novels such as "A Dangerous Flirtation" and "A Forbidden Marriage", and later, an advice to the lovelorn column in the NY Mail called "Cupid's Red Cross."

I notice several of these examples have the credit line "State Pub Co." which indicate they are from the St.Louis Star, which for some reason, assumed the copyright on the Traveler material they ran, though, ironically, the miscredited Weaver one does have the original "B.T." identia.

Wow, even if I had one of Libbey's novels on my nightstand I don't think I would have been able to connect those dots. Nice catch, Mark.

Although the ST Louis Star may have also used that name, State Publishing Co. was indeed the sometimes used name for the Traveler's syndication arm. I've seen that copyright appearing in the Traveler itself.

--Allan

Although the ST Louis Star may have also used that name, State Publishing Co. was indeed the sometimes used name for the Traveler's syndication arm. I've seen that copyright appearing in the Traveler itself.

--Allan

Hello Allan-

The Star's corporate name was "State Publishing Company" for years before the Traveller stuff, The earliest Daily Stars I've seen were after the Eksergian, et.al. material and the early WCP section. That would be in about September 1905, when they dropped a Sunday ish and took the weekday NEA syndicate for three years. Then they had the Traveller features for a year and the took Hearst dailies and a new sunday edition with a Hearst comic section. I go on about it here to establish there wasn't any chance of a Traveller newspaper chain. If you recall the traveller in those days, it was a very "respectable" paper, (i.e. BORING)

If the Traveller used it's "State Publishing" name, why would some series have the "B.T." designation?

The Star's corporate name was "State Publishing Company" for years before the Traveller stuff, The earliest Daily Stars I've seen were after the Eksergian, et.al. material and the early WCP section. That would be in about September 1905, when they dropped a Sunday ish and took the weekday NEA syndicate for three years. Then they had the Traveller features for a year and the took Hearst dailies and a new sunday edition with a Hearst comic section. I go on about it here to establish there wasn't any chance of a Traveller newspaper chain. If you recall the traveller in those days, it was a very "respectable" paper, (i.e. BORING)

If the Traveller used it's "State Publishing" name, why would some series have the "B.T." designation?

Hi mark --

This is an interesting question, but I'm not finding much anything to shed any further light.

I did some web searches and could find no citations of a State Publishing Company associated with either the St Louis Star or the Traveler, so that's a research dead end for now.

Is it your belief that the Boston paper was syndicating its material through the St. Louis Star, or are you working on some other hypothesis?

Best, Allan

This is an interesting question, but I'm not finding much anything to shed any further light.

I did some web searches and could find no citations of a State Publishing Company associated with either the St Louis Star or the Traveler, so that's a research dead end for now.

Is it your belief that the Boston paper was syndicating its material through the St. Louis Star, or are you working on some other hypothesis?

Best, Allan

No, actually it's a damfino. The Star felt a need to replace the actual copyright line, obviously that being the "B.T." designation. The Star took the Traveller stuff for one year, July 1908 to June 1909. Before that, the NEA material never had any identia to mess with, and were left alone. When they took Hearst features , they couldn't touch the copyrights. Why they would do that to the Trav's toons I can only guess, it may be some obscure law where they had to recopyright them, or maybe they had exclusive Missouri rights to them, and needed to do it that way.

I've found strange anomalies in the handling of copyrights like that. Some papers inferred that their strips were of their own doing... Gasoline Alley was "Drawn for the Spokesman-Review by King" (though the C.T.'s imprint would remain), or a strange subjective one,like the Janesville (Wisc.) Gazette had across the title border of Bringing Up Father for about ten years in bold letters where a subtitle might go, a 1920 copyright. And a real pain in the neck, papers like The Philadelphia Inquirer, years after their syndicate ended, and Hearst's evening Milwaukee paper, The Wisconsin News, ERASED all copyrights. why would that be done? That always nabbed my nanny.

Post a Comment

I've found strange anomalies in the handling of copyrights like that. Some papers inferred that their strips were of their own doing... Gasoline Alley was "Drawn for the Spokesman-Review by King" (though the C.T.'s imprint would remain), or a strange subjective one,like the Janesville (Wisc.) Gazette had across the title border of Bringing Up Father for about ten years in bold letters where a subtitle might go, a 1920 copyright. And a real pain in the neck, papers like The Philadelphia Inquirer, years after their syndicate ended, and Hearst's evening Milwaukee paper, The Wisconsin News, ERASED all copyrights. why would that be done? That always nabbed my nanny.

Wednesday, February 05, 2020

Obscurity of the Day: Say, Genevieve

In addition to possibly creating the wonderful Militant Mary, Elizabeth Kirkman Fitzhugh did a little work at the New York Tribune in the mid 1910s. Most of that work was done for the Sunday children's page, and included two series. The first, Say, Genevieve, concerns a pair of little girls who dream big before having second thoughts. This delightful strip, with poetry that actually bounces along quite stylishly (a rarity among newspaper strips in verse), ran on the page from April 26 1914 to April 4 1915. It didn't run every week, though; Fitzhugh's regular spot at the top of the page offered non-series strips about half the time.

Early strips were signed with her maiden name, Elizabeth Kirkman. Alex Jay has determined that she married Valentine Fitzhugh in January 1914, so either she was producing these strips well in advance, or took awhile to decide if she was going to sign with her married name.

Say, Genevieve was dropped in favor of a new series concocted by Fitzhugh, The Antic Family's Alphabet, but that series was cut off in mid-alphabet when she left the Tribune.

Labels: Obscurities

Tuesday, February 04, 2020

Obscurity of the Day: All the Comforts of Home

Through most of the 1900s and 'teens Gene Carr was with the Pulitzer organization, dividing his time between higher profile Sunday strips like Lady Bountiful, Phyllis and Step-Brothers, and his occasional weekday strips that ran in the Evening World, like All the Comforts of Home.

All the Comforts of Home offered readers the opposing viewpoints of bachelors and married men. In Carr's strip the bachelors are having a great time but pining for home, wife and babies, while the married man, though playing up his contentment to the boys, actually deals with ill-behaved children, absent wives and constant home maintenance projects.

The weekday strip had two runs in the Evening World, first from January 25 to October 5 1905, then the strip was revived from July 5 1907 to July 11 1908. The second series shortened the title to Home Sweet Home until June 1 1908, but it ran so rarely that the count of strips in the last month and a half of the run is actually greater than the whole prior year.

The 1907-08 series strips were resold to the Chicago Tribune, which added color and ran them in the Sunday section.

Labels: Obscurities

Monday, February 03, 2020

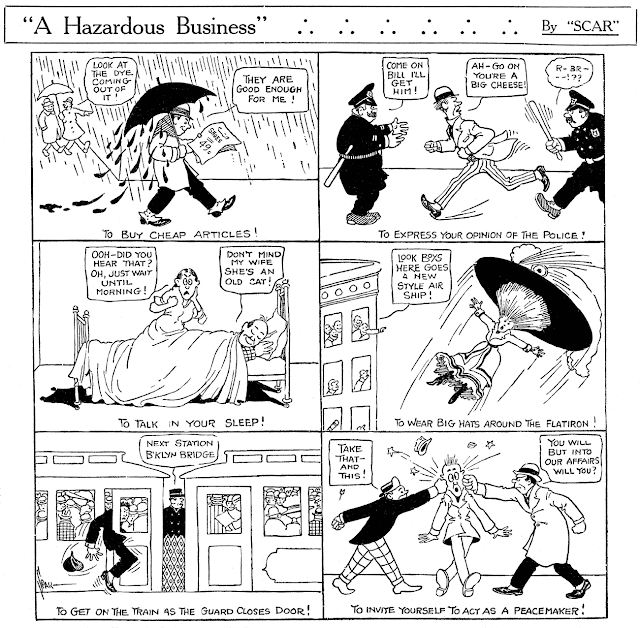

Obscurity of the Day: A Hazardous Business

A.W. "Scar" Scarborough, who did stints at many of the major New York City evening papers -- the Evening World, the Evening Telegram and the Evening Globe at least,was a perfectly fine cartoonist but couldn't seem to make anything stick for more than a few months or so at any of those papers. He also did sports cartoons on occasion, and I'm assuming that the rest of the time he settled for other work in the art departments of those papers.

Today's obscurity, A Hazardous Business, is one of the three series he placed with the Evening World in his stint there, which seems to have been at least 1908 to 1910. It's rather unusual in that the feature gives every impression of having been intended as a panel cartoon, but the World instead ran the panels in groups of six. That wasn't a bad decision because the cartoons don't have much punch, but grouped together the reader at least feels like they're getting quite a lot of gags for their trouble.

A Hazardous Business appeared in the Evening World from December 5 1908 to January 11 1909.

Labels: Obscurities