Saturday, November 18, 2023

One Shot Wonders: One Thing That Sticks in Danny Long's Noodle by Will Sperry

Way back in 2012 Cole Johnson sent me this strip that he clipped out of the San Francisco Bulletin of January 20 1912. He wondered if this was a one-shot cartoon or part of a series starring this Danny Long fellow.

I never looked into the matter until recently, but then I noticed that the Bulletin is now available at newspapers.com. Well, as it turns out, Danny Long isn't a cartoon character at all, but rather the manager of the San Francisco Seals. Thus the gag makes perfect sense, and additional review of the paper reveals that Will Sperry was their sports cartoonist, apparently just in 1911-12 based on a quick perusal.

Sperry's early cartoons for the Bulletin are nothing to write home about, but by 1912 he had quickly developed into a pretty darn fine cartoonist as evidenced by our sample. What happened to Mr. Sperry, then? Well, I'm no expert at tracking but I found a few tidbits. Seems he went to Europe when World War I broke out and served valorously in relief of Belgium, being cited for bravery on several occasions. When the U.S entered the war, he took a commission with the expeditionary force. When the war ended he elected not to come back to the States but rather to live in France. After that I lose track of him. I wonder if he got back into art over there in Europe once his war hero days were over?

Labels: One-Shot Wonders

Friday, November 17, 2023

Obscurity of the Day: Nobody Works Like Father

Here's a series by the ever-busy pen of Gene Carr that reminds us that "social media" is not a phenemenon limited to the current century by any means. Long before the internet, long before TV, even long before radio, people could still tune into cultural zeitgeists. Yes, fads and memes were with us in 1906 -- maybe they didn't travel at the speed of fiber optics, but they still worked their way through our society at an amazing speed.

In 1905 a new song was published called "Everybody Works But Father", a comic ditty about a lazy father. A number of artists recorded it, and here's one of them:

It was a big hit and soon spawned postcards and other trinkets bearing the title. Soon there were also reply songs, like "Father's Got a Job", and various singers offered new and alternative lyrics. In the world of comics, Gene Carr took up the gauntlet and decided to defend poor father. His series Nobody Works Like Father debuted on January 28 1906*, offering new song lyrics featuring a father who slaves for his family only to be treated like dirt.

Carr must have really relished creating this series because the strips are in my opinion some of his best work; funny, on point, animated, and smart. Coulton Waugh, on the other hand, singled it out in The Comics for what may or may not be a diss, "too reminiscent of the ancient days of Dickens and Cruickshank to last long in a modern world."

As with social media today, though, the world quickly tired of its memes even way back when. Gene Carr's Nobody Works Like Father ran its course in less than a year, last appearing November 25 1906*.

* Source: St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

Labels: Obscurities

Wednesday, November 15, 2023

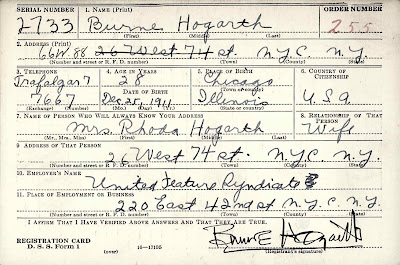

Ink-Slinger Profiles by Alex Jay: Burne Hogarth

…Max kept those sketches and took them and his young son to the Art Institute of Chicago in 1924. Burne was accepted as a student at age 12. By age 15, he was an assistant cartoonist at Associated Editors’ Syndicate. He flourished at the Institute and the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts….Burne graduated high school at the dawn of the Great Depression….

Comics Scene: Give us a capsule history of your career and early background. You graduated from the Chicago Art Institute?Burne Hogarth: No, I didn’t, as a matter of fact, I went to the Institute but it was only a kind of supplemental activity while I was really in the process of going to high school and at the same time doing art work.I went to the Art Institute, started Saturday classes, at the age of 12 [1924]. My father thought that I had sufficient material to be able to enroll in classes like that and so he took down a bundle of stuff one day, on a Saturday, and said “Let’s go see what they will think about this.” And they accepted me—so that’s how my training began. Later I went to the Institute taking special courses, but I didn’t enroll in any formal classes. I couldn’t because we were not an affluent family and [the world] was headed into what was later to be known as the Great Depression.CS: When did you know you had a talent for cartooning?BH: Very early, when I was a kid, about four. My father would sit and design furniture and cabinets—he was a carpenter and cabinet maker—and I would ask for my own piece of paper and pencil. And when I would say, “What should I draw?” he would push a cartoon under my nose and say “Here, draw this.” So the cartoon became a kind of focus of attention.CS: What happened after you left the Art Institute?BH: I enrolled in the Academy of Fine Arts in Chicago. There I studied further drawing and then cartooning as another side of that. That’s when I met a cartoonist who was working for a syndicate and other people who were working for newspapers, and we used to get heavily into what syndication was all about…deadlines and magazines and doing samples and taking them around. I did gags and editorial cartoons, illustrations and that was all part of my portfolio.I used to take this around and get some jobs in magazines and at the same time worked at odd jobs like driving a truck, selling newspapers and shoes—nothing was too high, too low, or too intermediate to do, because there was obviously an economic necessity.One of the people I met at the Academy introduced me to one of the syndicates. I worked (for them) in his studio and I was his assistant. I was just an apprentice. I used to come in and sweep up. I learned lettering and I learned also there’s something about the craft of doing work on deadlines. And more than anything else I learned how to use pen, brush, different media and all sorts of things in a very professional way. Maybe two and a half, three years later I sold my first feature to Bonnet Brown.

Ivy Hemmanhaw. It was one panel, humorous gags about Americana. I was just 18 [1930]. It lasted about a year and then I went on to teach in the Emergency Educational Program, which came along about the time I was 20–21 [1932–1933], and I went to school, too. I went to Northwestern University, the University of Chicago, and studied psychology, anatomy, sectional anatomy, and then things altered. The Depression got worse and under the urging of friends who had relocated to New York, I made my foray into the field in New York, into the syndicate field, very quickly—and that became the start of a whole new and different part of my life.

…Well, I want to tell you, I started work in February. It was agonizing. I spent 11 hours every day, half the time in the library, and I’d be sitting up nights and working incessantly, and by the end of the week I’d be drained. I’d send this stuff off to the syndicate…I lived the life of a monk in that period….” In the fall, the syndicate decided to end the strip. Hogarth said, “…‘Thank God this thing is over! I’m through with it’. The pirate strip was the heaviest chore I ever carried. And I was glad it as over.

Classes are still forming at the Cartoonists and Illustrators School, 112 W. 89th St., it was announced by Silas H. Rhodes, director. Nationally prominent cartoonists and illustrators, headed by Burne Hogarth, illustrator of “Tarzan,” comprise the faculty and lecturing staff.

…When I got to meet Bernie Hogarth, I went up to his studio, which was in his apartment. My brother [Dan Barry] had an apartment like that later on.You would go into the main area of the apartment and it was one step down into the living room area, but there was also a staircase at the end of the living room that went upstairs to the bedrooms, in an apartment house, believe it or not. I don’t know how they designed this thing, but it was really remarkable. So you’d go up the staircase and there’d be a landing there and that landing would take you into the bedrooms. Then in one of the upstairs bedrooms was his studio. It was this beautiful, brightly lit studio and it was on Central Park West.It was a beautiful apartment and of course he was very wealthy. He’d written anatomy books and he taught and of course they paid him very handsomely on the Tarzan daily. Trust me, he was very well paid, especially for those Sunday strips. He was a brilliant guy….

…By the mid-1950s she had met artist Burne Hogarth, famous as the man who drew the Tarzan comic strip. They soon married and had two children….…In 1962, the Hogarths moved from their Queens apartment in search of more space for the boys and a studio for Burne. In Mount Pleasant [New York], they found a fortress of a house, resembling something out of Charles Addams….…Her personal life has also become a testing ground. She and Burne were divorced last year….

...In 1953 she married cartoonist Burne Hogarth, who drew the Tarzan comic strip (1937–50) and founded the art school that became New York’s School for the Visual Arts. Soon after son Richard was born in 1956 and son Ross in 1959, the Hogarths moved to suburban Westchester County, which had a reputation for good public schools. (She and Burne divorced in 1981, and nine years ago she married Art Kamell, a longtime activist and former labor lawyer.)

Labels: Ink-Slinger Profiles

Monday, November 13, 2023

Obscurity of the Day: Miracle Jones

After his masterful performance on Tarzan, it's amazing to think that Burne Hogarth followed it up by not just one but two total misfires. The first was Drago, an atmospheric quasi-western set in South America that showcased fabulous art but herky-jerky storytelling.

Hogarth's second attempt at getting back in the newspaper limelight is today's obscurity, Miracle Jones. An ill-advised departure from the action/adventure milieu, which was Hogarth's specialty, this strip tries to adapt Hogarth's dynamic art style to a humor strip. Miracle Jones was a bald-faced copy of James Thurber's Walter Mitty character, a nebbish whose fantasies are played out for the amusement of readers. The character had just been adapted into a 1947 blockbuster movie starring Danny Kaye, so Hogarth just jumped on the bandwagon with a character who is Walter Mitty in every respect excpt the name.

United Feature originally offered the strip under the title J.P. Miracle, but changed it prior to release. The strip began on February 15 1948* in a vanishingly small list of papers as a Sunday-only feature**. Hogarth provided impressive art but it was all for naught. United and Hogarth threw in the towel before even the first year anniversary, the strip apparently ending on December 5 1948***.

Art expert Alberto Becattini offers us an interesting aside on Miracle Jones, stating that future E.C. Comics star Bernie Krigstein ghost-pencilled two weeks worth of the strip. There may have been other assistants and ghosts involved, too, because I notice that Hogarth does not generally sign his name in the final panel, only in the often dropped title panel. Was he trying to tell us something? Considering that he was back working on Tarzan at this time it seems likely that other hands helped out on this throwaway strip.

* Source: Boston Post

** A few sources claim the strip began in 1947, but no evidence for this has been found.

*** Source: Jeffrey Lindenblatt based on Long Island Press.

Labels: Obscurities

So the idea (implied) that it took Hogarth ghosts to get both strips out makes perfect sense.

Can anyone expand?

Sunday, November 12, 2023

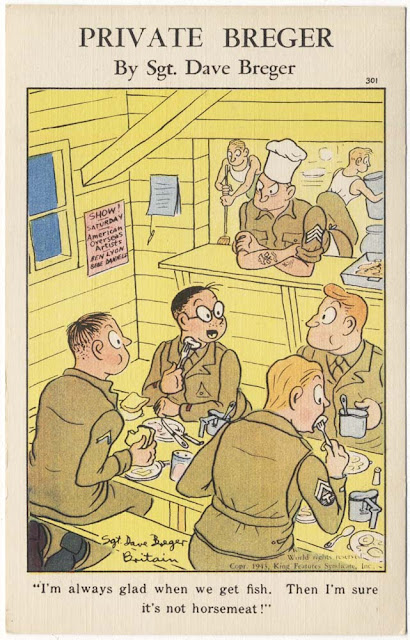

Wish You Were Here, from Dave Breger

Here's another Private Breger postcard issued by Graycraft. This one is number 301, which I suppose would give it pride of place as the first in the series, unless there's a #300 lurking out there somewhere. The original cartoon ran in papers in 1943, and we're reasonably certain the card series was issued in 1944.

Labels: Wish You Were Here