Saturday, May 27, 2017

Herriman Saturday

February 11 1909 -- Japan is stimulating the building of a large shipping fleet by offering subsidies. Although the reason is ostensibly to stimulate trade with the rest of the world, the LA Examiner sees the war-making possibilities of a large fleet.

Labels: Herriman's LA Examiner Cartoons

Friday, May 26, 2017

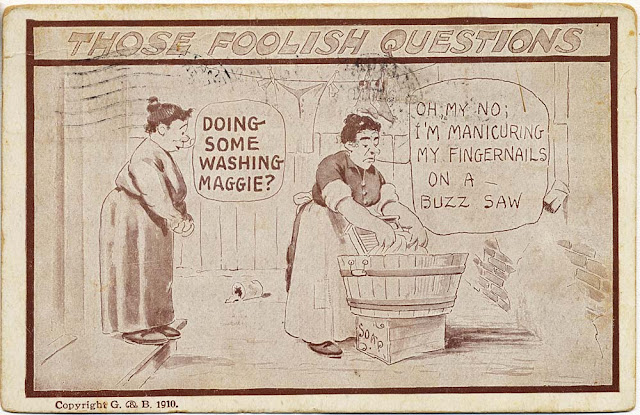

Wish You Were Here, from an Anonymous Rube Goldberg Copyist

Rube Goldberg's foolish question cartoons were so popular in the late-1900s and early 1910s that a company called G & B decided to issue a series of cards on the subject. Not wanting to pay Mr. Goldberg for the privilege, though, they seem to have commissioned an anonymous cartoonist to duplicate his style. The cartoonist sometimes managed to ape Goldberg convincingly, but this particular card doesn't look much like Goldberg's work to me. The acidic rejoinders were just about as good as Goldberg was coming up with, which makes me wonder if they just stole his lines. That's evidently not the case with this one, though, as I just ran Goldberg's real washerwoman gag a few weeks ago on Wish You Were Here.

Labels: Wish You Were Here

Thursday, May 25, 2017

King News by Moses Koenigsberg: Chapter 3 Part 2

King News by Moses Koenigsberg

Published by F.A. Stokes Company, 1941Chapter 3

The Deadline that Led to a Crusade (conclusion)

link to previous installment link to next installmentThe publicity scrimmage in San Antonio made no impression on the Times staff. The indignation of the cub reporter was ignored. At best, the professional dicta of a tyro were presumptuous. And this verdict was affirmed in a few days in clamorous accents. The boy journalist’s presumption had led him through an exciting adventure in civic reform to the brink of personal disaster.

The inception of the crusade might have been traced to Sadie Ray’s exotic complexion. Few subjects yielded a farther-flung harvest of gossip. East of San Pedro Creek, Sadie wasn’t mentioned by name. “That creature” was ample identification in the whispered councils of a sorority, the muted chatter of an afternoon tea or the intimacy of cozy-corner talks. It was the fashion to consider her halfway between a myth and a taboo. But that was impossible when Sadie went shopping. Ordinarily, her bountiful patronage was dispensed at “The Mansion,” in the heart of a precinct in which prudery reached the nadir of uselessness. There she reigned in rococo splendor. At scheduled hours, tradesmen, artisans and personal servitors offered their wares and services to “the queen of the demimonde,” a title Sadie arrogated with more or less diffidence and very little dispute. Nevertheless, despite the contrary pressure of her retinue and advisers, it pleased her once or twice a year to promenade through the marts of trade. Each of these occasions kept the tongues of urticated virtue wagging until the next visitation. It was as if Sadie had toted the whole primrose path into the centers of primness.

|

| 1/1/1890, Sadie Ray the licensed madam |

Her visits were made afoot. Choice of the pedestrian role rested in a somewhat confidential understanding with the police. She descended from her unique equipage at the edge of the red-light district. There, the prancing pair of Arabian horses, the darkey driver in gorgeous livery topped with a red, white and green cockade, and the natty brougham trimmed in tan and maroon, remained the cynosure of gaping admirers while the flamboyantly overdressed mistress minced her way through the shopping section.

Sadie’s public appearances were always in state. A step behind her strutted a colored maid in a severely simple gray uniform. In the wench’s right hand, carried as if it were a floral bouquet, showed a crystal vial encrusted with jewels. To the uninitiated, this coruscating object might have been the symbol of an occult rite. But Sadie was averse to mystery. She dismissed all doubt with opportune calls for her smelling salts. Beside the maid swaggered a Negro footman in a regalia that matched the outre costume of the coachman waiting “across the creek.” He, too, bore an emblem of courtly service—his mistress’ gold-mesh purse.

It was a diverting show. Perhaps a paucity of humor accounted for the fact that vexation greatly exceeded the amusement it produced. But there were other reasons for puritanic impatience among San Antonio’s bourgeoisie. They ran through the texture of civic hypocrisy that the budding crusader sought to unmask. They linked his campaign with his first view of the peach-bloom enamel on Sadie Ray’s piquant face.

The encounter spilled a mess of sociologic riddles. Phil Shardein, chief of police, had just halted Sadie with her garish retinue in her carriage of many colors. Why had the chief of police stopped Sadie Ray? There had been an argument. What was it about? Sadie terminated the conversation with the gesture of a sultana dismissing an ambassador.

“It’s nothing your paper will print,” Shardein growled, “but, of course, you nosey reporters have to know everything. Well, I’ll tell you. I just gave Sadie hail Columbia for crossing the deadline.”

An impulsive question clamped a curb on the police chief’s inclination to talk. “What and where is the deadline?” he repeated in unconcealed disgust. “Oh! That’s a little joke we use to keep the girls under control.” And the novice knew his faux pas would entail a search elsewhere for the facts. It had been a silly blunder. Why had he forgotten the one commandment that appeared in the codes of two worlds—the axiom observed alike by the hunter and the hunted, the cop and the crook—“Never wise a sucker.”

There was a deadline. But its devious course led through labyrinthian zones no map revealed. It had the covert sanction of smug committees and boards of social purity leagues. Invested with that pious authority it had grown into an institution that none paused to question. Sadie Ray’s chromatic parade was permitted as far east as South Flores Street. There she might drive alongside the back wall of San Fernando Cathedral. But the deadline barred her from the front of the edifice. It was not the theory that the church might be more susceptible on one side than another to the effluvia of Sadie’s proximity. Ostensibly, the rule was devised to shield arriving or departing communicants from the carnal distractions of her perambulating show. Actually, it set a mark for the valuation of special liberties. Privileges and favors were created for sale or barter. Spurious licenses of personal freedom were extended or restricted by the wave of a hand.

The boy journalist probed the system under which such patronage became possible. It seemed to him a mockery of law and justice. No ordinance or statute delegated to any official the power to institute or regulate such a practice. There was convincing evidence that sordid profits accrued to those in control. There was no testimony of any benefit to the public. Of course, there was the age-old claim of moral advantage—that virtue was conserved and fostered by such regulations as kept in the background the realities of vice. But there was also the contrary view that a false curtain of concealment served as the most effective provocateur of prurience.

A court proceeding resolved these speculations into definite action. Warrants were issued for 340 men and women on charges of disorderly conduct. Apparently, the judicial machinery of San Antonio had been geared to mass operation. But the occasion was not novel. It was a regular round-up. The defendants were fairly well divided between the two sexes. The men were professional gamblers. The women followed an older if no more honorable occupation. Each had been a resident of the city for the three months preceding their arrest. Their arraignment was attributable as much to the calendar as to the nature of their respective offenses. Four times a year, they were hauled into court and run through a grist mill in which pleas of guilty and sentences rolled out as if from an automatic contrivance.

Three months before, this routine had offered no special significance to the cub. But now the name of Sadie Ray flared up from the docket. She had been assessed the same penalty imposed on each of the other women—$25 and costs. Surely, “the queen of the demimonde” deserved a different rating. Why were identical punishments meted out to all the culprits? Were there no degrees of culpability? Or was this proceeding something aside from the processes of justice? Was it part of the sinister skein from which the apocryphal deadline was drawn?

The first bolt of publicity was loosed that afternoon. The story was recounted as straight news. No editorial conclusions were essayed. They would have been joyously excised by the city editor.

The second story was purely statistical. It showed that the public coffers had received $8,500 from 340 fines of $25 each, while the court costs of $90 per case amounted to $30,600. The innocent statement was included that the latter sum was absorbed in the regular fees legally allowed to the various public officials who shared in the initiation, recording and prosecution of the proceedings.

Then came the blast. It was the third and last instalment of the series. The county clerk was quoted in confirmation of the fiscal data. On the basis of the last quarterly round-up of the underworld, the average annual contribution to the public treasury was $34,000. This was compared with the yearly yield of $122,400 in fees to officials. These officers received no salaries. In lieu of fixed remuneration, they collected the charges prescribed by law for each form of official service they could devise. At this point, comment was necessary to expose the viciousness inherent in the custom. Conclusions offered by the reporter would be eliminated. But a statement from an outsider would be news. The crusader presented an interview with an anonymous sociologist.

“By this procedure,” ran the statement, “our prosecuting officials are set up in a partnership with crime. They are forced to look for their compensation in the profits of those whose incomes are derived from violations of the law. So, it works out that the emoluments of office are dependent in large measure on the continued operations of harlots and gamblers. Small wonder that we note a supervisory attitude—a sort of paternalism—toward these law-breakers. Every bawd and every gamester saved from premature incarceration will be one more contributor on the scheduled ‘pay-off’ days. We cannot deny that this usage puts upon our citizenship an onerous responsibility that should be gravely considered.”

A list of the fee officers followed. It evoked an outburst of indignation from every man named. Their protests resounded throughout the county courthouse. They had been branded as the beneficiaries of prostitutes. They had been “held up to the ridicule, contempt and abuse of the community.” That was an ominous phrase. It appeared in the Texas statute defining criminal libel.

A conference of the political inner circles was called. Republicans as well as Democrats attended. This was a situation that involved both parties. The attack had not been aimed at a partisan group. If it were followed through, it might affect the whole county set-up. What was Sam Maverick trying to do with his newspaper? Somebody was throwing rocks. If it wasn’t Sam it was his crew of Northern newcomers. And if he couldn’t or didn’t prevent them from starting this backfire maybe he couldn’t or wouldn’t prevent them from continuing it. The district attorney—a Republican—had a plan to take the load off Sam’s shoulders. At the same time a wholesome lesson could be given Maverick for the future. The grand jury happened to be in session. There was no question that indictments for criminal libel could be slapped on the pestiferous busybodies that were trying to snarl up the orderly processes of honest government in Bexar County.

The district attorney’s plan was adopted. The next day, three true bills of indictment for criminal libel were returned against W. A. Stinchcomb, managing editor, Charles Merritt Barnes, city editor, and M. Koenigsberg, reporter. It was a crushing surprise to the beardless crusader. He received the news with more bewilderment than dismay. Stinchcomb drew him aside.

It was the managing editor’s cue to feign an indignation he didn’t feel. The cub was his find—his protege. “I don’t want to lay it on too thick,” he said, with a hint of apology in his voice, “but I must point out that you’ve gotten us all into a jam. I won’t even discuss the blame. I merely notify you of your immediate dismissal. A lawyer may explain to you why I have to take this step. I will say that I think you have the fault of over-zealousness.”

And so ended my first newspaper crusade. But the fight was not abandoned. The evils of the fee system of compensation for prosecuting officials had been publicized. Reformers in San Antonio and elsewhere took up the attack. And, over the years, the lone crusader grew to realize that the loss of his job on the Times had not been a sacrifice in vain.

It was a grievously perplexed boy that turned from Stinchcomb’s desk for a dolorous trudge to the sheriff’s office. There, Chief Deputy Druse handed him a blank bail bond for $500. “Get the first two men you meet to sign this and bring it back,” he said with a friendly smile. There was something reassuring about this. Obviously, Druse didn’t share Stinchcomb’s feeling of gravity. He didn’t even care who the bondsmen might be. But the jobless journalist decided on caution in this respect. He sought out two friends of the Koenigsberg family. On their loyalty he felt he could rely. Yet his selection led to a quaint crisis.

It followed his decision to abandon San Antonio to its fate. He would transfer his journalistic ardor to larger fields. His resolution was hastened by several developments. He detected a lack of hospitality in the local newspaper offices. Either a simulated or a genuine misunderstanding prevailed concerning his ill-fated crusade. Sharp criticism came from various quarters. What had this young upstart attempted? Did he think “the powers that be” would stampede over a silly newspaper item? Did he think he’d get anywhere throwing pebbles at pyramids? An editorial commentator tagged him “a misguided gossoon.” That was the last straw. It turned the scale for immediate departure. Other cities would appreciate the public service that true journalism could confer.

But the libel indictment might pop up to hamper freedom of movement. A conference with counsel was necessary. Colonel Shook, the boy’s revered mentor, volunteered to serve without fee. The venerable lawyer predicted that the case would never be called for trial. “I’m quite sure these indictments were not intended as part of any punitive program,” he elucidated. “It’s the first time I’ve known it to be done in the South, but in your case grand-jury proceedings have been employed to quash a newspaper campaign. Writs of injunction were unobtainable. But this process is more advantageous to its sponsors than such writs would have been, even if valid. It averts the expenses of a civil suit and you will observe that it achieves the desired effect of complete suspension of the acts complained about. The chief value of these indictments to the complainants lies in their pendency. Once they are brought to trial, this value ceases.

"Of course, all this is most irregular. It involves vicious conspiracies, corruption of court processes and various other crimes. But who is going to the trouble and expense of ferreting out the culprits and establishing the proofs of their offenses? Certainly you re not in position to do so at this time. Obviously, what you want most is an opportunity to find a job. Go where you please. Even if they make the pretense of pushing the case for determination, I’ll arrange for abundant time for your return to face them. I don’t think that occasion will arise.

“You ask what Stinchcomb meant when he said a lawyer might explain his reason for dismissing you. That action would fortify his defense in the event he went to trial. It put him in better position to disavow responsibility for anything you had done.”

This was a Godspeed. The great arenas of metropolitan journalism beckoned. But the unattached journalist reckoned without his sire. A determined effort was afoot to prevent the boy’s departure from San Antonio. Disclosure of the facts followed an urgent summons from one of his bondsmen. L. M. Michael, a neighborhood patriarch, was in a quandary. He had readily signed the bail bond with G. B. Frank, a merchant in the next block. “Both of us assumed your father would approve our action,” he began. “Instead, he was very much displeased with us.”

“You probably know,” Mr. Michael continued, “that your father was grief-stricken when you became an active newspaperman by accepting a job on the Times. This morning he bewailed to me that a son of his might pass through jail to the companionship of gutter drunkards.

“I do not want to influence your course. It is necessary for me, however, to acquaint you with facts that you must consider before it is too late. Your father is absolutely determined to prevent your leaving the city at this time. He believes your departure now would mean your irrevocable commitment to a newspaper career. Also, he insists it is your duty to remain here until your indictment is disposed of. He will not exercise parental authority to restrain you because he is convinced that would only fortify your obstinacy and make more certain your ultimate disregard of his wishes.

“I wonder if you realize how strong a character your father is and how inflexible can be his determination. Perhaps you’ll form a better judgment after a brief review of his young manhood. I daresay I know more of the details than you do. Neither of your parents is loquacious. Your mother’s father was a Polish patriot. His regular occupation was the breeding and trading of horses. This vocation lent itself to the assembling of mounts for armed troops. There were many uprisings against Russia in those days.

“Your grandfather was of considerable service to the insurgents. Once he was overtaken with a group of companions attempting to ford the Vistula River. He had an extraordinarily powerful physique. A Cossack grabbed his horse’s bridle. He slapped the soldier out of his saddle. The Cossack drowned. Your grandfather was sentenced to Siberia. Friends were able to obtain his release. He returned home to live out an oath he had taken on the steppes of Siberia. He vowed that no daughter of his would become the wife or the mother of a conscript of the Czar.

“So, no suitor was acceptable who would not agree that on their wedding night he and his bride would leave Russian jurisdiction forever. Your father cheerfully assumed this pledge. Several days before the time set for the nuptials, he was notified to present himself for military service. His failure made him a fugitive. While soldiers were seeking him, he was sheltered by kinsmen at whose home the wedding was finally performed in great secrecy. Meanwhile, your mother’s father put together a large chest into which pillows and cushions were fitted. In this box, artfully hidden under a load of hay, your parents spent their wedding night on the road that led out of the Czar’s domain.

“All went well until the frontier was reached. There a squad of dismounted Cossacks became suspicious. They ordered the driver to halt. But he was prepared for this contingency with some reversible barbs in the harness. A tug on a strap suddenly turned the sharp points into the horses’ flanks. The animals reared and plunged and the soldiers scurried away from the seemingly unmanageable animals. The driver lashed the team into a gallop and not until then did the Cossacks detect the trick. Firing at the wagon as they ran for their horses, they mounted for pursuit. But the fugitives had crossed the border before their pursuers could get under way. So, your parents left their native land under a hail of bullets.

“How they made their way to England, how they lived several years in London and Liverpool, how they came to America after the close of the Civil War, how they moved westward with protracted stays in Cincinnati and Memphis and how they reached New Orleans, your birthplace, you probably know in detail. But what you have probably never pondered sufficiently is the resoluteness and tenacity that carried your father with the responsibilities of his growing family through all the trials and hardships of this exploration of a strange country. Do you realize what it meant when at New Orleans he applied for and secured the contract to serve as sutler to a battalion of General McKenzie’s army on its march through Indian Territory and western Texas?

“He knew that he would accompany troops traveling through regions filled with savage Indians. Remember this is a man who had never held a gun in his hand. How he ever got the courage to take his family on that expedition, I have never understood. But he did; and the unyielding firmness he showed should be in your mind when you analyze his present disposition.

“All this merely leads up to why I sent for you. Your father has fully resolved that the safety of a prison cell would be better for you than the pitfalls of the life of what he calls ‘a tramp reporter.’ For that reason, he has pleaded with both Mr. Frank and myself to vacate your bond so that the sheriff may take you into custody. Mr. Frank has finally consented on condition that I do the same. I have declined your father’s request. But he has great perseverance. Nevertheless, I’m satisfied he would give up his plan if its execution passed even for a moment beyond the friendly hands of Sheriff Campbell. I shall quote a threadbare maxim: ‘A word to the wise is sufficient.’ ”

Mr. Michael was in an irksome impasse. He could reject but he could not repress the importunities of the distressed father. He could warn but he could not direct the contumacious son. But his warning was effective. It made clear to the boy that the danger of detention lay only in Sheriff Campbell’s bailiwick. That danger must be instantly averted. Daybreak must find the journalist outside Bexar County. There was no time for even the scantiest preparations. The matter of funds was a disturbing problem. Cash resources on hand totaled just 65 cents. But this was a plain case of skedaddle in which belonged no thought of comfort or preference.

Anyhow, older newspapermen had on occasion overcome the difficulties of traveling without money. There were several methods. One which had always sounded the simplest was to find unobserved lodgment on a freight train. That was the mode of transportation selected for the flight from San Antonio.

There had been a preparatory course for the night’s adventure. During his apprenticeship on the Times, the boy had picked his favorite companions among itinerant typesetters. “Tramp printers” they called themselves. In no other circle did he find so rich or so ready a fund of current information. These men absorbed and assorted in facile memories all the thoughts and facts that passed through their fingers into type—speeches by famous orators, reprints of carefully culled articles on the progress of the arts and the sciences, digests of government reports, census returns, statistics of all kinds, the papers of statesmen of the old and the new worlds, editorial essays on all these topics and the wealth of curious data assembled by the exchange editors of that generation. The nature of their craft was in itself a college of general learning. The curriculum was as catholic as the range of printed intelligence. There were no outmoded masters under whom to stagnate. An unquenchable wanderlust forced upon them a variety of mental stimulation as wide as their wanderings. The newspaper apprentice had used the procession of these vagrant philosophers as a self-replenishing staff of preceptors for his university of empiric knowledge. Now, he was to turn to practical account their lectures on the lore of the nomad.

A “through” freight offered many advantages. It reduced to a minimum the probability of contacts with prowling watchmen. It curtailed the opportunities for extortion by callous trainmen. At midnight, the young dabbler in vagabondage was stumbling over tracks in the Southern Pacific freight-yards. His tutelage under veterans had proved of no avail. He couldn’t find a through train to board. He was at the door of desperation when a section hand stopped him. The railroad man was painfully devoid of gentleness. His words and gestures betokened an excessive dissatisfaction over the boy’s presence. A swiftly approaching locomotive interrupted the scuffle. A parley ensued. It transformed the bellicose railroader into a friendly guide. A munificent honorarium of fifteen cents hastened the transformation.

Daylight found the errant journalist asleep on the catwalk of a cattle car rumbling eastward from San Antonio. He was not burdened with impediments. A package containing a change of linen lay inside the folds of a light fall overcoat on which his face was pillowed. And so, with a criminal indictment hanging over him, with the professional rating of a discharged reporter and the economic status of a hobo, he set out on a pilgrimage to journalistic crusades. He had attained the eighth month of his fourteenth year.

The immeasurable boldness of precocious youth!

Chapter 4 Part 1 next week link to previous installment link to next installment

Labels: King News

Wednesday, May 24, 2017

Ink-Slinger Profiles by Alex Jay: Virginia Krausmann

Virginia A. Krausmann was born in Cleveland, Ohio, on August 29, 1912. Krausmann’s birthplace was found on her marriage certificate, and birth date in the Social Security Death Index.

The 1920 U.S. Federal Census recorded Krausmann as the only child of Albert and Florentine. They lived in Cleveland ay 8805 Platter Avenue.

The Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 24, 1928, reported that Krausmann took first place in the annual county oratorial contest. The Plain Dealer, September 29, 1929, said Krausmann was elected vice-president of the Inter-club Council at the Girl Reserve conference.

In the 1930 census, Krausmanns resided in Rocky River, Ohio, at 19431 Frazier Drive.

Krausmann was a senior when she received a fifth-year scholarship from the Cleveland School of Art, as reported in the Plain Dealer, May 23, 1934.

Seattle Daily times 10/20/1935

The 1940 census said Krausmann lived her parents in Rocky River at 19431 Frazier Drive. She did not work in 1939.

Krausmann married Kenneth Eugene Gordon on February 1, 1941, according to their marriage certificate at the Cuyahoga County, Ohio, Marriage Records and Indexes at Ancestry.com. The 1940 census said Gordon was newspaper staff artist. The event was mentioned in the Plain Dealer, February 2, 1941:

Miss Virginia Krausmann, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Adelbert J. Krausmann, 19431 Frazier Drive, Rocky River, and Mr. Kenneth E. Gordon of Fry Avenue, Lakewood, were married yesterday afternoon at the Krausmann residence. Rev. Edwin McNeill Poteat performed the ceremony at 4. The couple will reside in Kenilworth Avenue, Lakewood. The bride was graduated from the Cleveland School of Art.Krausmann passed away May 15, 1986, in Bay Village, Ohio, as recorded on her death certificate. Her husband passed away May 22, 2005.

—Alex Jay

Labels: Ink-Slinger Profiles

Tuesday, May 23, 2017

Ink-Slinger Profiles by Alex Jay: Robert Wathen

Robert Griffin Wathen was born in Madisonville, Kentucky, on October 14, 1910, according to the 1942 Monthly Supplement to Who’s Who in America. Wathen’s parents were George Francis and Nell Griffin.

In the 1920 census, Wathen was the second of three brothers. Their father was a merchant in a notion store. The Wathens lived in Madisonville at 248 Broadway.

The Monthly Supplement said Wathen graduated from Louisville Male High School in 1927. He attended the Louisville School of Art from 1926 to 1927. In 1928 Wathen was in the art school of the Louisville Conservatory of Music where he studied with Bethuel Moore (1929 to 1931) and Paul Plaschke (1932 to 1934).

A 1928 Louisville, Kentucky city directory listed Wathen as an artist at 1023 South 1st. The 1929 and 1930 directories said Wathen was employed in the engraving department of the Courier-Journal and Louisville Times. His address was 1023 South Brook.

That address, according to the 1930 census, was the Wathen family residence. Wathen’s occupation was newspaper cartoonist. Wathen continued to live with his parents through mid-1932.

The Monthly Supplement said Wathen married Helen Eugenia Page in June 1932.

The 1933 Louisville directory listing said Wathen was an advertising artist at the Courier-Journal and Louisville Times. He and his wife lived at 202 Linden Lane.

Over the next few years their address was 205 North Birchwood Avenue in Louisville.

The Monthly Supplement said Wathen was creative designer and artist with the Courier-Journal Job Printing & Lithographing Company from 1933 to 1939.

American Newspaper Comics (2012) said Wathen drew the strip Bela Lanan, Court Reporter, aka You Be the Judge, starting July 6, 1936. It was written by L. Allen Heine. The strip was handled by the Carlile Crutcher Syndicate and ran into Fall 1942.

According to the Monthly Supplement, Wathen was an instructor at the Louisville Art Academy in 1935. He served as art director at the M. R. Kopmeyer Advertising Agency beginning in 1939.

1940 census recorded two sons and two daughters for artist Wathen and his wife. They made their home in St. Matthews, Kentucky, at 513 Cornell Place.

Louisville directories, from 1949 to 1960, said commercial artist Wathen maintained a studio at 633 South 5th in room 200.

Wathen passed away December 5, 1988, in Louisville, according to the Social Security Death Index. He was laid to rest in Resthaven Memorial Cemetery.

Labels: Ink-Slinger Profiles

Monday, May 22, 2017

Will the Real Bela Lanan Please Stand Up?

[Allan's note: Carlos Altgelt is a researcher currently working on an index of the long-running Argentine comic book Patoruzito. When trying to track down some comic strips he found in early issues, which he thought might be from the U.S., our paths crossed. I was able to ID one of the strips as Bela Lanan Court Reporter, but Mr. Altgelt was very curious about the background of the strip. I couldn't help much as I am woefully uninformed about the genesis and creators of this intriguing but quite obscure comic strip.

Mr. Altgelt was so fascinated with this unusual strip that he went on a mission to uncover its history. Amazingly, he was able to dredge up an impressively complete picture of the strip, its creators, and the story of its creation and end.

I feel greatly honored that Carlos Altgelt has written up the story of Bela Lanan and consented to having it appear here on the Stripper's Guide blog. Now, finally I'll shut up and let you learn the fascinating tale. Take it away, Carlos ...]

Will the Real Bela Lanan Please Stand Up?

by Carlos A. Altgelt / caltgelt@gmail.com

Patoruzito, the Argentine weekly magazine of the 1940s, 50s and 60s, marked an era in the history of comic books in that Latin American country. With 32 large format pages (9” x 11½”), it debuted on October 11, 1945. At the outset, it carried 25 different strips, of which the large majority (15) were of U.S. origin. What made it such an important addition to the vast number of comic books circulating in Argentina in those days, was that in time, its editor, Dante Quinterno, paved the way for local artists such as José Luis Salinas of Cisco Kid fame, Bruno Premiani and Alberto Breccia to appear in its pages. By 1952, only four foreign strips remained. The U.S. strips present in that first issue included such icons as Captain Marvel Jr., Flash Gordon, Buck Rogers and the lesser known Miki and You Be the Judge. And it is this last one which brought me to write the following article.What happens is that when Toni Torres, owner of “El Club del Cómic” store in Buenos Aires asked me to write the index of Patoruzito, I knew I was in trouble because, at Toni’s suggestion, I had just published a book listing all the comic books edited by the legendary scriptwriter Héctor Germán Oesterheld (El Eternauta, Mort Cinder, Ernie Pike, Sherlock Time). There were over 400 issues, and I detailed each one of the strips that appeared in each number, the artists and writers, and its origins if foreign, including a color photograph of the covers. But while Oesterheld’s magazines carried an average of 5 strips per issue, Patoruzito boasted four to five times that amount and it ran for 892 issues!

|

| From Patoruzito #1 |

The challenge was made, however, and I accepted it by first attacking the seemingly impossible to find origin of a strip titled Júzguelo usted. Impossible, that is, until Frank Motler put me in touch with Allan Holtz’s Strippers Guide. He was able to identify the strip as Bela Lanan, Court Reporter.

|

| Original US versions of the Bela Lanan story above - note the differing panel order |

Bela Lana, Court Reporter (a.k.a. You Be The Judge) was an American newspaper daily comic strip which ran from the mid-1930s to the early 1940s. It was written by Leopold Allen Heine, drawn by Robert Wathen and syndicated by Carlile Crutcher of Louisville, Kentucky.

In an era dominated by adventure, humorous and family life strips, Bela Lanan was one of the few non-fiction entries, along with strips like Rex Collier’s War On Crime and James Carroll Mansfield’s Highlights of History.

Practically forgotten today, what made it unique was its “hook.” Every week it presented a court case in six episodes where the reader, acting as judge and jury, was challenged to deduce the outcome. At the end of each weekly installment, the actual verdict appeared in a text column on a separate page.

The cases were based on actual legal suits, not only from the United States but from around the world. The characters’ names were changed, however, to protect the innocent so to speak. If one was interested, all one had to do was to send a self-addressed stamped envelope to the editor to find the true details of the litigation.

The strip was easily recognizable among the six or seven that appeared on each page in those golden days because the first panel, with a height 2½ times its width, always carried, not a drawing, but the title of the episode. This was preceded by the words “The Strange Case of…” (sometimes “odd” or “tragic” were used instead of “strange”). At the bottom of this first panel, the reader was reminded that the story was in six episodes and, below it, the number of the daily installment. With few exceptions, the title of the strip itself was shown at top left with the name of its writer as “L. Allen Heine” on the right.

The story of its inception is just as interesting as any of the cases themselves. It all began when Carlile Crutcher, recently graduated from Centre College in 1926, became the secretary and personal assistant to powerful judge Robert Worth Bingham, politician, diplomat and newspaper publisher of the progressive Louisville Courier-Journal. As a publisher, the judge championed women's suffrage, the League of Nations and labor unions. Soon Crutcher learned the ins and outs of the law as well as the publishing trade.

He developed an interest in copyright law and approached Harry Robertson, editor of the paper, with the idea of publishing a daily short column highlighting, in no more than 20 lines and headed by a single picture panel, the odd proposals granted by the United States Patent and Trademark Office. Robertson accepted the concept and Freak Patents debuted on Monday, April 22, 1935, at the bottom of page 2 of the Courier-Journal. The texts were written by Crutcher, with line drawings by Thomas Harvey Peake, a local freelance writer and artist. It was copyrighted under the name Carlile Crutcher.

|

| First Freak Patents, 4/22/35 |

|

| Last Freak Patents, 8/8/36 |

The feature was readily accepted by the public, but soon Crutcher began toying with another idea based on real life. While searching for the odd patents, he came across a 62 year-old resident of Louisville, Lawrence S. Leopold and, through him, also met Leopold Allen Heine.

According to Stephen J. Monchak, in an article titled “How A Hobby Became a Feature Is Told” (Editor & Publisher magazine, March 30, 1940):

"[Heine] had in his possession a trunk full of manuscripts dealing with unusual law cases. The manuscripts were written in longhand by the late William Lanahan, a former Louisville reporter who became an itinerant newspaperman. Lanahan not only worked on newspapers in this country but abroad. He made a hobby of collecting tricky court cases. When he died he willed his possessions, including the manuscripts, to Mr. Heine. [He] began briefing the Lanahan manuscripts so the cases could be condensed into a six-day picture serial. (…) In order to get fresh material, Mr. Heine reads law cases continually and each 100 cases usually nets one suit that lends itself to dramatization.”

Enthused with this wealth of information, Crutcher convinced Heine to become the writer of a new daily comic strip, You Be The Judge. Robert Wathen, a local watercolor artist, was to be the illustrator. His son, Joe Wathen, said in a comment on this blog that his dad “found characters to draw into the strip by visiting bars in downtown Louisville” (August 5, 2009). Neither Wathen nor Heine had any experience in the comic strip field nor would they have any additional ones in the future. That, however, didn’t deter Crutcher from marketing it. To that extent, still employed by the Courier-Journal, he ambitiously launched the Carlile Crutcher Newspaper Feature Syndicate, nominally a news service but mostly dedicated to the distribution of the new comic strip, which made its first appearance on July 6, 1936. Its first installment was titled “The Burning of the Golden Gate,” not referring to the famous San Francisco Bay bridge, but to the sinking of a steamship of that name bound for Panama. The Wilkes-Barre (PA) Record was one of the few newspapers that carried it that day. Freak Patents continued for another month but on August 8 was published for the last time.

|

| Week 1 of You Be The Judge, 7/6 - 7/11/1936 |

|

| Week 1 court decision |

Shortly after launching You Be The Judge, a Chicago radio station complained that they were using that title in one of their shows. Rather than argue, Crutcher asked the newspapers that carried the strip to change its title to Bela Lanan, Court Reporter and used this name to solicit further subscriptions.

In the 12th weekly episode, the one starting on September 21 1936, Heine gives a slightly veiled tribute to his mentor, William Lanahan. In the story he explains the reason behind the odd new name for the strip by narrating the story of Bela Lanan (recall that no real names were used in the strip). He tells us that Lanan/Lanahan was born in Budapest in 1881. That should explain the origin of the name ‘Bela’ since it was and still is a very common given name in Hungary, and perhaps was William Lanahan's real given name, anglicized when he came to the US. At any rate, ‘Lanan’ is not an anagram as many thought, but a shortening of the Magyar traveling reporter’s family name.

|

| Bela Lanan's biography in You Be The Judge, 9/21 - 9/26/1936 |

Bela Lanan’s comic strip biography begins with Heine’s affectionate show of gratitude to his friend. He considers it a duty to tell his story, which was a source of inspiration for his writings. As told in the third episode, Lanan left Hungary at the age of 20 because, after being accused five years earlier of stealing a purse, he was a marked man. He tells his mother: “The courtroom has cast its spell upon me. The judge, the jury, the fiery prosecution, the heroic attempt of the defense. I can never be a great lawyer. My voice is weak, but I will be a great reporter. But never in Budapest! My friends, my arrest, they will not forget. I am going away!”

And so he does. He spends five years roaming “the rolling hills of Scotland, the lonely moors of England, the African veldt and the Australian bush” collecting all sorts of bizarre legal suits which were to appear decades later in the strip. We find him then in Bombay, India, where he has just reported an important case and he is told by the British Mercantile Office to go to Buenos Aires. The year is 1905 and, while the strip doesn’t mention it, it probably had to do with the Argentine revolution of that year.

He continues tramping the world, always looking for the odd judicial case. In 1916 he is in Verdun during the First World War. A piece of shrapnel hits his eye and his optic nerve receives a severe shock. He is blinded for life. He then emigrates to the United States, where he dies in California in the early 1930s.

In the words of Heine, he was “a man of strange make-up, odd, eccentric, a world traveler and—before he died—a recluse, alone and almost forgotten.” But he is quick to add that “he had the courage of his own convictions. He knew his weakness and he knew his strength—even at the early age of 20—and that’s something that many of us would like to be able to say. (…) His records are all that remain and they will unfold, from week to week, the strange and interesting, but sometimes tragic, revelations that came to this man of mystery. As Bela Lanan traveled, he collected these true stories, and saved evidence to prove that even the most unusual in his collection are true.”

The week after this dramatic introduction to the public, on October 5 1936, Crutcher applied for a trademark which was properly granted on April 13 the following year. By the end of 1936, six months after its debut, Bela Lanan was carried by 40 domestic newspapers.

Three years later, Crutcher changed his mind regarding the name of the strip and advised his local and overseas subscribers to use the name You Be The Judge again. The Wilkes-Barre Record reverted to the original name on April 24, 1939.

Then in May of 1942 Crutcher entered the United States Army Air Force and, in his own words, “thereafter found it impossible to manage the sale and distribution” of the strip. According to a 1956 legal transcript, the last distribution was furnished to domestic subscribers on September 4, 1942 (a questionable date since this is a Friday, and such dates are normally given as Mondays or Saturdays). Crutcher apparently never used the name or produced the strip beyond that time. In all 322 weekly stories would have appeared in the United States by that time. According to Crutcher, by that time only five domestic subscribers were carrying the strip and he didn’t publicly identify which ones they were. That makes it difficult to know the last time Bela Lanan, Court Reporter was published in the U.S. However, on the basis of the episodes that appeared abroad, specifically the Argentine magazine Patoruzito, which carried strips that most probably never appeared in the U.S., I estimate that the total number would have been 337, enough material to last until December 19 1942. I have been able to document the first 295 stories in U.S. newspapers (last appearance on March 1 1942 in the Longview (TX) News-Journal).

By the end of its run, 71 domestic newspapers—among them the Wilkes-Barre Record, Brooklyn Eagle, Abilene (TX) Reporter-News and Longview (TX) Daily News—and 21 abroad (one being the Lethbridge Herald of Alberta, Canada), had purchased the feature. Curiously, the Louisville Courier-Journal, professional home of Carlile Crutcher, never carried the strip.

Once World War II ended, Crutcher was released from the Air Force in January 1946. He soon found out that because of shortages of newsprint, newspaper publishers were a tough market for selling new strips.

|

| Samples of the Saturday Evening Post version of You Be The Judge, 1951-52 |

In 1948, the Curtis Publishing Company began, in its weekly magazine The Saturday Evening Post, a one panel drawing titled You Be the Judge with a short statement of facts inviting the readers to solve the case. This brought in 1950 a lawsuit by Crutcher for infringement of his trademark. He lost the case because in the opinion of the court, “the plaintiff has failed to establish a right to the exclusive use of the name. (…) ‘You be the judge’ is an expression in common use, containing no element of novelty or fancy, and is by no means unique. For a name which is merely descriptive to have the protection of the law, it must be established that the name has acquired a secondary meaning identifying it with the goods.” An ideal case for a Bela Lanan series!

Carlile Crutcher was born in Jefferson Kentucky on November 9, 1906 and died on April 19, 1966 in Louisville.

Sources: Crutcher’s obituary from the Louisville Courier Journal (April 20, 1966, page 40); newspaper accounts and strips of that era; Allan Holtz’s online Stripper’s Guide articles; Argentine Patoruzito comic book (1945-1950); Lawrence S. Leopold family information from the1940 US Census; Crutcher v. Curtis Publishing Company legal suit (January 11, 1956); Trademark application #353,497 (October 5, 1936).

Personal notes: I wish to express my gratitude to Mr. Allan Holtz for his help in finding the original source of “Júzguelo usted” and his encouragement to write the preceding article.

I have compiled an Excel spreadsheet listing all the story titles for Bela Lanan, their running dates, and the newspaper sources in which I found them. Researchers wishing to get a copy of this list are invited to email me at caltgelt@gmail.com