Saturday, November 10, 2018

Herriman Saturday

October 15 1909 -- Another Baron Mooch strip that is in my 'to be published' pile, so I guess it was missed in Bill Blackbeard's book. My copy of the book is inaccessible right now, so if anyone has a copy, I'd love to hear whether this one appears or not.

Labels: Herriman's LA Examiner Cartoons

Comments:

Hello, Allan! You've got another "exclusive," chum--the book excludes the strips for both 10/15 and 10/16!

Post a Comment

Friday, November 09, 2018

Wish You Were Here, from Charles Lederer

Here's a Charles Lederer card, published in 1906 by the Monarch Book Company of Chicago.

Labels: Wish You Were Here

Thursday, November 08, 2018

Ink-Slinger Profiles by Alex Jay: Bearden

Romare Howard Bearden was born on September 2, 1912, in Charlotte, North Carolina. His birthdate is from the Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, Birth Index, at Ancestry.com, and the Social Security Death Index. When Bearden was drafted in World War II his birth year was recorded as 1912. Some publications and web sites have the birth year as 1911. His Social Security application had his birthplace. Bearden’s parents were Richard Howard Bearden and Bessye Johnson Banks.

Bearden’s father signed his World War I draft card on September 30, 1918. His address was 173 West 140th Street in Manhattan, New York City. He was employed as a buffet porter and steward on the Canadian Pacific Railway. A second, undated draft card had the address 231 West 131st Street in Manhattan and his job as dining car waiter with the Atlantic Coast Line rail company.

Bearden and his parents have not yet been found in the 1920 U.S. Federal Census.

The 1925 New York state census said the family were Manhattan residents at 173 West 140th Street. Bearden’s father was an inspector. The household included a maid who was a seamstress.

In the 1930 census, the Beardens and three lodgers resided at 154 West 131 Street in Manhattan. Bearden’s father was a health department inspector and mother a newspaper writer.

New York Age, February 27, 1932, reported Bearden’s college publication role.

Romare Howard Bearden son of Howard and Mrs. Bessye Bearden of 154 West 131st street, New York City, has been elected art editor of the Beanpot, humor magazine of Boston University where young Bearden is a student in the sophomore class. In his freshman year young Bearden was pitcher on the baseball team.

American Newspaper Comics (2012) said Bearden drew Dusty Dixon, in March 1933, for the Stanton Feature Service. No newspaper has yet been found that ran more than the two strips shown above, though printing dates vary widely.

In Art in Crisis: W.E.B. Du Bois and the Struggle for African American Identity and Memory (2007), Amy Helene Kirschke wrote

[Bearden] spent his first two years in college at New York University, graduating with a bachelor of science in education in 1935. He started drawing cartoons in college and became the art editor of the New York University student magazine Medley and the school newspaper's principal cartoonist. Bearden was part of a relatively new and small group of black cartoonists that was forging new territory in illustration. The work of E. Simms Campbell (who he met in Boston), Ollie Harrington, Miguel Covarrubias, Honore Daumier, Jean-Louis Forain, and Kathe Kollwitz would greatly influence him. His early cartoons, along with those he did for the magazine College Humor, established Bearden’s lifelong interest in social realism and social commentary through art. He also contributed cartoons to the nationally circulated Baltimore Afro-American, the urban League’s Opportunity magazine, and Collier’s. His early published comic strips included Dobby Hicks (which has been compared to the strip Henry), which was followed by Dusty Dixon, a more evolved strip. He felt neither strip was the ideal place for his social commentary and sought a better way to communicate his view of the black condition. His developing interest in identity, in his southern heritage, and in the issues of the people of the black diaspora, which became a dominant theme of his work, found their early expressions in his political cartoons of The Crisis. These political cartoons led him to pursue a career as a politically engaged artist.The strip Dobby Hicks mentioned above has not yet been found in any newspaper.

The Negro Star (Wichita, Kansas), December 1, 1933, published this item, “Mr. Romeo [sic] Bearden has designed a new Christmas Seal for the NAACP. He is a young artist and cartoonist of New York.”

In the New York Amsterdam News, March 19, 1988, Mel Tapley wrote

…Romare flirted with songwriting and might even have been a major league pitcher, having been on Boston University’s varsity baseball team, before he transferred to NYU. He’d even hurled a couple of summers for the Boston Tigers, an all-Black team. Twenty of his songs were recorded, among them “Seabreeze,” that featured Billy Exkstine and Oscar Pettiford….

…[In the 1930s Bearden] enrolled at the Art Students League, having soon decided that he preferred life of an artist to teaching math. George Grosz was his instructor and introduced him to the work of Kathy Kollwitz and Honore Daumier—all recorders of social protest….The Detroit Tribune (Michigan), July 9, 1938, said Bearden was a pallbearer at the funeral of James W. Johnson.

According to the 1940 census the Beardens lived at 50 Morningside Avenue. Bearden and his mother were deputy inspectors with the health department. His father was a public works inspector.

During World War II Bearden enlisted on May 7, 1942 in New York City. Tapley said “…Bearden, who during World War II was in the Army and became a sergeant, 372nd Infantry Regiment, studies in Paris under the G.I. Bill. The 372nd, [John A.] Williams pointed out, was an outfit that won hundreds of medals fighting with the French army.”

According to the Detroit Tribune, June 13, 1942, Bearden had a full-page illustration in the June Fortune Magazine.

Washington—(ANP)—Another striking blow at discrimination against Negroes in war industries, the Army and the Navy, was delivered by an organ of big business this week when Fortune magazine attacked such racial restrictions in a 10 page article in its June issue.Bearden’s mother passed away September 23, 1943. Her death was reported two days later in New York Age. At the time Bearden was a sergeant in the Army. His father was a Board of Health inspector who resided at 351 West 114th Street.

Entitled “The Negros War,” the article, which strikes out boldly against discrimination, is graphically illustrated with drawings by Charles “Spinuky [sic]” Alston. A full page frontispiece showing unemployed Negro workers standing near a defense plant was drawn by Romare Bearden….

New York Age, February 5, 1944, reported Bearden’s upcoming exhibition.

Miss Carrese Crosby, former publisher of books and magazines in Europe, is sponsoring an exclusive exhibition of the works of Sgt. Romare H. Beardcn, of the 372nd Headquarters Company, in the G Place Gallery, Washington, D. C. from Tuesday to February 15th. The artist-soldier left Saturday accompanied by bis father, R. Howard Bearden, to attend the preview on Sunday.A new art center in Harlem was reported in the New York Age, February 17, 1951.

Harlem’s newest cultural center, the LETCHER Art Center located at 2368 Seventh Ave., has brought together some of the country’s leading artists. Aside from Ohio-born Evelyn LETCHER, whose husband, Henry M. directs the three art centers established in D.C. by this talented duo, the center has recruited the services of Charles S. CARTER, Marc K. HEINE and Vivian S. KEYES, instructors to commercial art, ceramics and arts and crafts, respectively. The board of consultants reads like a “Who’s Who” in the world of art, with Elton FOX, Jacob LAWRENCE, Grayson WALKER, Romare H. BEARDEN aad Charles “Spinky” ALSTON making up the brilliant panel.The New York, New York, Marriage License Index, at Ancestry.com, recorded the issuance of a marriage license to Bearden and Nanette Rohan in 1954.

In the Amsterdam News Tapley said

…In the late Sixties, however, Bearden, [Norman] Lewis and [Ernest] Crichlow started the Cinque Gallery, which is still operating.The Museum of Modern Art exhibition “Romare Bearden: The Prevalence of Ritual” was from March 25 to July 9, 1971. The following year “The Prevalence of Ritual.” was at the Studio Museum in Harlem. The Amsterdam News, July 22, 1972, covered the exhibition and said Bearden’s

Cinque in Black history was a slave who ld a mutiny aboard a slaveship, piloted it to freedom, but then stood trial for the revolt.

…The initial goals for Cinque Gallery were: to provide a showcase for promising artists; share the collective experience of the founders with the newcomers; and to assist these discoveries in “getting their hands in.”

first one-man show was in 1940 at the studio of Ad Bates in Harlem. He was founder of the Spiral Artist Group, an organization formed primarily to deal with the problems of Black artists in America. He was also one of the founders of the CINQUE Gallery in New York.

He was appointed art director of the Harlem Cultural Council in 1964, a position he still holds. In 1969, he co-authored with Carl Holty in a book titled “The Painter’s Mind” and in 1970 was awarded a Guggenheim fellowship to write a history of Afro-American art. Bearden has shown in many group exhibitions and had in numerable gallery and museum shows in he U.S. and Europe over the last thirty years.

The 1964 collages, called “Projections,” marked a major breakthrough in his art. Since then Bearden has been working exclusively in collages.

Bearden passed away March 12, 1988 in New York City. The New York Times, March 13, 1988, said Bearden suffered a stroke at New York Hospital.

Further Reading

National Gallery of Art

Wikipedia

—Alex Jay

Further Reading

National Gallery of Art

Wikipedia

—Alex Jay

Labels: Ink-Slinger Profiles

Wednesday, November 07, 2018

Ink-Slinger Profiles by Alex Jay: Frank L. Stanton Jr.

Frank Lebby Stanton Jr. was born on May 5, 1895, in Atlanta, Georgia according to his World War I draft card which also had his full name.

In the 1900 U.S. Federal Census Stanton was the second of three children born to Frank, an editor and poet, and Leona. The family were residents of Atlanta at 422 Gordon Street.

The 1910 census recorded the Stantons at 300 Lee Street in Atlanta. Stanton’s father was the editor of a daily newspaper and his mother an advertising writer.

John Canemaker, in his book Winsor McCay: His Life and Art (2018), said Stanton met Winsor McCay.

In an interview in 1911 in Atlanta with a fifteen-year-old aspiring cartoonist, Frank L. Stanton, Jr., McCay discussed the problem of earning a living when starting out in “this cold, cold world.” He advised the boy that “determination is the main thing…push yourself. If you go out with the idea that you’re not going to make good, you never will.”The 1913 Atlanta city directory listed Stanton and his father at 675 Highland Avenue. In the 1915 directory, Stanton’s occupation was cartoonist.

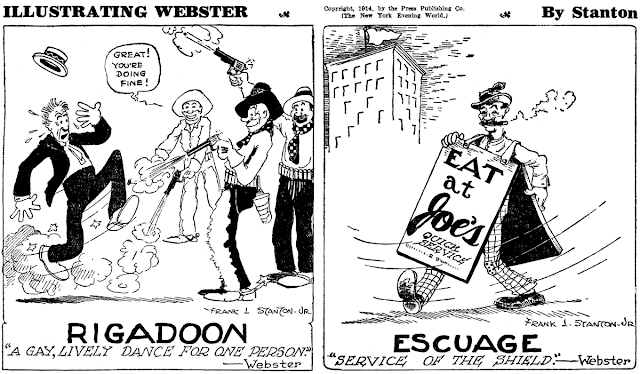

American Newspaper Comics (2012) said Stanton drew Illustrating Webster, from June 25 to October 31, 1914, for the New York World. In 1916 Stanton produced Oh, Yes for the J. Keeley Syndicate.

On June 5, 1917, Stanton signed his World War I draft card. He was promotion manager at the Atlanta Georgian. He was described as medium height and build with brown eyes and dark brown hair, and had a lame left leg.

The Editor & Publisher, August 18, 1917, covered the convention of circulation men in Atlanta and said

In the official programme, which is a work of art, and which will be preserved as a permanent souvenir of the nineteenth annual convention by its members, many attractive illustrations appear. The covers are ornamented by a clever design, the work of Frank L. Stanton, Jr., in which a watermelon figures alluringly, pictured in its native lair and in its just-so coloring of green.According to the 1920 census, Stanton lived with his parents at the same Highland Avenue address. He worked in the newspaper circulation department. The 1920 city directory listed his job as manager of the subscription department.

Stanton was a cartoonist in the 1921 city directory. The following year, Stanton’s directory listing said he was an advertising writer for the George Muse Clothing Company.

The Haberdasher, January 1922, featured several clothing advertisements including two from George Muse Clothing Company, numbers two and seven.

The Atlanta Constitution, October 20, 1925, noted Stanton’s wedding, “Society is interested in the wedding of Miss Dorothy Popham, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. J. W. Popham, and Frank L. Stanton, Jr., which will be solemnized at 8:30 o’clock this evening at the home of the bride’s parents on Peachtree road, the Rev. Father Hasson performing the ceremony.”

According to the Bulloch Times and Statesboro News, May 16, 1929, Stanton was elected to honorary membership in Pi Delta Epsilon, a journalistic fraternity; see page two, column one.

In the 1930 census Stanton lived in Atlanta at 1789 Peachtree N.W.. His house was valued at $55,000. He was an advertiser for a retail clothing store.

Fairchild’s List of Store Executives (1930) listed Stanton in two George Muse Clothing Company positions, sales manager and advertising manager.

Advertisement in 1931 Forum, Fulton High School, Atlanta

Stanton passed away January 17, 1932. The headline in the Macon Telegraph, January 18, 1932, read “Frank L. Stanton, Jr., and Wife Killed in Crash”. Their daughter survived unhurt. The Associated Press report said, in part:

…Mr. Stanton was born here, the son of the beloved Georgia poet laureate whose Mighty Lak a Rose and other poems made him internationally famous. The elder Stanton was for many years a daily contributor to the editorial columns of the Atlanta Constitution and young Frank furnished much of the “atmosphere” for his father’s noted works.The Telegraph, January 19, 1932, said Stanton and his wife were laid to rest

The younger Stanton attended the Atlanta schools and the Chicago Art institute. He returned to Atlanta to become connected with the George Muse Clothing company and was soon made advertising manager, Later he was elected a vice president.

…at West View cemetery, and the couple will be buried side by side.A photograph of Stanton and his daughter is here and here.

Investigators today said Stanton, son of the late poet laureate of Georgia, probably gave his life in an effort to save his wife. It was believed their automobile struck a bridge near Perry and caught fire in the crash. Mrs. Stanton probably was killed instantly and her husband saved himself and their five-year-old daughter, but was burned fatally in attempting to rescue his wife.

The child was not injured.

Stanton was the “sweetes’ little feller” in his father’s famous poem Mighty Lak a Rose.

—Alex Jay

Labels: Ink-Slinger Profiles

Tuesday, November 06, 2018

Obscurity of the Day: Illustrating Webster

Frank L. Stanton Jr. came to the New York World with a fun concept -- cartoons illustrating in a humorous way the definition of obscure words. The World bit and began running the panel cartoon Illustrating Webster on June 25 1914, but Stanton must have been shopping them around for awhile, because the first ones include a hand-written copyright year of 1913.

The same concept would spawn several similar features, some long-lived, later on, but Stanton's version didn't stick. It only ran on some occasional weekdays in the Evening World through October 31 1914.

Stanton only managed to sell one additional feature that I know of, and that was to the J. Keeley Syndicate of Chicago two years later. It's too bad because his cartooning style was pleasing enough, and he had a good sense of humor. Stanton stayed in the publishing game, but mostly as a publisher of little-remembered magazines.

Thanks to Cole Johnson for the sample.

Labels: Obscurities

Monday, November 05, 2018

Stripper's Guide Q & A: Sharing Old Comic Strips with the Masses

Received an interesting question from a fellow who is new to the hobby of comic strip collecting. He's working on gathering together a complete run of the Oaky Doaks daily, mostly from online sources.

Q: I was thinking of creating a free little blog with the strips I've already compiled and cleaned up; or, if it's better, uploading them to the ILoveComix archive. Is that frowned upon in the hobby though? Even if I can't find good copies, I hope to compile a full run of Oaky Doaks and hopefully bring the title out of obscurity a little for anyone who'd like to view it--but I don't want to do anything as a new guy that isn't the norm. If everyone has a pet project like this, collecting and keeping secret a run of obscure strips, I don't want to step on that I suppose.

A: First of all, my compliments on your good taste. I love Oaky Doaks, and if I had the time I'd be gathering the strip myself.

Let's start by looking at your question strictly from a legal standpoint. To create a website that offers a substantial run of any strip, the first thing you should consider is whether you will run afoul of copyright laws. Caveat emptor on what follows because I am not an attorney.

Under current law it is my understanding that anything prior to 1923 (maybe 1924 now) is always fair game. Obviously Oaky Doaks doesn't qualify. There is a rule, though, for works published from 1923 to 1963, which covers the whole run of Oaky Doaks, that copyrights must have been renewed in order to stay in force. The renewal is supposed to occur sometime in the 27th or 28th year after publication. If the copyright on the Oaky Doaks strips was not renewed, theoretically you are free to reprint them at will.There are online sources for searching these copyright renewals, but they are by no means perfect or exhaustive. Proceed with caution. A copyright attorney may be needed to perform a more definitive search.

Another option for checking copyrights is to simply ask the entity that held them. If they tell you they no longer hold that copyright, you are again free and clear. In the case of comic strips, it may be worthwhile to get that release from both the syndicator and the estate of the creator, in case the renewal that you couldn't find was in a different name than the original copyright.

Okay, now let's be realistic. Do most people jump through all these hoops to put some comic strips on a website? No. But that doesn't mean they shouldn't. And if they forgo all these checks, they should know that they are opening themselves up to a cease and desist letter, or at worst a full-blown lawsuit. It doesn't happen very often, but it can happen.

That brings us to Steve Cottle's ILoveComix archive. While I applaud the concept, I have found the interface impenetrable so that I don't really know what he's put together there. Maybe I'm just too dumb to figure out his site. Anyway, I see that he's offering subscriptions for a monthly fee, but without knowing if that gets you a better interface, or what is actually available, I just can't open my purse. I do get the feeling that he is on pretty thin ice, copyright-wise, and that makes me uncomfortable ... but I guess that's his problem, not mine.

Seems to me that if you are going to go to all the trouble of finding and restoring all these strips, you don't want to hide them behind someone else's paywall or oddball website design. You should either benefit yourself, or if your desire is just to share, do so freely and openly in a format in which fans can easily take advantage. As long as you are comfortable that the lawyers won't be nipping at your heels, go for it!

As to comic strip collectors secretly amassing fabulous runs of comic strips that they won't share, I certainly wouldn't put it that way. There are several reasons I and many other collectors don't upload massive amounts of old comic strips. First is the legal problem that we just discussed. Second, the investment of time would be substantial and I for one am too busy with the Stripper's Guide project, which has different aims than sharing long runs of strips. Third is that when a collector pays good and often substantial amounts of money for their strips, they may consider that an investment. Once most comic strips are reprinted the resale market for the original tearsheets basically goes into freefall, leaving that collector with a lot of practically worthless paper. For instance, my Li'l Abner and Little Orphan Annie daily strips, numbering in the many thousands, are almost better used as kindling for the fireplace than trying to sell them.

Q: I was thinking of creating a free little blog with the strips I've already compiled and cleaned up; or, if it's better, uploading them to the ILoveComix archive. Is that frowned upon in the hobby though? Even if I can't find good copies, I hope to compile a full run of Oaky Doaks and hopefully bring the title out of obscurity a little for anyone who'd like to view it--but I don't want to do anything as a new guy that isn't the norm. If everyone has a pet project like this, collecting and keeping secret a run of obscure strips, I don't want to step on that I suppose.

A: First of all, my compliments on your good taste. I love Oaky Doaks, and if I had the time I'd be gathering the strip myself.

Let's start by looking at your question strictly from a legal standpoint. To create a website that offers a substantial run of any strip, the first thing you should consider is whether you will run afoul of copyright laws. Caveat emptor on what follows because I am not an attorney.

Under current law it is my understanding that anything prior to 1923 (maybe 1924 now) is always fair game. Obviously Oaky Doaks doesn't qualify. There is a rule, though, for works published from 1923 to 1963, which covers the whole run of Oaky Doaks, that copyrights must have been renewed in order to stay in force. The renewal is supposed to occur sometime in the 27th or 28th year after publication. If the copyright on the Oaky Doaks strips was not renewed, theoretically you are free to reprint them at will.There are online sources for searching these copyright renewals, but they are by no means perfect or exhaustive. Proceed with caution. A copyright attorney may be needed to perform a more definitive search.

Another option for checking copyrights is to simply ask the entity that held them. If they tell you they no longer hold that copyright, you are again free and clear. In the case of comic strips, it may be worthwhile to get that release from both the syndicator and the estate of the creator, in case the renewal that you couldn't find was in a different name than the original copyright.

Okay, now let's be realistic. Do most people jump through all these hoops to put some comic strips on a website? No. But that doesn't mean they shouldn't. And if they forgo all these checks, they should know that they are opening themselves up to a cease and desist letter, or at worst a full-blown lawsuit. It doesn't happen very often, but it can happen.

That brings us to Steve Cottle's ILoveComix archive. While I applaud the concept, I have found the interface impenetrable so that I don't really know what he's put together there. Maybe I'm just too dumb to figure out his site. Anyway, I see that he's offering subscriptions for a monthly fee, but without knowing if that gets you a better interface, or what is actually available, I just can't open my purse. I do get the feeling that he is on pretty thin ice, copyright-wise, and that makes me uncomfortable ... but I guess that's his problem, not mine.

Seems to me that if you are going to go to all the trouble of finding and restoring all these strips, you don't want to hide them behind someone else's paywall or oddball website design. You should either benefit yourself, or if your desire is just to share, do so freely and openly in a format in which fans can easily take advantage. As long as you are comfortable that the lawyers won't be nipping at your heels, go for it!

As to comic strip collectors secretly amassing fabulous runs of comic strips that they won't share, I certainly wouldn't put it that way. There are several reasons I and many other collectors don't upload massive amounts of old comic strips. First is the legal problem that we just discussed. Second, the investment of time would be substantial and I for one am too busy with the Stripper's Guide project, which has different aims than sharing long runs of strips. Third is that when a collector pays good and often substantial amounts of money for their strips, they may consider that an investment. Once most comic strips are reprinted the resale market for the original tearsheets basically goes into freefall, leaving that collector with a lot of practically worthless paper. For instance, my Li'l Abner and Little Orphan Annie daily strips, numbering in the many thousands, are almost better used as kindling for the fireplace than trying to sell them.

Labels: Q and A

Comments:

Oaky Doaks, if I remember correctly, was put out in the days when the Associated Press had a cartoon division. Still they're still around and rich, that is a risk factor; compare with some of the more obscure syndicates that may have vanished decades ago, leaving little or no trace (and who probably didn't do the renewals).

The complete daily run of Oaky Doaks in currently available through the many newspapers on newspapers.com. The Sundays version is also available except for the last Sunday from 1956 because the Baltimore Sun ran the Sundays for many years.

Re: Oaky Doaks. The most recent copyright notice I can find is for 1943; no renewals (after 28 years) are listed for any Oaky strips. It is therefore public domain. The Library of Congress comes to the same conclusion ("No copyright information found with item.") on a display of one image, and so does the Digital Comics Museum, which is listing 1935-39 on their site with the disclaimer.

Re Steve Cottle's ILoveComix: As I've said many times, if you go to the correct link -- NOT the one you gave in the article -- there is no sign in required unless you want to take advantage of features that Box.com offers. Use https://ilovecomixarchive.app.box.com/v/Archive and navigation should be straight forward; and. after the first screen, there is always a download button located in the upper right

Re the I love comics site:

Yes, negotiating the menu on the site is not self evident. This link takes you into page one of the main menu:https://ilovecomixarchive.app.box.com/v/Archive/ If you want to move to page two go to the bottom of the page and click on the > arrow for page two.

Yes the letters are not in alphabetical order, to enter the sub menu double click in the letter entry line that you wish to examine under the Updated field, this may give you a further menu and you will have to click again on the sub-menu, again on the updated field. This should then present you with the files that are available. Tab or move the cursor to the three docs at the right of the menu, click on that (or hold the cursor over the dots and the message more options appears) and the message download appears. Download may start automatically or you may have to confirm the download depending on your browser. On pages where there are a number of files you wish to download if you press “control A” to select them all or select them individually using the mouse and adding others by pressing the control button at the same time. Sometimes in the sub menu there are a number of pages, and you need to move through them one page at a time.

Yes the files are not all in numerical or date order.

Yes some of the files are not in as high resolution as you might like. Still it is a valuable resource.

Regards

Post a Comment

Yes, negotiating the menu on the site is not self evident. This link takes you into page one of the main menu:https://ilovecomixarchive.app.box.com/v/Archive/ If you want to move to page two go to the bottom of the page and click on the > arrow for page two.

Yes the letters are not in alphabetical order, to enter the sub menu double click in the letter entry line that you wish to examine under the Updated field, this may give you a further menu and you will have to click again on the sub-menu, again on the updated field. This should then present you with the files that are available. Tab or move the cursor to the three docs at the right of the menu, click on that (or hold the cursor over the dots and the message more options appears) and the message download appears. Download may start automatically or you may have to confirm the download depending on your browser. On pages where there are a number of files you wish to download if you press “control A” to select them all or select them individually using the mouse and adding others by pressing the control button at the same time. Sometimes in the sub menu there are a number of pages, and you need to move through them one page at a time.

Yes the files are not all in numerical or date order.

Yes some of the files are not in as high resolution as you might like. Still it is a valuable resource.

Regards