Saturday, February 12, 2022

Herriman Saturday: March 16 1910

In the matter of the 45-round Langford - Flynn fight, Herriman was quite the flip-flopper. On the 10th he expressed grave misgivings for Flynn having the fortitude necessary. On the 14th he claimed the Flynn had set the perfect trap for Langford. Now on the 16th, the day before the fight, he's back to the opinion that Flynn is in deep trouble. But we forgive Garge for all his twists and turns of opinion because, hey, krazy-ish kat today!

Labels: Herriman's LA Examiner Cartoons

Friday, February 11, 2022

Ink-Slinger Profiles by Alex Jay: Raymond Flanagan

Mrs. Melvin Crepeau of Columbus, O., who has been visiting with her mother, Mrs. Mary Flanagan, 714 Forest av., returned Monday to her home. She was accompanied by her brother, Raymond Flanagan, who will enter the Columbus Art school for the winter.

When a Ford roadster driven by Raymond Flanagan collided with a seven-passenger Oldsmobile occupied by A.R. Briese, Charles Eagon and Walter Williams, on the South Bend Niles road yesterday all four were painfully hurt—Flanagan the worst. All live in South Bend. Only the rear wheels of the Ford are usable. The other machine was also badly damaged.

Raymond Flanagan, formerly at the head of the art department of the Lamport-MacDonald Company, advertising agency of South Bend, Ind., and Ralph Slick have opened an advertising art studio in South Bend.

Labels: Ink-Slinger Profiles

Thursday, February 10, 2022

Ink-Slinger Profiles by Alex Jay: Earl Reeder

Earl Reeder, who has been employed on the Grand Rapids Herald at Grand Rapids, Mich., arrived in this city Monday morning to spend several days visiting with his parents, Mr. and Mrs. J. W. Reeder, W. Front st. Mr. Reeder has resigned his position and will leave soon for Bloomington, Ind., where he will reenter Indiana university. Mr. Reeder was formerly connected with The News-Times.

Fred Grimes and Earl E. Reeder, of Camp Custer, Battle Creek, Mich., have arrived in the city to spend a few days furlough with their parents, Mrs. Rose F. Grimes, 119 Niles av., and Mr. and Mrs. J. H. Reeder, 315 W. Front st.

Two Former News-Times Men Will Get “Straps”Two former News-Times employees have qualified to receive commissions in the third officers’ training camps, which have just closed. Fred A. Grimes, and Earl E. Reeder, both of Mishawaka, finished their courses in training and will be given commissions as son as officers are needed.

Mishawaka Man Gets CommissionEarl E. Reeder, Former News-Times Man, Is First Lieutenant.Earl E. Reeder, son of Mr. and Mrs. J. H. Reeder, 315 Front st., has received a commission as first lieutenant in the infantry. He graduated from the officers training school at Camp Custer, Battle Creek, Mich., several weeks ago. Lieut. Reeder is now stationed at Camp Lee, Petersburg, Va.Lieut. Reeder is a well known Mishawaka young man. He was employed at the Mishawaka office of The News-Times for several years, then later at the South Bend office. He also was connected with the Grand Rapids Herald. He is a graduate of the Mishawaka high school. He attended Notre Dame university, and graduated from Indiana university.

Honorably DischargedLieut. Earl E. Reeder, of the 78th infantry, has received his honorable discharge. He is at present visiting his parents, Mr. and Mrs. J. H. Reeder, Fisher court. Lieut. Reeder was formerly connected with The News-Times.

Miss Madge Grant, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. D. A. Grant of South Bend, and Earl E. Reeder of Mishawaka were married at 4 o’clock Saturday afternoon by Rev. R. Everett Carr of Kankakee, former vicar of St. James Episcopal church of South Bend. Mr. Reeder is a member of the advertising firm of DeLeury & Reeder of South Bend and his bride was formerly employed on the editorial staff of the South Bend Tribune.

Labels: Ink-Slinger Profiles

Wednesday, February 09, 2022

Obscurity of the Day: Deb's Diary

Previously a long-standing resident of our Mystery Strips list, Ray Bottorff Jr. sleuthed out this feature for us. Thanks Ray! Deb's Diary is a rather text-heavy feature for inclusion in our ranks, but the referee is feeling magnanimous today, so in it goes.

The feature debuted on March 21 1927*, sporting art by Raymond Flanagan and text by Earl Reeder, and distributed by the John F. Dille Company. The idea was a twist on the flapper panels so popular in the 1920s. Instead of a pithy little one-liner from a beautiful young thing, Deb's Diary would offer readers somewhat lengthy entries from her diary.

The feature didn't really click with readers, probably because it was a substantial amount of reading they were expected to do in order to get to relatively weak gags. In other words, the pay just wasn't commensurate with the job.

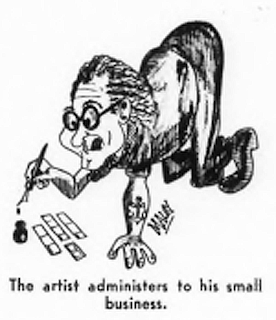

Raymond Flanagan, a very good cartoonist/illustrator, didn't help things much. He seemed to think of his panels as mere window-dressing; no attempt was made to contribute to the humour of the feature.

With an already slim client list getting slimmer with every week, the creators and Dille decided that something needed to change. On December 19, after what seems to have been a one week hiatus, the feature was changed into a humorous take-off on advice columns. Deb would now supply funny answers to romantic conundrums.

This new direction, I think, was a good one. Reeder seemed to be able to get off better gags more frequently. Unfortunately he was still wordy, and Flanagan still seemed to feel no compunction to add to the hilarity. The Harrisburg Telegraph finally dumped the feature on March 3 1928. Since the feature was listed in the Editor & Publisher listings for 1928, though, it was possibly still limping along in August of that year, when the Syndicate Directory is published.

Reeder hung onto the feature like a bulldog. Although I am unable to find a single example anywhere, in the 1931 Syndicate Directory Deb's Diary appears once again, this time as a daily 500 word column, sans illustration, also syndicated by Dille.

* Source: All dates from Harrisburg Telegraph

Labels: Obscurities

Tuesday, February 08, 2022

News of Yore 1969: John Henry Rouson Profiled

Former Commando Cartoonist now Fights Daily Deadlines

by Don Maley (Editor & Publisher, June 14 1969)

John Henry Rouson draws big laughs with four mini-cartoons he grinds out for General Features Syndicate. Rouson, a transplanted Englishman, says he learned to draw small during World War II when newsprint was scarce on Fleet Street and consequently newspaper art shrunk.

The four cartoons Rouson draws 24-times-a-week are: Boy and Girl, Ladies’ Day, Little Sport and Little Eve. Collectively they appear in 300 papers,according to the syndicate. As an example of the Liliputian size of Rouson’s work both the Little Sport and Little Eve panels are drawn on 1” by 7” inch panels. “All European artists have to draw small,” says Rouson, “in Europe space is valuable.”

His Boy and Girl feature was originally four panel but has been cut down to one column “but could be run in two.” Ladies’ Day is a six-a-week spot designed for distaff sports buffs. Although all four features rate high marks in the humor department. Their creator has a background that reads like something written by Ian Fleming — one of Rouson’s wartime buddies—and is chock-full of adventure, rather than fun.

The 60-year-old artist began drawing comic strips in the very early 30’s “Once I got started,” he says, “things happened quickly.” Quickly indeed. In his heyday in England young Rouson scratched his by-line on to six features: Shop Acts (“Life in a general store . . . six - a - week.”). Our Gracie (“Done with Gracie Fields six times a week.”) Little Sport (“Only once a week then.”), Boy and Girl (“Originally called Boy Meets Girl done once-a-week for the London Sunday Dispatch.”), Theatrical Caricatures for the London Bystander and gag cartoons for Punch.

“I wasn’t making too much money back in those days,” says Rouson, “only about $300 a week.” To supplement his income he appeared on British television drawing cartoons. “We had telly in England back in 1938 and ’39—it was very primitive,” he says. He also drew cartoons and wrote reviews for Modem Motoring, the Roots Motors monthly magazine.

Sporting Publisher

“Another fellow and I started a paper called the Sporting Record,” he says of another venture, “and we ran it for about two years. We bought it very cheaply and eventually built up a circulation of 14,000. We were all set to go into the football season when the war came along and killed it for us. We sold out to a publisher who was looking for a publication that would be a good source of newsprint for his other publications. He built it up however and sold it for a fat quarter-of-a-million. I got back the $20,000 I put into it.”

During the nine years that Rouson expended creative energy all over the British Isles he thrived. “It all sounds like an awful lot of work but it wasn’t really. Everything dovetailed together. I loved both sports and the theatre and I’ve always liked cartooning. I did the strips during the day and the rest of the work at night. It was wonderful in a way, I was in my 20’s then and was young and enthusiastic and found the work relaxing. But by the time the war came around I started to sag.”

Rouson joined the Royal Navy in September, 1939, three days before England went to war against the Axis powers. “I joined the Patrol Service,” he says, “and was assigned to a 46-foot yacht I had sailed before. We were at Dunkirk and were assigned to traffic duty, directing small boats in and out of the beach. The original crew of four grew to six and they promoted me to second in command. We ended up patrolling the Thames doing routine naval drudgery.”

Rouson hates drudgery and as fate would have it the sophisticated cartoonist who joined the Navy as an ordinary seaman (the lowest of the low in the Naval chain of command) was discharged seven years later as a Lieutenant Commander, O. B. E., G. M. The last two letters stand for George Medal, one of Great Britain’s highest military decorations. He succeeded in the Navy by joining an elite group of sailors who seemed hell-bent on committing suicide.

Because of his poor eyesight, the bespectacled Rouson knew he’d never see action more exciting than chasing skinny-dippers out of the Thames, so he volunteered for special assignments as a weapons defuser. “I thought I might have a go at it,” says Rouson Britishly. “It was a little rugged at first. Some of the devices we used in the early months of the war were, now that I think of it, rather laughable. (Sledge hammers and such.) We worked in teams—one officer, one sailor as a rule—and we lost a lot of men at the beginning, but the losses tailed off as we picked up greater experience.

Three Survive

“Of my original 12 man crew I guess only about three came through. Many of the volunteers were fellows who, like myself, had poor eyesight, or other slight physical impairments.” (A close look above Rouson’s horn-rims divulges a scar on the right side of his forehead—a permanent reminder that war is far from hilarious.)

During the early years of thewar, when the Germans were ‘blitzing’ England, Rouson and his crew were kept busy defusing large, magnetic naval mines the Germans parachuted from airplanes.

“At first the Germans dropped them into the sea,” he says, “but they made such a loud noise, scaring the pants off of everybody within earshot, that they switched tactics and started dropping them on land targets. These naval mines were dropped in large numbers during the ‘blitz’ attacks on Coventry and Glasgow. At Glasgow, when we were sent up after a raid, we found about 90 such mines that had been dropped all over the place, and, as was often the case, about one out of every three — in this instance about 30—failed to explode.”

In an attempt to booby-trap the mines, the Germans attached a 14-second timing device designed to blow up anyone attempting to take them apart. Once, Rouson recalls, there was an eight-second count on a mine which he was dismantling.

Rouson’s initial instructions for his dangerous assignment took one entire afternoon. “learned on the job,” he says. “A guy was killed the first day. We didn’t know anything about theory and were quite a group. There were playboys, teachers, businessmen and we even had a hunting secretary with us.” Later Rouson learned how to dive—for undersea work. On an island “south of Singapore,” he found one of the first Japanese mines ever recovered by the Allies. He was on the last English ship to leave Singapore before it fell to the Japanese.

Later he took the first acoustic torpedo out of a German sub—“in the Mediterranean off the French port of Toulon.”

Meets Ian Fleming

It was during this period that Rouson met Ian Fleming when his “Rendering Safe Party” became a “Commando Assault Unit,” and they worked closely with British Intelligence, to which Fleming was assigned.

One expedition Rouson vividly remembers was when six little Japanese two-man subs penetrated the submarine nets at Sydney, Australia, and sneaked into the harbor. “These little subs,” says Rouson, “probably came from a larger sub, got through the Sydney nets at night and created all kinds of confusion.” Rouson and his crew dived for, and reclaimed wreckage from five-and-a-half of them.

Rouson came back from the war with his Boy and Girl strip, which he drew all over the world and mailed to the London Dispatch from wherever his Navy assignments took him. He also returned with tattoed arms. “I got these,” he says of the tattooes, “in Singapore. Over there the Malay sailors respect tattooed officers and all of the British officers stationed there had tattooes, from the Admiral on down.” One of Rouson’s tattooes is a map of England inscribed in Chinese.

Rouson’s experience in the explosives field prompted the U. S. Navy to request his transfer here in 1944 to lecture on his activities to naval personnel. While here he decided that the U. S. was the best place, at war’s end, for him to further his career as a professional cartoonist. “I realized,” he says, “that if I was going to stay with cartooning my future would be in the States.” He had originally visited the U. S. briefly in 1939 and found then that American cartooning markets far surpassed those in England.

Before migrating to the States Rouson found himself at loose ends. “I had just gotten out of the Navy and had found the war to be very exciting. I just couldn’t visualize sitting at a drawing board for the rest of my life.”

Rug Fiasco

So he went to India with another recently-sprung member of his crew. “We bought a warehouse-full of Indian carpets there,” he says, “and had visions of making a fortune exporting them. But we couldn’t get an export license and had to get rid of them.”

Next the war hero — who wanted to be a jockey as a youth—placed an ad in a London paper which read: “Will go anywhere, do anything.” But no one wanted him to go anywhere, or do anything.

Then he went to Paris where he studied and painted steadily for two years before coming to the States.

“When I came here, in 1948, my first interview for a job was with the New York Herald-Tribune,” he says. “I applied for a spot as a theatre caricaturist and they sent me out on an assignment the same day of the interview — to Philadelphia. ‘Oh boy!,’ I thought, ‘This is how they do business in the States’.” Rouson can’t remember the name of the play he was sent to see in Philadelphia, but he does remember the stars: Melvin Douglas and Jan Sterling. “Miss Sterling had a broken nose,” he remembers, “and I noticed that it’s since been changed.”

Rouson stayed with the Herald-Trib until later that year when he Americanized Little Sport, the gag-a-day adventures of a harried, hapless little silent practitioner of many sports who usually seems to be on the losing end (when he rode to hounds, a fox chased thedogs).

Limited Budget

“I only brought $1,000 with me,” he says, “and my budget was extremely limited. I needed an income badly so I showed the strip to a few syndicates but they turned it down. The shape of the strip and everything else about it was so new that nobody thought it had a chance. One night at a cocktail party I met someone who told me I might try the Philadelphia Bulletin. I went there the following day but they too turned down the strip. They could see no hope for it and said it was the wrong shape and full of English humor. I showed it to a reporter who liked it and he told me to try the Philadelphia Inquirer. Eventually they bought it and ran it in the Inquirer and in the Morning Telegraph, another Annenberg paper. Later we syndicated it with George Little of General Features and within a few months we were in 70 papers.”

That was in February, 1949. In October, 1955 Rouson Americanized Boy and Girl, aided and abetted by George Little. Little Eve first saw the light of day in January of 1954 and was drawn by his ex-wife Jolita. Although divorced, Rouson continues to draw the strip under Jolita’s by-line. Ladies Day came into being December, 1958.

Horsey Artist

Little Sport started out as a racing feature, but in order to gain a more universal appeal Rouson switched his attention to all sports. “It’s simply an attempt to satisfy everybody from the major sports on down to horseshoe pitching and weightlifting. Racing, however, continues as my favorite sport. Baseball? The sport seems to have some wonderful personalities, but it still seems like ‘rounders’ to me.”

“I get some funny mail on that Little Sport,” says Rouson, for 17 years a resident of New York’s Staten Island, “a lot of people think there’s a code someplace in the strip that gives the numbers of winning racehorses. I don’t know how people see these things in the strip, the only code I use is a numerical one for the date.”

The self-taught artist is much sought-after by racehorse owners. “I do a lot of horse portraits by commission only,” he says, “and many of them have appeared in Turf magazine. I’ve travelled all over the U.S. and Canada doing horse portraits and love doing it. I’d like to do it full-time, but I have my strips and although it sometimes gets tedious doing four strips a week I like doing them too.’’

He finds painting to be a form of therapy. “Besides thoroughbreds,” he says, “I have a great appreciation for color . . . it’s such a welcome change to be able to use color after the daily routine of black and white in newspaper work.”

The son of a butcher (“It’s a paradox, he loved animals.”) Rouson is a life-long horse buff. “An uncle of mine,” he says, “was a carriage builder to the Royal Family and he owned some trotters. One of my biggest thrills as a kid was when he let me hold the horse’s reins. And I was always reading Sporting Sketches magazine, it was full of beautiful sketches of jockeys and horses.”

“I sometimes wish,” he says, gazing out at the view of New York Harbor he can see from his patio, “that I could devote all of my energy into just one strip. With income tax the way it is I could comfortably drop a strip or two and get along just great, but my contract won’t allow me to do so.”

The former theatre critic says he has “no enthusiasm for writing anymore.” He even hates to answer his mail. “Cartooning,” he concludes, “has become a way of life with me. It used to be an adventure, but no more. I’m at an age now where I feel that my next big adventure will be retirement.

Labels: News of Yore

Monday, February 07, 2022

Obscurity of the Day: Boy and Girl

John Henry Rouson was a newspaper cartooning specialist. His specialty was tiny features that could be shoehorned into various sections of the newspaper, not just the comics page, and he could turn them out in wholesale quantities. He had four long-running daily features running concurrently, two of which he created under pseudonyms so as not to appear too ubiquitous for his own good.

Boy and Girl was the third of these mini-features, all of which were syndicated by General Features. General was no powerhouse in the sales department, but between the four features Rouson would claim to a total of 300 papers in his client list. Less than a hundred papers per feature is not a particularly impressive number, but in the low-rent world of General Features Rouson must have been considered a house superstar.

Boy Meets Girl debuted on October 3 1955*, really just an Americanization of a feature he had previously penned for the London Dispatch in the 1940s. It was a two panel strip that chronicled the world of romance. For Rouson this most often translated to strips about the comedic aspects of boys pursuing girls. The title was changed to Boy and Girl just a few months after it debuted, probably because the title was already copyrighted by someone else.

The tiny feature offered simple mostly pantomime gags that could be digested in a second or two, It ran for many years yet is little remembered, as are all of Rouson's features, because they were rather generic gags with no continuing characters.

At the end of 1974 General Features sold its contracts off to the Los Angeles Times Syndicate. Some of General's features were given the ax, but Rouson's were continued by the new syndicate. However, given that Rouson was now pushing 70 and that the LA Times didn't seem to be out there really hawking his material, Rouson started cutting back. Boy And Girl was the second of his features to be retired, last running on December 27 1975**.

Rouson had a very interesting life; I highly recommend the News of Yore profile of him that will appear as our next post.

* Source: New York Daily News

** Source: Bridgeport Post

Labels: Obscurities

Sunday, February 06, 2022

Wish You Were Here, from Charles Schulz

Linus utters one of his catchphrases on this way-too-groovy-for-the-1980s postcards. This Hallmark card, unlike most in my collection, bears no ID code on the back.

Labels: Wish You Were Here